New Delhi: Throughout her career in India and abroad, Zohra Sehgal brought every role to life — from Parosi to Bhaji on the Beach—with unmatched passion. Yet in Delhi, she was often reduced to being known merely as “Kiran Segal’s mother”, a label she quietly but fiercely resented.

“Wherever we used to go, people would say, ‘You know who she is? She is Kiran Sehgal’s mother.’ She would resent it. She didn’t like it,” said Kiran.

At social gatherings, when Kiran mentioned enjoying meeting old friends, her mother would sharply reply, “What fun? No one noticed me.”

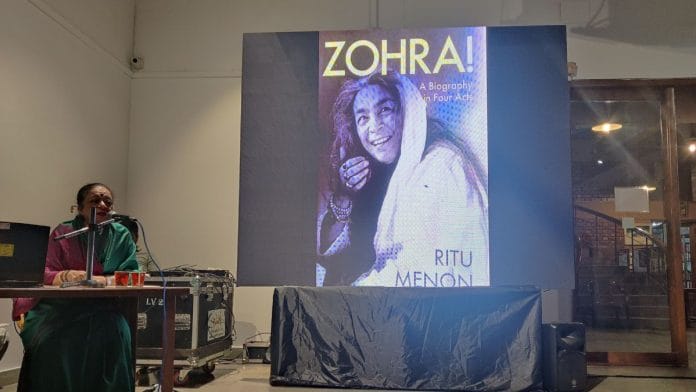

These and many more anecdotes were shared by her daughter, Kiran Segal, during the event Ghar ki Murghi Daal Baraabar held at Delhi’s Academy of Fine Arts and Literature on 19 September. It brought together friends of Zohra Sehgal, students associated with the academy, and devoted fans for an evening of stories, slides, videos, and an engaging Q&A session.

Zohra Sehgal lived her life with flair, fearlessness, and a wicked sense of humour. She trained under Uday Shankar, danced across continents, lit up India’s early cinema and theatre, and later, with her sharp tongue and sharper memory, stole every scene she ever walked into — even at 102, when she last breathed. She loved poetry, performance, a good laugh, and above all, being seen. “You’re looking at history,” she once said to her daughter.

“She was great fun, you know. I could crack all kinds of filthy jokes with her — nothing shocked her. Once, I had to take her for a scan, and when the doctor said everything looked fine, she just turned around and said, ‘Thank God I’m not pregnant!’ That was her — always ready with a line, always full of mischief,” said Kiran Sehgal.

Kiran told her mother’s extraordinary legacy — a visionary dancer, fearless actor, devoted teacher, and unapologetic icon. From performing with Uday Shankar and choreographing early Indian cinema to touring with Prithvi Theatre and shining in British films, Sehgal’s journey was vast and inspiring.

Kiran recalled her mother’s colonial childhood, creative partnership with husband Kameshwar, the turmoil of Partition, and reinvention in London — along with candid, witty anecdotes that revealed her pride and love for performance on and off the stage. Sehgal lived, laughed, and insisted on being remembered entirely on her own terms.

“My mother, Zohra, was fiercely strict — never letting me miss rehearsals or performances. She wouldn’t leave me at home; if there was no school, she dragged me to Prithvi Theatre. As a child, I hated it, but she insisted I join the dance classes she led on stage. The theatre was her world — of struggle and joy, sweat and artistry. She was the heart of every play: disciplined, passionate, relentless,” said Kiran, reflecting on how she learned that art demands sacrifice and passion requires discipline.

Marriage and struggles

Kiran’s parents got married in Allahabad during the height of the Quit India Movement, a time of great unrest. Jawaharlal Nehru had promised them Persian carpets as a gift, but he was arrested just a day before the wedding, and no carpets arrived. Due to riots and fear, only one guest attended their wedding reception.

After the wedding, they briefly returned to Almora before moving to Lahore in 1943, still part of undivided India. There, they founded a dance Institute, offering a three-year course with a brochure designed by Kiran’s father. Though tensions arose over leadership, Zohra Sehgal and her husband chose to co-direct.

As Partition approached, the family moved to Mumbai, settling at 41, Pali Hill, Bandra, in a neighbourhood buzzing with artistic energy.

The Anand family — Chetan, Dev, and Vijay Anand — lived nearby, contributing to the creative atmosphere.

“41 Pali Hill was like Disneyland for us kids. There were birthday parties, rehearsals, and so many people from Prithvi Theatre coming by,” Kiran recalled. Their wooden British-era house sat on a hill with gardens and a small junkyard where her father tinkered for hours.

Kiran grew up surrounded by dance, theatre, and childhood friends like Rohan and Anand, the landlord’s sons. Life was full of joy, creativity, and the rhythm of rehearsals, the cultural heartbeat that shaped both her mother’s and her own life.

Also read: Not everybody can learn from MF Husain. Art should be accessible: MAP founder Abhishek Poddar

Passion, pride, and performance

After her husband passed away in 1959, Zohra Sehgal left Bombay, overwhelmed by memories, and moved to Delhi to live with her sister and brother-in-law, both dedicated freedom fighters and communists.

While Kiran’s brother went off to study in Aligarh, she stayed in Delhi, where a vibrant cultural scene was beginning to take shape around Mandi House. Sundari K Shridharani, once her mother’s student and later the founder and director of Triveni Kala Sangam, showed them the bare bones of the Triveni Theatre, dreaming aloud of a future filled with dance, photography, painting, and sculpture. It was only when Kiran returned from England in 1975 that she witnessed Delhi’s transformation into a thriving artistic hub.

During those years, Zohra Sehgal led dance performances for Republic Day parades, co-founded the Natya Academy in 1960 — recruiting talents like Joy Michael and Sushma Seth — and toured internationally in 1962 to Russia, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany. Meanwhile, Kiran stayed with relatives in Delhi, actively engaged in college and dance school.

When the 1962 India-China war broke out, Zohra Sehgal couldn’t bear the thought of leaving Kiran and her brother behind in such uncertain times, and sent them to Canada for safety. Settling at 85, Kensington Road in London, Kiran pursued studies in sketching, drama, and display design, while her mother juggled multiple jobs — stitching curtains, working as a dresser at The Old Vic theatre, and connecting with dancers like Ram Gopal.

Kiran reflected on her mother’s eccentricities and zest for life. “I always wanted to have blue eyes, blonde hair, and a figure 36, 26, 36. I love sex,” Zohra Sehgal once said.

She carved out a stage entirely her own — fearless, unapologetic, and full of life’s contradictions.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)