New Delhi: At a time when history books are being rewritten across academia, a bunch of historians, professors and students filled the hall at the India International Centre for a discussion on narrative panels—the story plates depicting mythological tales—found in temples across the country. The key question was ‘Who decided what was depicted on the narrative panels and who paid for them? This debate about patronage is a long-standing one among historians.

After an hour-long presentation by Aparajita Bhattacharya, associate professor at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, there was no consensus. There is no way to directly link the Gupta royalty, who are the central figures in the reigning theory regarding patronage, to these temples. We need an alternative approach to understand the patronage question, said Bhattacharya.

But the conclusion of the talk offered no hope—”There is no easy answer,” she said.

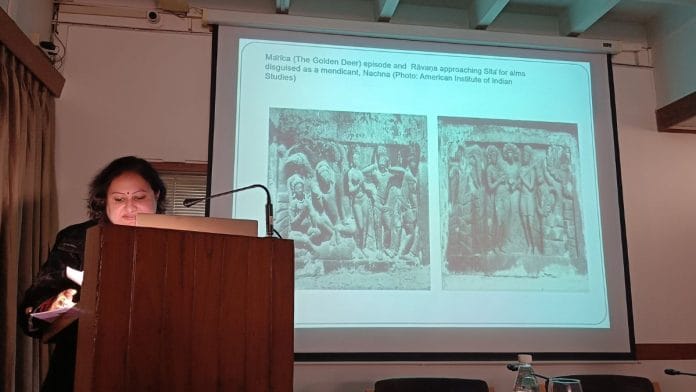

The event took place just a day after the grand consecration of Ram at Ayodhya and focused on the temples of Central India during the 4th to 6th centuries. Historians showcased the ancient panels showing the mono scenic views of the Ramayana and other epic myths to a rapt audience who had a long list of questions.

According to Bhattacharya, the temples have no inscription and no involvement of royals or the political authority behind their rise and development.

The talk titled History and Heritage: The Afterlife of Monuments was curated by historian and archaeologist Himanshu Prabha Ray. It was chaired by Delhi University professor Seema Bawa, who specialises in the history of South Asian art and culture.

“The Study of Gupta temples is Bhattacharya’s fieldwork. Most of her work is an amalgamation or synthesis of epiography with theory and heritage,” said Bawa.

The experts said that some of the temples that while these are from the Gupta period the rulers weren’t the ones patronizing them.

“ASI old records, particularly two reports by [Alexander] Cunningham said these temples are from Gupta periods but if we go on the site and inspect, the Gupta rulers of ancient India have no role in the development, sustenance and the continuation of these temples,” said Bhattacharya.

Seema Bawa was in agreement, stating that there is no direct linkage with the Gupta era and the temples did not thrive on royal patronage. However, she added that “they do have linkage with subsidiary kings (Parivrajaka and Uchkapla) in this era. Traders also give some kind of patronage to the sites on the Betwa route of the Bundelkhand region.”

In exploring the significance of these temples, it’s essential to consider the broader context of temple architecture in India, particularly how various regions, including Bundelkhand, have contributed to the rich tapestry of Hindu religious sites.

Also Read: Hindus didn’t record their history right. Indraprastha’s foundation, age still uncertain

Vishnu panels

Temples showcased by Bhattacharya were from the Bundelkhand region of UP and MP. The selection of temples is based on the availability of narrative panels. The pieces are preserved in museums across India.

“One of the curious tendencies of these temples is that the forehead of the temple (lalatabimba) actually gives a clue to which god the temple belongs to,” said Bhattacharya pointing towards the images of the panels which she photographed during her field visits.

Bhattacharya said that the temples of that time were adorned by narrative panels which represented various myths. The position of these panels is very important. “These panels are not on the walls of the temple but on the plinth area mostly on horizontal bands and these are mostly monoscenic in nature. It actually anticipates the existence of the informed audience,” she said.

In one of the narrative panels at the Dashavatara Temple of Lalitpur, Vishnu sits on Sheshnag with two attendants, Narsingh and Vamana. “The incarnations are portrayed as associates of the main deity. Before entering into the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum), devotees have a clue about the deity,” said Bhattacharya.

Other panels show Vishnu sitting on the lotus. In another one Vishnu’s weapons are shown in human form. Other panels show a cosmic view of Vishnu, where devotees pay homage to Vishnu. One of the Trivikrama panels shows the iconography details of the lost temple of Pavaya, Gwalior.

The scale of these panels is gigantic. “Some of the inscriptions are in damaged form and scholars have different views on them. Conservation and the politics or techniques of conservation affect the very nature of the sites,” said Bhattacharya.

Also Read: Delhi durbars flaunted the might of British Crown. They also stoked flames of resistance

Question of location

Bhattacharya also used their location and the absent Gupta epigraphy in these temples to answer the patronage question.

“…they are all located in forests. Ethos of forests is very much ingrained in the regional psyche of the people of that time. Location of these sites are very remote from the political heartland of the Gupta rulers,” she said.

Bhattacharya pointed to a panel depicting the Aranya and Kishkindha kand of Ramayana where Ram and Lakshman were greeted by monkeys. One shows the fight between Sugreeva and his brother Bali and another one shows the confusion Rama faced to kill Bali because both brothers have the same face. “They give us a window to understand the kind of narratives selected for representation during the common era,” said Bhattacharya.

One of the audience members asked the professors about the Jain narrative panels in western India. “Places all over in India have Jain narratives. Bade ghumte firte log the [They were serial travellers],” Bawa laughed.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)