Hyderabad: India’s proudest scientific legacies were never just about discovery. They were shaped by empire, nationalism, global rivalry and, later, markets. Through India’s space and vaccine stories, a panel at the History Literature Festival in Hyderabad dismantled the myth of science as apolitical.

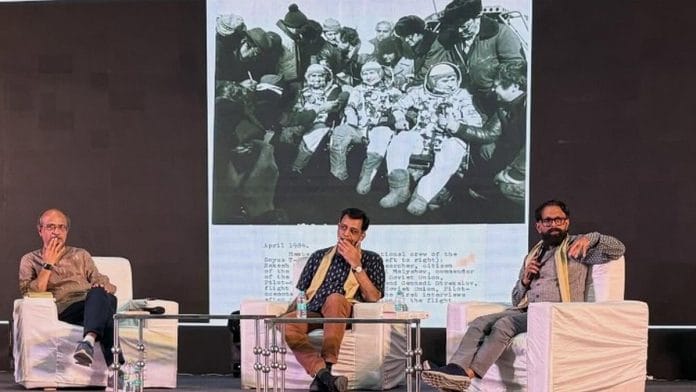

“The history of science has a lot to do with how science is done — the social factors, political factors, policy environment that shape science and technology,” said author Dinesh C Sharma at a panel discussion on Sunday, titled ‘Microbes to space probes: India’s story of science’. He was joined by environmentalist and author Ameer Shahul, with Aparajith Ramnath, associate professor at Ahmedabad University’s School of Arts and Sciences, moderating. As the panellists discussed decades of scientific achievement, the common strand was how Indian science moved with political currents rather than above them.

In a hall packed with students, researchers, and history enthusiasts, Ramnath opened by challenging the popular perception of science as “divorced from political concerns” or “only concerned with truth and objectivity.” The speakers then grounded this contention in history.

Each panellist focused on their terrain of expertise. Sharma, whose latest book is Space: The India Story, said space research grew in the shadow of the Cold War, where international cooperation and rivalry existed side by side.

On vaccines, Shahul, author of Vaccine Nation, argued that the British Empire was a big part of the story, as was liberalisation.

Also Read: Satellite imagery is redrawing India’s archaeological map

India’s space pace

Sharma traced India’s space journey to the pre-independence era.

“We have to go back to 1938 when the National Planning Committee was formed by Subhash Chandra Bose,” he said. Even before space or atomic energy were established disciplines, noted Sharma, this committee provided a blueprint for using science to solve resource shortages.

By the 1940s, scientists such as Homi Bhabha, C V Raman, and Vikram Sarabhai were already leveraging India’s geographical position near the magnetic equator to study cosmic radiation.

“Cosmic ray physics became a very important area of research in India,” added Sharma. Thumba, a fisher village in Kerala, where India’s first equatorial rocket station came up, was “a nice combination of science, history, and geography”.

But the greatest sense of urgency came with the Cold War.

“It played a key role in the direction the Indian space program took,” Sharma said. Space research operated under the Department of Atomic Energy until 1969, and international cooperation was central. Engineers were sent to NASA for training, and Thumba became a UN-linked facility where scientists from multiple countries, including France, worked together. India’s first satellite, Aryabhata, eventually launched aboard a Soviet rocket in 1975.

Sharma also drew attention to a famous image of ISRO staffers pushing along the nose cone of a rocket on a bicycle. This, he argued, did not reflect backwardness but a “creative way of overcoming resource constraint”.

That frugality became philosophy, extending even to modern low-cost missions such as Mangalyaan.

“Frugality is built into the way they do things. You have to maximise whatever is available and also do it in a fashion that is cost effective,” said Sharma.

He outlined the four pillars of India’s space programme that Sarabhai envisioned in 1970, just a year before his death: rockets, satellites, payloads, and ground systems.

Stressing that applications, from communication to remote sensing, were always the goal, Sharma paraphrased what Sarabhai had said about those questioning the relevance of space activities in a developing nation: “We don’t want to join the space race, but want to use space for our own benefit.”

Also Read: When did Kakatiya queen Rudramadevi die? Answer was under a stone pillar in Telangana

The vaccine saga

The conversation then pivoted to vaccines, including who built labs, who controlled them, and who paid. That story began in Bombay, in the middle of the 1890s bubonic plague outbreak.

“Empire is a big part of this story,” said Shahul, launching into the arrival of scientist Waldemar Haffkine at the invitation of British officials. Haffkine developed the first effective plague vaccine in a makeshift laboratory at Grant Medical College. He later conducted early vaccine trials on prisoners in Byculla.

The original ‘Plague Research Laboratory’ became the Haffkine Institute in 1925. This was also the year when Indians started playing a major role in its development, with Major Sahib Singh Sokhey taking over as its assistant director.

After becoming director in 1932, Sokhey expanded its scope considerably over the years. He set up an entomology department in 1938, followed by a serum department in 1940 to produce vaccines, antitoxins and snake antivenin. The same year, a chemotherapy department was launched to research sulfa drugs and synthetic pharmaceuticals. A pharmacology department came up in 1943, and a nutrition department was added in 1944.

“Sokhey was a hardcore nationalist. He converted [the Haffkine Institute] into a much stronger research institute. He developed and refined some of the earliest vaccines of Haffkine, and mass produced them to meet the requirements of the country,” said Shahul.

This work laid the groundwork for the post-Independence public health system.

In 1953-54, Sokhey obtained Soviet assistance to build a public-sector pharmaceutical plant to produce antibiotics and synthetic drugs in India. This later became Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Limited (IDPL), with plants in Rishikesh, Gurgaon, and Hyderabad. By the 1970s, this institutional base allowed vaccine research and manufacturing to flourish.

“The ecosystem for vaccine manufacturing and vaccine development took strong roots in Hyderabad then,” Shahul said.

He criticised the dismantling of this public-sector foundation in the 2000s. Referring to the tenure of then-health minister Anbumani Ramadoss, he noted the government “succeeded in shutting down the public sector vaccine units at a time when doses were being supplied to the government at very low cost.”

In the post-liberalisation era, the focus shifted to private enterprise.

“The real race for patenting started around that period. Vaccines became a business for profiteering by private enterprises,” he said. “For the average Indian citizen, it has become expensive.”

He noted that this led to the creation of the “big pharma” landscape in India as well.

Moderator Ramnath then gave a sobering reminder of the inescapable link between the laboratory and the state.

“You don’t have huge scientific projects without a political context, without lobbying of various kinds, and for good or for bad,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)