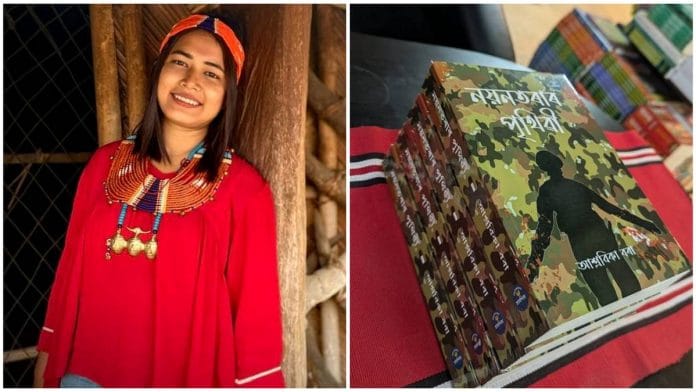

Guwahati: The midnight knocks started again. Nearly 30 years after Aashrawika Borah’s father laid down arms as an ULFA battalion commander, the police were back. This time for her. It wasn’t because she’d picked up weapons, but a pen—to tell a story inspired by her father’s militant past. Today, the 27-year-old from Solsoli village in Assam’s Nagaon district is one of the state’s most talked-about young novelists.

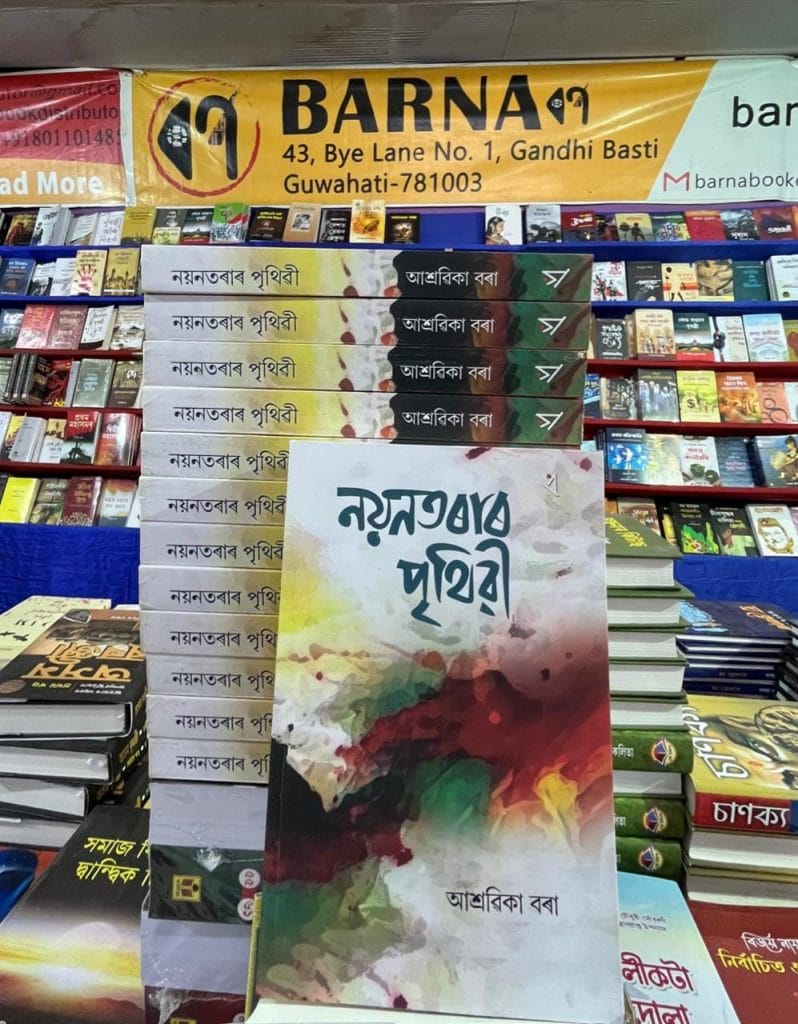

Her first book, Nayantora’r Prithibi (The World of Nayantora), the first Assamese novel centred on female ULFA cadres, was an instant hit in 2022 and is already into its eighth edition. An English translation is in the works, and so is a sequel. But the road to recognition was a years-long trial by fire. Borah, who began writing the novel when she was 20, travelled across insurgency-scarred regions in the Northeast and Myanmar to research it, and was summoned by the police when she started sharing chapters online.

“Hailing from a remote village, we had seen the impact of bandhs called by ULFA, how people would hardly go out of the house after 6 in the evening, security forces combing villages in search of militants. I used to hear stories of ULFA from my father like other kids hear folktales at that age. Later, when he read my novel, he was shocked because he also didn’t tell me so much about ULFA,” said Borah, her tone measured and unhurried.

Even when her work became risky and a potential threat to her career prospects while she was pursuing a master’s degree in history at Gauhati University, Borah knew it was a story she had to tell.

“Since childhood, I was isolated. Village people taunted me as a ‘militant’s daughter’. I used to feel ashamed,” she said. “That wound compelled me to write.”

Nayantora’r Prithibi is the first part of the epic journey of Nayantora, an innocent girl from an Upper Assam village who is drawn into the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), the armed insurgent group now banned by the government. Through Nayantora’s transformation into the feared militant Rupalim Rajkonwari, the novel traces a blood-soaked chapter from the state’s history, where the dream of a sovereign Assam galvanised thousands of young people to join rebel camps in Nagaland, Myanmar, and Bangladesh. Operation All Clear in Bhutan, carried out by the Royal Bhutan Army (RBA) with assistance from the Indian Army in 2003-04 crippled the organisation, but extortions, bombings, and other insurgent activities have continued to some extent even after that.

“The story of Nayantora aka Rupalim will continue in the second part of the saga called Tejor Sithi Mongxor Pristha (Letters of Blood, Pages of Flesh). It will be based on the events post Operation All Clear and should be released sometime this year,” said Borah, who is now an assistant professor of history at Roopohi College in Nagaon.

My father took arms training in the Kachin state of Myanmar. He was the area commander of a battalion before he decided to lay down arms and return to the mainstream in 1997. He had become disillusioned with the path of violence

– Aashrawika Borah

In the meantime, she has published another novel, Hardeng (Burning Charcoal), that covers a vast stretch of 1,300 years, from the fifth-century Tiwa kingdom to the Phulaguri uprising of 1861, Assam’s first major peasant revolt against British rule. Last year, she also co-edited a non-fiction anthology with Digonta Buragohain on Piyoli Phukan, among the first martyrs of Assam’s anti-colonial struggle.

And she is no less outspoken than before. Borah’s posts on identity, land rights, and tribal politics in Assam have often drawn heated reactions online. In November 2025, she challenged the All Assam Tribal Sangha’s opposition to Scheduled Tribe status for six communities

“Seeking constitutional safeguards for their community is a matter between these tribes and the central government. Why is Aditya Khaklary [Tribal Sangha general secretary] and team jumping in between?” she said in a Facebook post, only to receive an onslaught of insults and vulgar comments.

For eminent Assamese novelist Rita Chowdhury, Borah’s hard-hitting writing style is a strength that will hold her in good stead.

“She is very opinionated and has got a clarity of thought. If she can continue in the same vein, she will surely carve a niche in the annals of Assamese literature,” said Chowdhury.

Also Read: Indian parents are in a new race. Turning children into book authors is the new black belt

Her father’s daughter

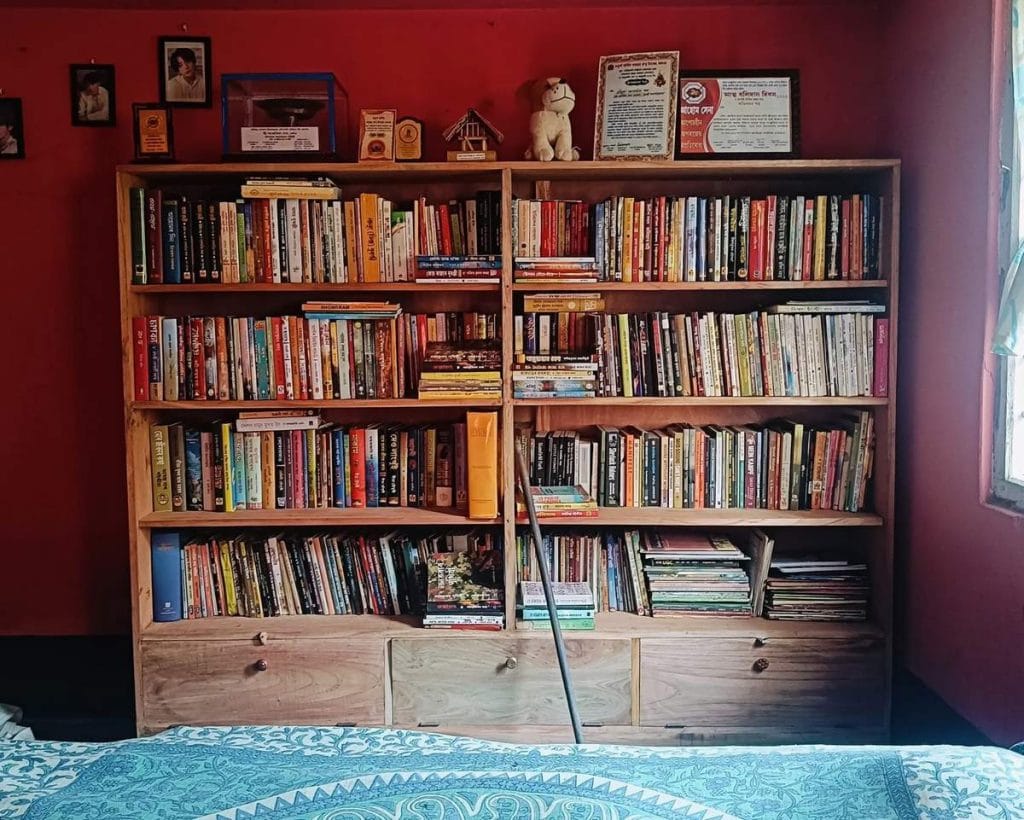

The shelves of Aashrawika Borah’s home in Solsoli, where she lives with her family, groan with books in Assamese and English, from Sherlock Holmes to a translation of Mein Kampf, to history tomes.

As an introverted child, books were her best friends. And it was her father who ignited a love of reading in her.

“There was always an atmosphere of reading in the household. Her father is an avid reader. I also like to read, especially the writings of Mamoni Raisom Goswami,” said Borah’s mother Kabita proudly. “She was also interested in writing from a young age. When she was in school, she once won the first prize in a writing competition organised by the Srimanta Sankar Sangha.”

The family’s daily life was uneventful. Her father grew til and mustard, after earlier running a small furniture business, and her mother works at the village panchayat office. Borah and her younger sister, an MA student in Dibrugarh, were taught the value of studying and building a career.

But from a young age, Borah kept gravitating towards the past—in her reading first, and later in what she chose to study. As a history student, she returned to novels about upheaval and loss: Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya’s Sahitya Akademi-winning novel Yaruingam on wartime Tangkhul Naga society, Rita Chowdhury’s Deo Langkhui, set in the 14-century Tiwa kingdom, and The Great Hunger by Cecil Woodham-Smith on the Irish potato famine of the 1840s.

Nayantora’r Prithibi… is masterful and stands as a lasting literary achievement. The author has entered the characters so deeply that, at times, Nayantora’s turmoil echoes Aashrawika Borah’s own inner conflicts, shaped by the same past

-Abid Azad, editor of the Guwahati Literary Festival

What tugged at her most as a writer, however, were the 12 years her father spent with ULFA, after dropping out in the first year of his BA at BKB College in Nagaon.

“My father took arms training in the Kachin state of Myanmar. He was the area commander of a battalion before he decided to lay down arms and return to the mainstream in 1997,” Borah said, who requested his name not be divulged. “He had become disillusioned with the path of violence and realised that his dream of an independent Assam will never be fulfilled.”

There was no dramatic exit. He simply melted away and began rebuilding his life.

“He never surrendered before the government and so he never received any aid from the state,” she said.

As Borah grew older, books and fragments of her father’s past stopped being enough. Unwritten stories began to press on her.

“All the novels written on ULFA were from the perspective of a male cadre, be it Sanglat Fenla or Aulingor Jui. So I wanted to write a novel on ULFA about a female guerrilla. I started my work on the novel in 2018,” she said.

She wrote mostly at night, sketching the structure and taking notes in longhand before drafting chapters on her mobile phone. Her parents encouraged her throughout the process.

But imagination and reading could only take her so far. To understand the geography of a rebellion, she had to walk it.

Going to ground zero

When she was still studying at Nowgong College, Borah’s research for Nayantora’r Prithibi began to move beyond books and phone calls. She initially spoke to overground ULFA members over the phone, but grew uneasy about the possibility of those conversations being monitored. In 2019 and 2020, she began travelling instead.

She paid for the trips herself. As a first-year BA student, Borah received Rs 1.54 lakh through the UGC’s Ishan Uday Scholarship, which is given to 10,000 students from Northeast. She also earned money through private tuitions, enough to fund her research without asking anyone for help. Years of travelling alone for national-level yoga competitions had made her comfortable navigating unfamiliar places. Once again, she had her parents’ blessings.

She made sure to do her homework before setting out.

“I learnt languages like Nagamese, Ao Naga, Bhutan’s national language Dzongkha from an online tutor and also a little bit of Burmese” she said.

Over an intense two years, Borah travelled through the Mon district of Nagaland and the remote outposts of Vijaynagar in Arunachal Pradesh, before crossing into former ULFA hideouts in Myanmar and Bhutan. Former ULFA cadres based in Nagaon helped her make initial contacts in villages, and those introductions eased her way.

But it was two women she met in Assam who crystallised the character of Nayantora-Rupalim in her mind. The first was a former ULFA cadre who had already surrendered her arms and returned to her native village in Sivasagar district.

“She was a simple village girl who retained her innocence even after joining the organisation. Unfortunately, she died during childbirth shortly after I met her,” said Borah.

The second woman was “a battle-hardened guerrilla” Borah first learned about in journalist Dhiru Moni Gogoi’s non-fiction book Nishiddho Joddha (Banned Warriors). Before seeking her out, Borah met Gogoi in Nagaon during his book tour in Assam and proposed the idea.

I went with my father to the SP office. They interrogated me for an hour. They asked why I wrote a novel on ULFA, from where did I get my information, if I was sympathetic to their cause. They thought my novel might influence the youth in joining ULFA

-Aashrawika Borah

“One of the chapters of my book was based on this lady guerrilla whom I met at Kakopathar at a designated camp for cadres who laid down their arms,” Gogoi recounted. “Aashrawika told me that she wants to base her protagonist on this person. She later went to Kakopathar and met her.”

The visit to Kakopathar in 2021 was disturbing for Borah.

“I stayed with the guerrilla on whom the character of Rupalim was based for three days and heard her entire story,” she recalled of the camp, which was set up by the government to house the cadres who had surrendered arms in 2008. “The cadres were living in sub-human conditions. They used to get an allowance of Rs 3,000 a month from the government along with ration. A long corridor had been turned into rooms using curtains, so there was no privacy. There were 15 families living there at the time, sharing a common toilet.”

Conditions at this camp have improved, according to recent reports, with most former cadres now returning to their original villages, but the experience has lingered with Borah. She said she plans to weave in her observations in the sequel Tejor Sithi Mongxor Pristha.

“Nayantora’r Prithibi sheds light on a shadowed, multilayered, fearful, and profoundly courageous chapter of Assam’s past,” said Abid Azad, editor of the Guwahati Literary Festival. “The book is masterful and stands as a lasting literary achievement. The author has entered the characters so deeply that, at times, Nayantora’s turmoil echoes Aashrawika Borah’s own inner conflicts, shaped by the same past.”

But this nuanced writing also landed Borah in trouble.

Midnight knocks

As the book neared completion in 2021, Borah started uploading excerpts from Nayantora’r Prithibi on Facebook. At first, the responses buoyed her.

“I had uploaded 18 brief episodes, mostly 2-3 paragraphs long, on Facebook and they were getting great responses from readers,” Borah said.

One excerpt captured protagonist Nayantora’s slow hardening inside the insurgency:

“The girl who felt dizzy at the sight of blood had to cross thousands of canals of blood. She had to protect her soft heart with a stone armour so that she could carefully safeguard all the experiences and sensitiveness and existence she had before joining the organisation….”

However, her posts, which she started sharing in January that year, also got the attention of the police, especially descriptions of ULFA camps.

Sometimes they would knock at our door after midnight and ask the whereabouts of Aashrawika. This led to gossip in the village that she must be involved in some mischief though we didn’t care about such talk

-Kabita Borah

The summons started coming from February 2021. Borah was first called to the local police station at Samaguri and asked to add a disclaimer to the Facebook posts stating that all characters were fictional, and to give an undertaking that she would stop writing the novel. Borah agreed to the disclaimer but refused to sign the undertaking. Soon after, she was summoned to the office of the Superintendent of Police in Nagaon.

“I went with my father to the SP office. They interrogated me for an hour. They asked why I wrote a novel on ULFA, from where did I get my information, if I was sympathetic to their cause. They thought my novel might influence the youth in joining ULFA and so they deleted all the chapters I uploaded on Facebook,” she said.

She did not upload the novel again online, but she did not abandon the manuscript either. She became more cautious instead, saving her work across multiple devices in case her phone was seized.

Kabita Borah said the police monitored her daughter’s movements for quite some time.

“Sometimes they would knock at our door after midnight and ask the whereabouts of Aashrawika. This led to gossip in the village that she must be involved in some mischief though we didn’t care about such talk,” she added.

It didn’t help that in December that year, a Facebook friend of Borah ran away from home and joined ULFA.

“She was an acquaintance with whom I used to interact on Facebook as our wavelength matched on a lot of things. I had met her only once in Guwahati. My book had nothing to do with her decision as she had not read it,” Borah said.

Gogoi pointed out that the state is always suspicious of any book written on a banned militant outfit and that he too was accused of being an ULFA sympathiser.

“Of course, I was not grilled by the authorities because of my stature as a journalist. The fact that Aashrawika’s father was earlier part of ULFA also raised their suspicion,” he said.

Ironically, what finally ended the police visits was not Borah’s silence but how much her book resonated with the public when the book came out.

“When the book got popular after publication, those midnight knocks from the police station also stopped,” laughed Kabita.

When she’s not teaching or writing, Borah speaks at literary festivals and book fairs across districts such as Nagaon, Sivasagar, Jorhat, and Tinsukia. She now receives advances and royalties, and messages from readers regularly arrive on Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram. She has also received a few hand-written notes. Her readership, she said, has largely been in the 30-60 age group.

Also Read: Hindi literary mag Nayi Dhara gets a reboot. For Ashoka University founder, it’s personal

ULFA on the bookshelf

Nayantora’r Prithibi takes on a violent and complicated history, but it is also a pacey transformation story, complete with subplots of love and betrayal.

Shikha Baruah, a 42-year-old social worker from Digboi, read the novel in 2022. Growing up in the oil town in the 1990s, she lived close to Kakopathar and Lakhipathar, areas that were once hubs of ULFA activity, and has always been interested in fiction set in that period.

“Growing up in an Upper Assam town in the early 90s was like sitting on top of a box of dynamite. That era saw the peak of ULFA’s activities,” she said. “Despite not witnessing that period personally, Aashrawika did full justice to the era in her book. I find the same courage in Aashrawika’s pen that I found in Anuradha Sarma Pujari’s writing.”

The novel was also a pathbreaker as the first work of long fiction on women ULFA cadres, according to Gogoi. His own Lady Guerrillas, the third book in his ULFA series, was published in 2022 but was non-fiction. Another novel on women in ULFA, Juri Borah Borgohain’s Netri (Leader), was released later, in September 2024.

The first six editions of Nayantora’r Prithibi were published by Pragya Mediahype. Its proprietor, Ujjal Bora, who had earlier published Gogoi’s Nishiddho Joddha: Banned Warriors, had expressed interest in Borah’s manuscript as early as 2020, when he accompanied Gogoi on a book tour in Assam. As excerpts of the novel began circulating online, Bora formally offered to publish it.

Later editions were taken over by Prakashika, one of Assam’s oldest publishing houses. Each print run has been 1,000 copies, sold largely through bookstores and book fairs.

“Generally, our agents read books and advise us on what to publish. But in the case of Nayantora’r Prithibi, I myself read the book and decided to publish it,” said Manab Deb Choudhury, proprietor of Prakashika. “Even four years after its first publication, it is getting a solid response from readers. We published her second novel Hardeng, and we will be publishing the English translations of both books.”

Choudhury said his house has no qualms about publishing books on ULFA. Apart from Borah’s work, Prakashika is also publishing Gogoi’s series and ex-ULFA general secretary Anup Chetia’s ULFA’r Oxomapto Itihaas (ULFA’s Unfinished History).

For Borah, the insurgency is neither something to romanticise nor dismiss without examining the political neglect and economic marginalisation that led to it.

“Today, ULFA has more of a negative image among the youth for their many, many misdeeds over the years. But the reason why ULFA was formed and how hordes of youngsters shed blood for the dream of a sovereign Assam can never be overlooked. But I, or my books, will never encourage anyone to join the organisation today.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)