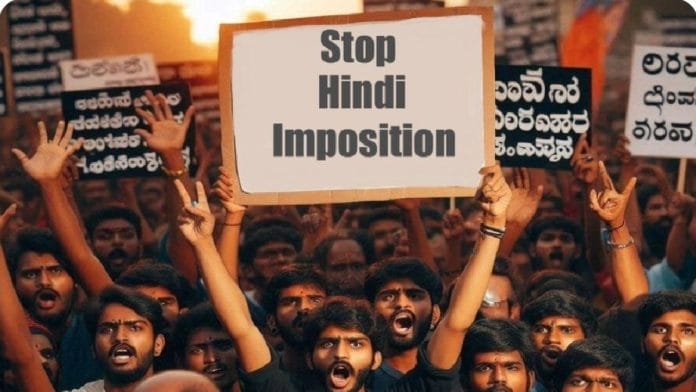

Bengaluru: Kannada versus Hindi. Outsiders versus Kannadigas. North versus South. The tension over language and identity in Karnataka is spilling from the digital realm onto the streets of Bengaluru.

In the last three weeks, there have been at least three clashes between service providers and customers.

“You outsiders come here, speak in Hindi and English…in Karnataka, speak only Kannada,” said an autorickshaw driver during an altercation with a 23-year-old visual merchandising professional and her friend from Kerala. Last month, an auto driver was arrested for allegedly slapping a woman for cancelling a ride. On 30 September, a 52-year-old owner of a tent renting company from Tumakuru was assaulted by staff after he asked them to learn Kannada when they couldn’t understand what he meant by ‘deepada kamba’, which means lampstand in Kannada.

These instances point to the growing ‘language militancy’ in India’s IT capital, where a section of people are violating laws, discriminating against, or denying services to people on either side of the pro-Kannada and pro-Hindi debate. In most cases, the clashes occur between auto drivers and customers, but even disputes over fares and cancellations take on a linguistic dimension.

Over the past few months, whether due to the celebration of Hindi Diwas or rising tensions between pro-Kannada groups and ‘outsiders’, the issue has gained traction among a growing army of ‘digital guardians’ who oppose the necessity of learning Kannada while in Karnataka. Much of the recent attention on Bengaluru is also due to Chief Minister Siddaramaiah’s vocal opposition to the imposition of Hindi by the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government.

Similar tensions also play out in cities like Mumbai and Chennai. But Bengaluru continues to attract significant attention over this issue, with at least 40 percent of the city’s population comprising migrants. This cosmopolitan culture is often cited as a reason for the lack of obligation to learn Kannada.

“We don’t categorise offences based on language,” said Bengaluru city police commissioner B Dayananda.

The case involving Rafieq was classified under assault and breach of peace. The auto driver who slapped a woman was booked under Sections 74 (intent to outrage the modesty of a woman) and 352 (provoking breach of peace) of the BNS. In the case of the two women from Kerala, a complaint filed with the cab aggregator did not elicit any response.

“I don’t agree with such attacks, nor is linguistic hegemony the solution. Multilingualism is the basic feature of Indian society, and you have to sustain it,” said Purushottama Bilimale, chairman of the Kannada Development Authority (KDA).

Not everyone shares this view. Manjunath, president of the Adarsha Auto Union, pointed out that most clashes occur between drivers and passengers.

“When some people don’t know Kannada and in that fight have misunderstood what the auto driver is saying, they post it on social media as harassment and discrimination against outsiders. Most videos are posted without context and project the entire auto driver fraternity in a poor light,” he said.

Also read: Digital guardians of Kannada are waging a new language war in Karnataka against Hindi imposition

‘Kannada not a hegemonic language’

Sugandh Sharma, an influencer with around 17,000 followers on Instagram, attracted significant attention for her videos claiming that Bengaluru would become empty if North Indians left. The video, posted late on 23 September, went viral but also drew criticisms and even a police complaint. Days later, she posted another video apologising for hurting sentiments.

The number of videos, blogs, and posts playing on a loop on social media creates the impression that this issue is the only thing that matters in Bengaluru.

Historians say that while tensions have always existed, the nature of these exchanges has changed.

“Bengaluru has always been the site of tensions around language, and one could even say, it has long been the only site of aggressive Kannada assertion since it is a dominant language in the public sphere,” Janki Nair, author and historian, told ThePrint. She added that Kannada “has simply not crossed over to being a hegemonic language” and has relied too heavily on the state for its assertion. She said that Kannada was first edged out by Tamil, then English, and now Hindi has been asserting itself.

Language militancy has reached a point where Kannadigas are calling out pro-Kannada groups for discriminating against counterparts in northern and coastal Karnataka, where the dialects differ. Tulu speakers have accused mainstream pro-Kannada groups of appropriating ‘Tulunadu’ culture.

People from North Karnataka are often targeted by online factions when they seek more focus from the administration. One user on the platform X, @Uttarakarnataka3, noted that politicians primarily aim to attract investments and projects to Bengaluru, often ignoring the rest of the state.

“There is a cultural aspect also; since Bangalore is in the south of Karnataka, our culture and language are ignored,” the user told ThePrint.

Also read: A new language war in Karnataka is brewing. This time over Tulu dignity

‘Kannada as business language’

The Karnataka government, led by Chief Minister Siddaramaiah, has been pro-Kannada and against the imposition of Hindi. His policies—at least on paper—reflect this stance.

“All the people living here are Kannadigas. No matter what your language at home is, the business language should be in Kannada,” Siddaramaiah said in Raichur, speaking at an event marking 50 years since the naming of the erstwhile Mysore state as Karnataka.

The BJP’s online support base has been trying to amplify instances of crime, religious intolerance, or any untoward incident in Karnataka as reflections of the Siddaramaiah government’s failures. In April, Union Home Minister Amit Shah claimed that the Congress government in Karnataka had emboldened radical elements in the state. State BJP leaders have toed this line.

On Thursday, the state cabinet withdrew 43 cases against pro-Kannada groups and others booked under various provisions over Cauvery water protests and other agitations.

Even the proposal to bifurcate the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) into at least five corporations has been, as areas with larger migrant populations could lead to ‘non-Kannadiga mayors.’

While the Congress under Siddaramaiah has renewed its commitment to the Kannada platform, the BJP is also cautious not to be caught on the wrong side of the language row. The discourse surrounding Hindi’s status as a link language or its promotion predates the Modi government, but its current assertion under the ‘national language’ debate has increased the tensions.

On 15 September, the Karnataka Rakshana Vedike (KRV) and other pro-Kannada groups protested in Bengaluru, demanding that all 22 languages in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution be recognised as languages of administration. There have been several incidents across Karnataka, including from banks, where services were denied to Kannada speakers. An undated video from Kolar surfaced online in early September, showing a bank manager telling a customer to seek services elsewhere if he did not know Hindi.

With Karnataka Rajyotsava approaching on 1 November, there are fears that tensions will only intensify. Small businesses worry that pro-Kannada groups will demand higher donations for celebrating the event.

“Every year, they ask for more money. We do not bargain since we have to live and work here,” said a Malayali bakery owner near BEML, requesting anonymity.

‘Kannada classes for non-Kannada speakers’

Much of the criticism from non-Kannadiga speakers revolves around the lack of infrastructure to learn the language. In response, the KDA has implemented a programme to teach Kannada to migrants last month.

“If 30 non-Kannadigas request the KDA, we will provide trained teachers to teach Kannada to that section. This is not to teach them how to read or write like our great poets like Pampa, Ranna…but give them training in colloquial speaking for daily transactions,” KDA chairman Bilimale said.

He added that the idea is to make learning the language “simple and enjoyable’, but he conceded that there is currently no proper website or infrastructure for learning Kannada.

“When only outsiders come in, the local culture gets dismantled. If you allow this, there will be a cultural crisis, which is a greater danger to local and minor languages,” he said.

Initiatives like this could help transform animosity into opportunities for cultural exchange.

(Edited by Prashant)

Sad to see the country torn apart by language.

Also, lowkey amused by the hypocrisy of native Hindi being an imposition but foreign Turushka-speak Urdu being welcome – and, in Karnataka’s case – mandatory for Anganwadi workers [1].

[1] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/karnataka-minister-defends-recruitment-of-urdu-speakers-to-anganwadis/article68684514.ece

Modi should encourage tamil as national language instead of Hindi. Ask North to adopt to south indian languages since he expects always the south to adopt to north. Regional Diveristy is the greatest threat to national unity as per Modis ideology so they push for one language, one culture amd one religion.