New Delhi: Swami Vivekananda’s popular saffron-robed, turban-clad image has become a subject of controversy today. The BJP-RSS hail him as their icon, while ideological adversaries accuse Right-wing parties of “appropriating” him. Does it become important, then, to release another book on the illustrious Hindu monk and philosopher?

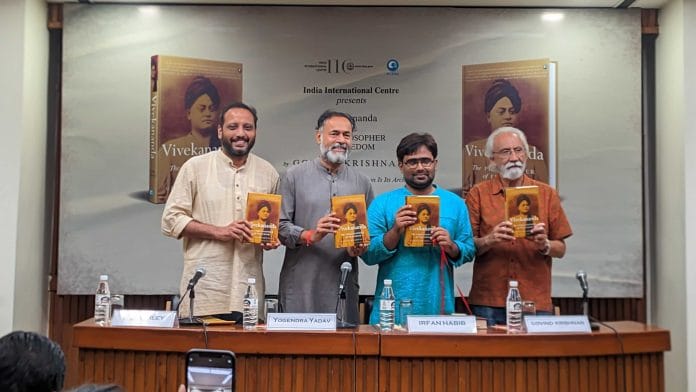

Those who do not subscribe to the RSS-BJP school of thought certainly think so, which is why they recently gathered at Delhi’s India International Centre to discuss Govind Krishnan V’s new book, Vivekananda: The Philosopher of Freedom.

“Whatever the Sangh Parivar touches, the secular liberals run away from that. We help them in cultural appropriation by abdicating the same ideas and figures. Unfortunately, one of the first victims of this appropriation was Swami Vivekananda,” said activist-politician Yogendra Yadav, who was part of the panel discussing Krishnan’s latest work.

There is topical sensationalism around certain figures, added NP Ashley, a Delhi University English professor who was moderating the event. “What scholars and academic conversations should do is allow us to reconsider the preconceived notions, which this book aims to do.”

Vivekananda’s ideas

Since coming to power, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has quoted Vivekananda multiple times, even proclaiming that he once wanted to become a monk at his Ramakrishna Mission Ashram. When former US President Donald Trump visited India for the ‘Namaste Trump’ event in 2020, he, too, took – and famously mispronounced – Vivekananda’s name. Congress wasn’t far behind either. Rahul Gandhi started his Bharat Jodo Yatra from Kanyakumari last year, paying tribute to the Hindu monk at Vivekananda Rock Memorial.

Through his book, Krishnan attempts to show that Vivekananda’s religious philosophy, social thought, and ideology are the very antithesis of Hindutva.

“There are four aspects to focus on, in which Vivekananda’s philosophy differs from the RSS or challenges it: his attitude towards religion, specially Islam and Christianity; his interpretation of Hinduism; his attitude towards the West, which is as different as day and night from that of [the] Sangh Parivar; and the fact that Vivekananda was an extraordinary individualist while the RSS believes in a certain collectivism,” said Krishnan.

The author devotes 13 chapters to this ideological contrast. In sections titled ‘Vivekananda’s Hinduism vs the Sangh Parivar’s Hinduism’; ‘The Individual and Society: Vivekananda and the RSS’, and ‘The Political—Gender and Caste’, he details various contentious issues and Vivekananda’s stance on them, which liberals and secularists have been quick to denounce.

Historian S Irfan Habib, also part of the panel, pointed out that Vivekananda remained receptive to a wide array of influences, arguing how his speeches and writings are relevant in today’s context, particularly the interpretation and teaching of medieval Indian history.

“In his essay Future of India, Vivekananda suggested that the Mohammedan conquest of India had a liberating impact on the downtrodden and impoverished segments of society. Those who currently claim his legacy should consider his views on this historical period,” Habib said.

Moreover, added the historian, Vivekananda extensively visited monuments from the Mughal era. He explored Sikandra and Fatehpur Sikri in Agra, Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, and the Imambara in Lucknow. “He expressed admiration for Akbar, whom he regarded as one of India’s greatest rulers following Ashoka.”

Also read: Swami Vivekananda is not a Sangh Parivar icon. Liberal-progressives allowed his appropriation

A complex debate

Krishnan acknowledged the complexity of the debate surrounding Vivekananda. Perhaps this complexity arises from the fact that, while there is a vast literature available on Vivekananda, whose own body of work spans nine volumes and 5,000 pages, most Indians have only read his famous Chicago speech. Some misinterpretations depict him as a proponent of caste hierarchy and Hindu supremacism, a characterisation that Yadav disputed.

“Was he a proud Hindu? Yes. Did he believe there was something special about Hinduism? Perhaps he did. But can you accuse a preacher of a religion for believing that there is something special about his religion? No, because that is why he is a preacher. But was he a Hindu supremacist? He was not; that is the whole point. That is what he has been reduced to,” said Yadav.

The audience also questioned the absence of any mention of Vivekananda’s spiritual parents and gurus, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Sarada Devi. Krishnan clarified that he did not approach the book as a biography but as a chronicle of Vivekananda’s ideas, challenging preconceived notions. He also did not have the spiritual intent or authority to write about them, he said.

While one audience member suggested translating the book into Hindi for wider reach, another asked about Ambedkar’s interpretation and perception of Vivekananda’s idea of Hinduism. In response, the author quoted from the last chapter of his book, mentioning “interesting convergences” between Vivekananda and Ambedkar on the matter of caste and Hinduism.

Yadav then spoke about how Indians are particularly neglectful of their own historical canons.

“If Greek philosophy is revered all over the world, it’s not just because Plato and Aristotle wrote some nice books. They also wrote things that were not nice. It is the canon-building around them in the Western tradition over the centuries that has made them enduring figures. We don’t remember Aristotle solely for supporting slavery; we remember him for many other sensible things,” he said.

Yadav emphasised that Indians are especially attentive to their thinkers’ problems, particularly the minor differences they had 100-150 years ago. He called it “historical anachronism”, or judging historical figures by today’s standards.

“You don’t judge Gandhi, Ambedkar, Vivekananda, or Narayana Guru by what you think about caste today. It’s a mistake to read back into the history of ideas and project our current assumptions onto thinkers.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)