New Delhi: Long before Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose became an iconic figure in textbooks, especially in West Bengal, his image circulated widely through calendars, posters, lithographs and mass-produced prints that travelled across colonial India. An exhibition in Delhi argues that these images did not merely document history — they produced political memory.

Curated by Neville Tuli for the Tuli Research Centre for India Studies (TRIS), the exhibition, India’s Visual Political Iconicity (Part 2) – Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, opened on 26 January at Delhi’s India Habitat Centre, as part of the ongoing sixth Self-Discovery via Rediscovering India Festival. The event will conclude on 29 January.

The exhibition follows the first part of the series, which focused on MK Gandhi, and forms part of a larger framework examining how Indian political leaders were transformed into mass icons through popular visual culture. Tuli told ThePrint that the idea grew out of a sustained engagement with printed political imagery produced in the early decades of the 20th century.

“A focus on the life and times of Gandhi was Part 1. We had Six Individual Political Icons who had visually fascinated the Indian Printing Presses post 1900-05 period — Lok Manya Tilak, Mahatma Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, Subhas Chandra Bose, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, and Sardar Vallabh Patel. Thereafter, we had the Institutional Framework, and then the next 24 related Icons,” he said.

‘Visual political iconicity’

At the centre of the Bose exhibition is the idea of “visual political iconicity” — a term Tuli uses to describe how mass-produced images shaped public understanding of political figures long before radio, television or digital media.

“You have to assume that the printing and publishing presses of India, which were producing political propaganda in the millions of paper-based documents, most now destroyed, had a sense of the public perceptions and excitement of that personality. As a result, every press across the country produced their own variation of the person, event, idea, image, etc., and shared it with the public, which in turn further reinforced public perception,” he said.

Drawing on an archive built over three decades, Tuli situates Bose as one of the most visually powerful figures of the freedom movement.

“Having built the largest archive in the world over 30 years, it was clear that after Gandhi, Netaji had captured the hearts of the common Indian, followed by Bhagat Singh and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, and most importantly, the imagery had a certain visual power and energy which aided the concept of visual as a source of knowledge,” Tuli added.

The exhibition traces Bose’s life through early portraits, his re-election as Congress president in 1939, the formation of the Azad Hind Fauj in Singapore between 1942 and 1943, and the INA’s campaign culminating at Kohima in 1944. It also places Bose within the wider political landscape of the freedom struggle, including his relationships with Gandhi and Nehru, and his alliance with Japan during World War II.

Decisions about what to include, Tuli said, were shaped by both availability and context.

“The subject quality and quantum of the printed visual materials decide what is to be covered initially, as so much is now destroyed. Thereafter, the aesthetic and technological issues related to that artwork, and then the subject it represented within the larger context of Seeking Justice and Political Integrity (the 13th Research Category of 16),” he added.

A substantial section engages with Bose’s frequent depiction in military attire, a visual association that Tuli argues is inseparable from his political journey.

“He is the true scholar-warrior in the more traditional sense, and his establishment of the Azad Hind Fauj (INA), collaborating with Japan and its then Prime Minister Tojo to gain access to the Indian Prisoner Of Wars was an important part of India’s struggle towards independence,” he said, adding that many try to place this revolutionary struggle on par with the non-violent struggle, but that is unfair and creates divisions and misunderstandings.

The exhibition — intended primarily for students and educators — also showcases internal rifts between the national movement, particularly how figures were visually positioned immediately after independence.

For visitors who are encountering Bose for the first time, Tuli wants them to take away “renewed energy and some idealism” from the exhibition. “Our country is deeply unaware and uneducated in the visual vocabulary,” he added. “Improving this is critical for India.”

The exhibition showcased three portraits that stood out.

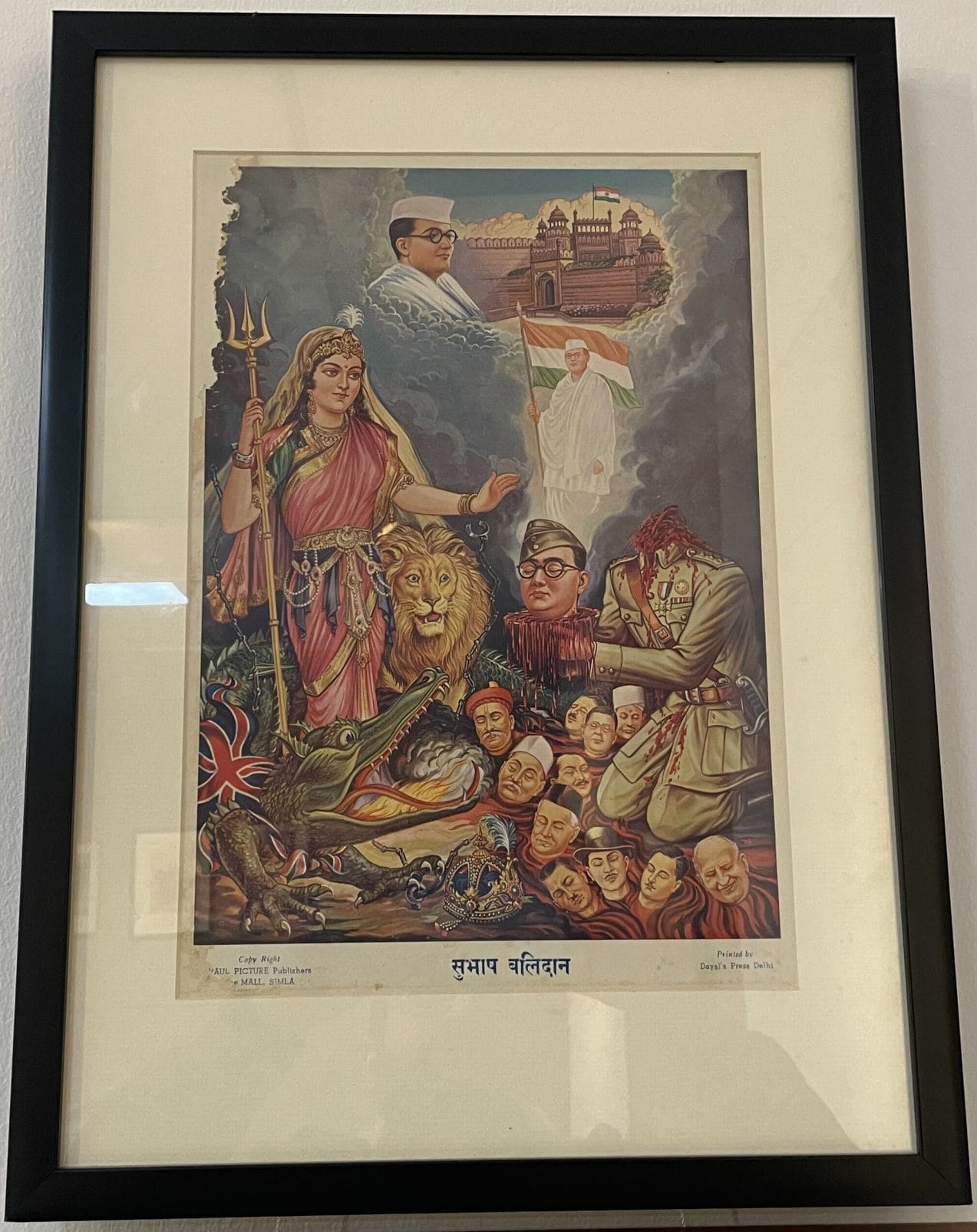

Subhash Balidan

The first portrait displayed the self-sacrifice of Bose to India, with other freedom fighters — such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Motilal Nehru, Surendranath Banerjee, Bhagat Singh, and Raj Guru — in a stream of blood.

Also read: ‘Don’t take family photos for granted’—Turkish scholar uses old images to capture history

India-Japan friendship

This portrait was an artwork with a mix of hand-painted landscapes by anonymous Nathdwara-based artisans with photographic cut and paste montaging, which focuses on the India-Japan friendship and collaboration led by Bose and supported by Gandhi and Nehru. It has Mount Fuji in the background and the Laughing Buddha, Japanese children, and cats in the foreground, all symbolising the togetherness during the 1944-46 period.

A message of love

Another artwork shows a truly syncretic version of India, created by the fusion of the energies of the spiritual-political leaders who took space within Indian civilisation — from Buddha to Jesus to Swami Vivekananda, from Gandhi to Bose to Sardar Patel, C Rajagopalachari, Nehru and Rajendra Prasad.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)