New Delhi: Translator and literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil is often told she should ‘go to Pakistan.’ Her new book is an answer to that bigotry.

“It hurts, but at the same time I feel this should not be ignored. The hostilities we face since the rise of social media need to be confronted,” said Jalil at the launch of her new book Whose Urdu Is It Anyway? Stories by Non-Muslim Urdu Writers at Alliance Francaise de Delhi on Friday.

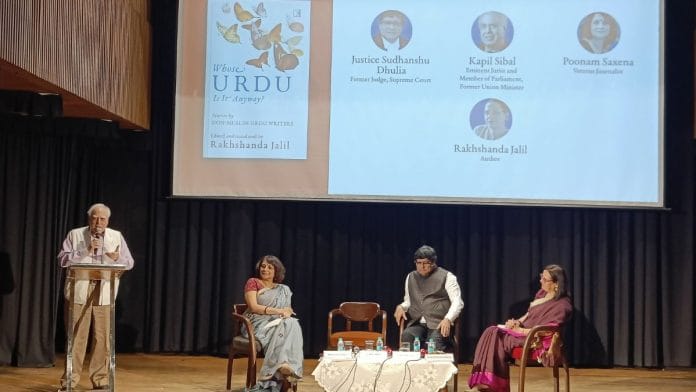

“Why should I go to Pakistan? Why can’t I speak in Urdu while living in India?” she asked, speaking in Urdu. Jalil was joined by former Union minister and jurist Kapil Sibal and former Supreme Court judge Sudhanshu Dhulia, at the event moderated by senior journalist Poonam Saxena. The panelists discussed the Hindi-Urdu debate and its politicisation over the years.

In February, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath criticised the Samajwadi Party in the state assembly for demanding translation of House proceedings in Urdu, saying they send their own children to English-medium schools but want others to learn Urdu and become maulvis.

The panelists at Jalil’s book launch condemned the politicisation of Urdu.

“There was extreme politicisation of language, but after 2014, it’s gone to the other extreme. Now, it’s become a weapon and when language becomes a weapon of hate, there is no hope,” said Sibal.

He added that the language can’t be protected without changing the way politics is done in India.

Also read: Urdu literature has ignored Dalit Muslims. Pasmandas must own the language

‘A crude expression’

The subtitle of Jalil’s book, Stories by Non-Muslim Urdu Writers, grabbed the attention of Justice Dhulia, one of the panelists, who is learning Urdu. “I found it a very strange thought,” he said.

Jalil’s book is the compilation of 16 Urdu stories by non-Muslim writers, including Krishan Chander and Gulzar. She said the subtitle of the book was a crude expression.

“It still makes me cringe. But I think the exigencies of time are such that we need a sledgehammer sometimes… they need to be said in this way,” said Jalil.

She noted the political agenda behind this. “I want to translate text that speaks to me in some way. Urdu has a lot of overtones. I wanted that to be highlighted.”

The talk sought to counter the stereotype about Urdu that it’s the language of Muslims. “I wanted to bust that stereotype. I wanted to say that Urdu is the language of India, not just Indian Muslims,” said Jalil.

Justice Dhulia argued that the younger generation should speak up and say Urdu is our language.

“It is an Indo-Aryan language, which was born in India. It did not come from outside,” he said.

Dhulia spoke about Urdu’s association with the national freedom movement, noting that even in pre-independence Congress meetings and in the Constituent Assembly, Hindustani was debated as a national language. But, he said, the real problem began with Partition.

“As Pakistan adopted Urdu as its national language, people’s anger towards Muslims and Pakistan came to Urdu as well,” said Dhulia.

‘Language will live despite hate’

Sibal recalled his “historical connection” with Urdu. His late father, lawyer Hira Lal Sibal, had defended giants of Urdu literature like Saadat Hasan Manto and Ismat Chughtai. “My father had a phenomenal wealth of knowledge in Urdu literature. It’s my misfortune that I did not learn Urdu to date,” he said.

Sibal blamed India’s politics for Urdu’s association with a religious community. He said today’s challenge is to protect the idea on which Indian Constitution was based.

“There is no institution that is willing to protect it, including the judiciary. You can’t protect a language without protecting the values on which this great country was formed, this great republic was formed,” Sibal said.

But he insisted that the language will remain alive despite the conflict and hate.

“The language is part of our culture and it has to be protected. Institutional patronage is the most important thing.”

But at the heart of the discussion lay a bigger question — how will the Urdu language thrive? Justice Dhulia had an answer.

“Urdu will become popular, and people will read and learn it, only when it is related to employment and commerce. It is not that only the state will [have to] do something. It will be difficult until people connect it to employment and commerce,” said Dhulia.

(Edited by Prashant)