New Delhi: Over two decades ago, the Indian government was fighting hard to prevent the inclusion of caste discrimination at the international conference on racism in Durban. Some Dalit groups in India pushed for it. Prominent public intellectuals either resisted it or were largely indifferent.

It was during this time of “colossal indifferentism”—a term coined by Ambedkar’s aide Bhagwan Das—that the idea of having a small, independent anti-caste English language publishing house called Navayana took birth, reminisced S Anand, its Brahmin co-founder.

“Navayana was born at a time when this indifference was suffocating,” Anand recalled. “Back then, you wouldn’t know where to even buy Ambedkar’s works in English.”

Ambedkar’s seminal works had been largely kept alive by small Dalit presses in regional languages across India for decades. But the big city English readers remained blissfully unfamiliar with his ideas.

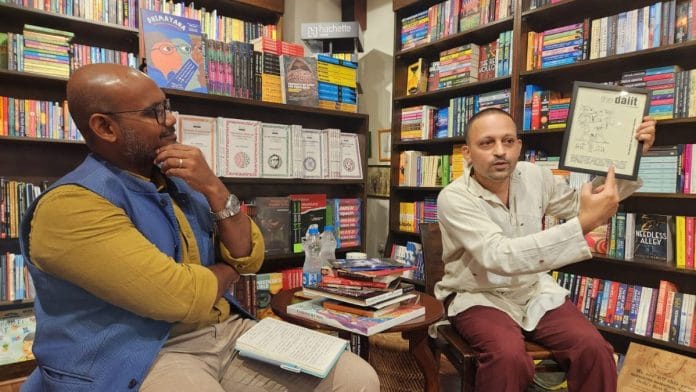

Today, Navayana has just four employees, including Anand. “We survive by being small,” he told IIT-Delhi professor Dickens Leonard during a talk at The Bookshop in New Delhi.

The story of small, independent publishers such as Navayana, Yoda Press, Panthers’ Paw and Zubaan is one of gritty individual vision. It also reflects a certain new blossoming of English-speaking readership in urban India, and its growing appetite for diverse voices. They hustle in a system dominated by corporate publishing giants that produce homogenised offerings for large markets where self-help books, textbooks and mytho-fiction set the cash registers ka-chinging. With limited money and nimble, multi-tasking staff, they seek to upend and expand the established rules of the literary marketplace and scholarship.

“A lot of the books we do actually don’t sell,” Anand said. “When you encounter the big press, they are like the standing Indian Army, and you are like a small stone-thrower. How do you intervene and occupy space?” Navayana produces eight to 10 titles a year currently and the goal is to take it to 25.

The first few books were slim ones priced at Rs 40 and Rs 60. They included Ambedkar’s Waiting for a Visa published as Ambedkar: Autobiographical Notes, and Touchable Tales.

“We said we shouldn’t make books unaffordable. And then the first distributor said they usually take a 40 per cent discount. I said what?” Anand recalled. “Today, I give 62.5 per cent. So, we have grown now in that sense. It’s a story of having to give up double and keep growing. This is how capitalism works.”

But they needed to do more than just slim books. They needed spine.

The fifth book was a collection of columns by Chandrabhan Prasad in The Pioneer newspaper, the 2004 publication titled Dalit Diary, 1999-2003: Reflections on Apartheid in India. With that, Anand gave his books the proverbial spine – of at least 224 pages. In 2009 came another thick volume called Dalits in Dravidian Land by S Viswanathan, a collection of articles on caste atrocities in Tamil Nadu between 1995 and 2004.

Disrupting caste narratives

The first book that he hoped would last long was Namdeo Dhasal’s collected poems with essays, interviews, and photographs. It was titled Poet of the Underworld (2007).

“Dhasal was the most important 20th-century poet. This, for me, was really the first big book. And then it breaks your heart,” Anand said. It took four years for it to sell just 1,400 copies.

He deliberately kept the publishing house as a for-profit enterprise. Both Anand and Ravikumar—a Dalit public intellectual, politician and the co-founder of Navayana—were sceptical of the NGO mode of doing things. Along the way, Navayana distributed via IBD and HarperCollins India, won the British Council’s international Young Publisher of the Year award, and received a grant from the Prince Claus Fund for a beautiful graphic book called Bhimayana (2011), richly illustrated by artists Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam.

Then came the whale – a book that Leonard said conquered the market. It was the globally accessible annotated edition of Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste. Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy wrote a long introduction. The book made Ambedkar’s work travel farther than it had until then, but also became controversial because of Roy’s overhang.

Getting Roy to write the introduction was strategic because “Savarnas were not reading Ambedkar”, Anand said. His works were “orphaned by Indian society and only the Dalits kept it alive”.

“Navayana disrupts hegemonic caste narratives by publishing radical works that challenge the status quo. This approach makes publishing a tool of cultural resistance, reshaping caste discourse and democratising knowledge,” said poet Anilkumar P Vijayan, who published his collection with Navayana under the name A-Nil. Earlier, Navayana has published poetry by ND Rajkumar, Meena Kandasamy and Cheran.

It was also the first to break the awkward silence on MK Gandhi’s racism in South Africa with the 2015 book titled The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire.

Also read:

The rise of anti-caste literature

A lot has changed in two decades. Today, politics and readership have flipped dramatically. There is a recent attention to anti-caste writing in the global press too, Leonard observed. Sujata Gidla, Yashica Dutt and Vauhini Vara are published abroad first and find a ready market in India. Literary agents are now seeking out Dalit voices too. Independent publishers are not ghettoised as esoteric by the market.

His next whopper is CB Khairmode’s intimate biography of Ambedkar. A Navayana reader named Abhishek Uchil is translating it from Marathi into English.

“It forces you to see an Ambedkar that you didn’t know – as a son, as a brat who stole eggs and chicken, as an indifferent father, as a husband who didn’t cut a very good figure, and at once as a great man that he was,” said Anand.

The long-term goal is to raise funds to put together an anti-caste children’s literature series. Anand’s first children’s book, Turning the Pot, Tilling the Land, with text by Kancha Ilaiah and illustrations by Durgabai Vyam, came out in 2007—and became a “jugaad hit”.

“Am I a children’s publisher? No. But is anybody else going to do an anti-caste children’s list? No,” he said.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)