A girl from a respectable family is the biggest fraud in India. Manju Mai, a character in Kiran Rao’s latest film, Laapataa Ladies, declares this while frying bread pakodas. Mai, played by Chhaya Kadam, is not an urbane city woman well-versed in feminist terminology. She runs a tea stall at a railway station in a fictional Indian village.

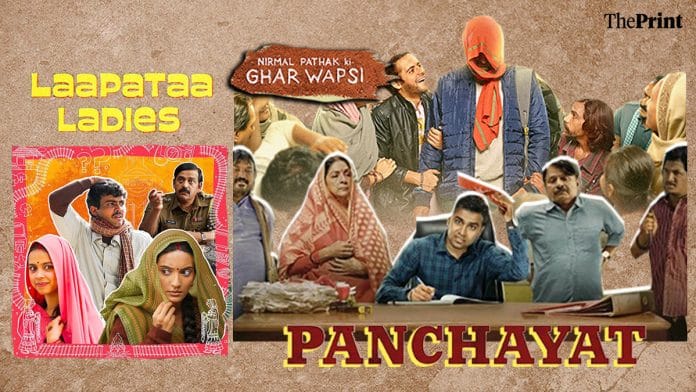

From Rao’s quiet feminism in Laapataa Ladies to the third season of TVF’s smash hit Panchayat, a nostalgia-infused Indian rural landscape has found a firm footing in the world of OTT viewership. In Laapataa Ladies, the village is a backdrop for a quiet revolution. “Women can farm and cook. We can give birth to children and raise them. If you think about it, women don’t need men at all,” says Mai.

If small town-based shows like Netflix’s Jamtara and Amazon Prime Video’s Mirzapur took audiences to India’s heartland, shows like Panchayat and Nirmal Pathak Ki Ghar Wapsi have moved deeper into villages. And they’re proving to be a success. Laapataa Ladies clocked in 13.8 million views on Netflix since it was released on 1 March 2024 beating Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Animal (2023).

The depiction of village life on streaming platforms and even on the big screen falls between the Gandhian view of the countryside being a near-idyllic space, and BR Ambedkar’s criticism of rural India’s caste biases and violence. And while Satyajit Ray’s exploration of village life through Pather Panchali (1955) remains the template, there are distinct changes in the latest iterations.

Now, villages are straddling smartphones, Instagram reels, and technology with traditional values. It informs caste politics and even local governance. Film directors are peeling these layers.

“It is actually the coming in of villagers, not village, to the screen, with a variety of languages. Be it Bhojpuri or Maithili. They are not afraid of speaking their own language,” said sociologist and psychologist Ashis Nandy.

The success of the first season of Panchayat in 2020 set the stage for villages to make a comeback. Engineering graduate Abhishek Tripathi’s struggle to adapt in Phulera, a village in north India, had the audience in splits. Now, directors, producers and streaming platforms are scouring the hinterlands to cater to the increasing allure of the beating heart of India—its villages.

“It was my mother who saw Panchayat and called me up,” said Rahul Pandey, writer and director of the Sony Liv Web series, Nirmal Pathak Ki Ghar Wapsi.

Film Companion called it a “more progressive Panchayat with a strain of dignified melodrama”. But when his mother called to tell him about Panchayat, Pandey was yet to find a producer for his story about a man who returns to his village. “Once it was pitched, within six months everything was done, and my feature film idea became the web series Nirmal Pathak Ki Ghar Wapsi,” he said.

Also read: Bollywood boomers never had it so good. Scripts making Neena Gupta, Shabana Azmi young

Beyond the exotic

In Nirmal Pathak ki Ghar Wapsi, the romanticisation is peeled away by the third episode. It begins with joy and nostalgia, as Nirmal, who has been raised in Delhi returns home to his paternal village in Bihar, but this is slowly dismantled to reveal caste politics, untouchability and patriarchy.

Initially, Nirmal (Vaibhav Tatwawadi) is a ‘tourist’ returning to his village. He chooses to travel by train because “it’s all about the experience”. He later video-calls his mother to show her the lush fields on the outskirts of his village. Everything is exotic, romantic.

The show’s intent on not being a ‘slice of life’ comes out clearly. In one scene, a character points to a statue of Ambedkar in the background while talking about his efforts to empower villagers. In another, the telltale sign of discrimination is shown when tea is served in different cups, based on one’s caste.

“The show is based on my experience of going to my paternal village. I realised how it is a big deal to be able to call someone from an upper caste a friend, or how people would actually come to see the ‘new’ person in the village,” said Pandey.

It’s reminiscent of Ashutosh Gowariker’s Swades (2004), about the journey of NRI Mohan Bhargav to his Parvati Amma’s village. Gowariker, who earlier made the blockbuster Lagaan (2001), again set in a village in Rajasthan, took a detour from the masala movie formula in Swades. Between 2004 and 2012, several filmmakers including Rao and Shyam Benegal turned to rural India to tell stories.

In Benegal’s satire, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), an aspiring novelist named Premchand Mahadev (Shreyas Talpade) has to make a living by writing letters for villagers. But he is manipulative and shrewd. He tries to ‘steal’ his crush Kamala (Amrita Rao) from her husband who works in the city. Benegal’s film also focuses on child marriage and superstitious practices like marrying off a ‘manglik’ woman to a dog. Despite its often risqué humour, the film offers sharp social commentary on many issues in rural areas.

In Peepli Live (2010), producer Rao and Aamir Khan delve into the tension between farmers’ suicides and the breaking-news-hungry media, and in Paan Singh Tomar (2012), Irrfan Khan plays a national-level athlete who becomes a dreaded dacoit in the Chambal Valley. Both movies were hits, but the village as muse faded from the big screen until OTT and Panchayat.

Also read: With 12th Fail, Bollywood discovers Mukherjee Nagar stories. Classes, clamour, commerce

The universal village

Panchayat reminded the audience of rural India on the brink of change. One where villagers had cell phones and aspirations. Created by TVF and released for the first time on Amazon Prime Video in 2020, the show is about a fictional village in Uttar Pradesh’s Balia district.

“The USP of the show is that it is carefully universal so far. It could be a village in UP, MP or even Rajasthan. Its humour is not because of the villagers’ way of life, but rather Sachiv Ji’s (Jitendra Kumar’s Abhishek Tripathi) lens, which is also the lens of the audience, an urban, educated one,” said Mihir Pandya, who teaches Hindi literature at University of Delhi.

Phulera becomes increasingly political in seasons one and two, as the feel-good element is fused with the current politics. But it resolutely stays away from things like caste discrimination, or even class bias within the village system of governance. With its ‘good at heart’ characters, Panchayat is a show meant solely for the city-dweller. Phulera seems like a village that may be a few kilometres away from the nearest rapidly expanding suburb but it rests and thrives on its own biases and governance systems.

A similar simplicity of thought frames the world of Rao’s Laapataa Ladies. The world of Mai, and the other characters—Phool, Deepak and Jaya— would fall into the bracket of the Gandhian ideal. It’s a push for feminism and the importance of female friendships. Deepak (Sparsh Shrivastava) accidentally takes another newlywed woman, Pushpa Rani (Pratibha Ranta), home instead of Phool (Nitanshi Goel). The case of mistaken identities is complicated by a corrupt police inspector, Shyam Manohar (Ravi Kishan). What happens next forms the crux of the story.

Laapata Ladies trains its eye on the women, and their lived experiences and dreams. Phool is learning the importance of earning her own money, inspired by her benefactor Manju Mai. Even Deepak’s mother (Geeta Aggarwal) and his grandmother try to be friends. Jaya’s friendship with Deepak’s sister-in-law also helps the latter turn her hobby of sketching into something she could pursue professionally.

The writers Biplab Goswami, Sneha Desai and Divyanidhi Sharma infuse an entrepreneurial spirit in the female characters to show why it’s important to have an ecosystem of support and financial independence. Here, the men are the supporting characters, while women discover themselves, offering a much–needed inversion of the usual trope of men trying to figure out life.

But in Rao’s interpretation of village life, there is no major conflict. Even the looming dangers of bride-burning and dowry death are effectively resolved, which is never the case in real-life scenarios.

There is an element of nostalgia, from Nokia mobile phones, to radio, and PCOs and bicycles.

“The thing about Laapataa Ladies or even Varun Grover’s All India Rank (2023) is that they are set in a world before the internet age, and with no or nascent models of mobile phones. That is the only way a certain kind of innocence can be portrayed,” said Pandya.

In Panchayat, even the humble bottle gourd or ‘lauki’ is in the spotlight. The Indian village with all its mundanities and problems is being re-imagined to appeal to the overworked and jaded corporate employee.

“These films and shows have opened up a new sector of the urban bottom of the pyramid, where the working class too are nostalgic about village life. It is no longer the middle class or NRI yearning for it,” said Nandy.

For Nandy, it is not unusual for a city dweller to soak in the oddities and eccentricities of the village life, not permanently, but as a ‘learning curve’. Even Rabindranath Tagore went to Santiniketan, and other Bengali town dwellers followed suit, spending summers and winters in villages. Nandy ascribes it to the growing market for ‘rural tourism’.

“In a way, this is looking at India’s long-delayed return to its villages—even though the Indian village is not yet ready to be the next resort destination,” he said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)