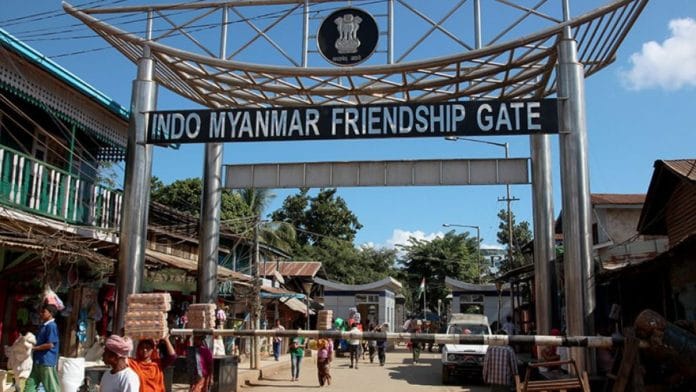

New Delhi: In a scene from Amazon Prime’s The Family Man season 3, Srikant Tiwari, played by Manoj Bajpayee and JK by Sharib Hashmi, meet Michael, played by Vijay Sethupathi—the protagonist from another hit OTT show, Farzi. Sethupathi is a Tamil cop, and the scene is set in the border town of Manipur’s Moreh.

The trio enter a small hotel run by a local Tamilian. The place has pictures of film stars, and the menu could be seen written in Tamil on its walls. “How come there are so many Tamilians in Moreh,” says a befuddled JK, asking an important question about the group’s turbulent history. Beyond all that is fictitious in the series, Moreh’s Tamil connection is a strand of actual history.

It began when Rangoon, now Yangon, situated between India and China, was one of the most important trading centres in Asia. It attracted crowds of traders and a workforce from across the continent. After the fall of Burma at the hands of the British forces in the third Anglo-Burmese war of 1885, the country became a part of British India. In 1937, Burma was separated from British India and became a separate Crown Colony, a status that lasted until it gained independence in 1948.

That’s when the British East India Company took with them both businessmen and labourers to the city. They included Tamilians, Bengalis, Telugus, and Punjabis. The British later withdrew, but the Indians remained, set up businesses and became integral catalysts of the Burmese economy.

Things changed in the 1960s, when the Burmese Military Junta took over the country, led by General Ne Win in Burma. The Enterprise Nationalization Law, passed by the Revolutionary Council in 1963, nationalised all major industries, including import-export trade, rice, banking, mining, teak and rubber. The Indian government was then asked to withdraw its diaspora from their lands.

In 1965, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri sent the first batch of ships to Rangoon. The Indian diaspora, comprising a sizable Tamilian population, headed back to India.

Setting up a new home

The refugee camps set up for the returnees had their own set of issues, and felt foreign to those who had spent their entire life in Burma. They decided to head back to Myanmar on foot, and those who undertook the journey walked through Moreh—a well-known route that led to Burma.

But at the border, they were sent back to India.

The refugees then decided to wait in Moreh, a small settlement of Meiteis and Kukis, while they hoped to someday get back to Burma. They did not go back to either Tamil Nadu or Burma, and instead set up businesses in Moreh.

Following the settlement of Tamil people, the elders of the community set up the Familial National Welfare Association to provide a space for people to meet and discuss the problems and needs and also to provide education to their children. After a few years, ‘national’ was dropped and it became the Tamilian Welfare Association.

Moreh now has the Sree Angala Parameshwari, along with the Sree Muneeswarar Temple, Sree Veeramma Kali Temple, Sree Badrakaali Temple and Sree Periyapalayathamman Temple. The Tamil Muslims built the Tamir-E-Millath Jamia Masjid, and the Catholics have built the St George Church in Moreh.

Also read: What are Amur falcons? Migratory birds with an incredible journey once hunted in Nagaland

What’s happening now

Over the years, the community has become instrumental in Moreh’s economic growth. The Moreh Chamber of Commerce controls the trade here and is headed by the president of the Tamil Sangam.

In 2023, when violent clashes between the Meteis and Kukis broke out, even the Tamil families of the region were affected. With curfews in place, trade halted, and life came to a standstill for the businesses in the town. Forty-five Tamil shops and houses were also burnt during the conflict.

Militants even asked the Tamil residents to pay ‘tax’ to them.

This was a repeat of the 90s, when they were asked to pay taxes, and many left the region, and the members of the community shrank to 3,500.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)

Fascinating story. Excellent reporting.