New Delhi: Sitting in the hall of the India International Centre in Delhi, the audience was taken aback to learn that a vanished pavilion once stood right where they were. Even those who had been visiting for decades had no idea it ever existed.

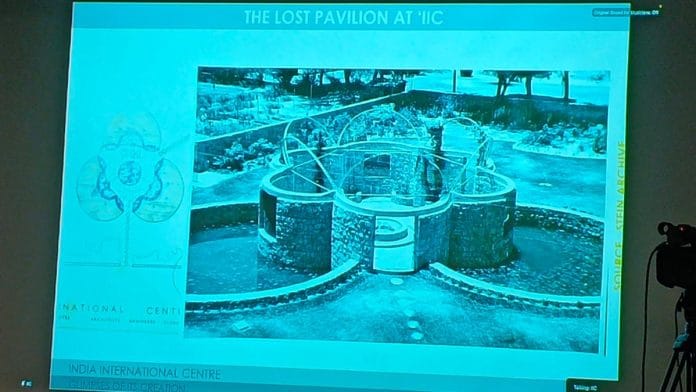

When a black-and-white photo of the missing pavilion and its fountain appeared on the projector screen, questions filled the room: “Where was it? How did it disappear? Why hasn’t anyone rebuilt it?” But architect Ravi Kaimal, who was leading the discussion on the IIC’s history, left the mystery hanging in the air.

“Nobody knows where or how it disappeared,” he said.

The event, ‘Living Landscapes: India International Centre and Lodhi Gardens – A Collective Perspective’, held last week, promised insights into the planning and construction of these iconic venues, both shaped by American architect Joseph Allen Stein. But it turned into something more—a rediscovery of forgotten details, including the lost pavilion.

A panel of experts, including photographer and curator Ram Rahman, architect and professor Manoj Mathur, and architect-writer Anuj Srivastava, joined Kaimal in tracing the IIC’s journey from an idea on paper to the institution it is today.

Kaimal kicked off the session with the story of the construction of the IIC. Back in the early planning stages in the late 1950s, the first proposal designated a 2.18-acre plot in Indraprastha Estate for the ICC. At the time, Kaimal said, government architect MM Rana noted that the “frontage would be adequate” for the project—envisioned as a global meeting point.

But Union minister CD Deshmukh and American philanthropist John D Rockefeller III, who spearheaded the project, had other ideas. After visiting institutions like Tokyo’s International House of Japan for inspiration, they brought in Stein to develop the final design.

Initial plans projected the IIC to be larger than its Tokyo counterpart, spanning 45,000 to 50,000 square feet, but Deshmukh wanted something more—a centre that would also be connected with nature. This led to the final site near Lodhi Gardens for its aesthetic and practical benefits.

“When you think of the IIC’s current location today, it’s hard to imagine it anywhere else,” Kaimal said.

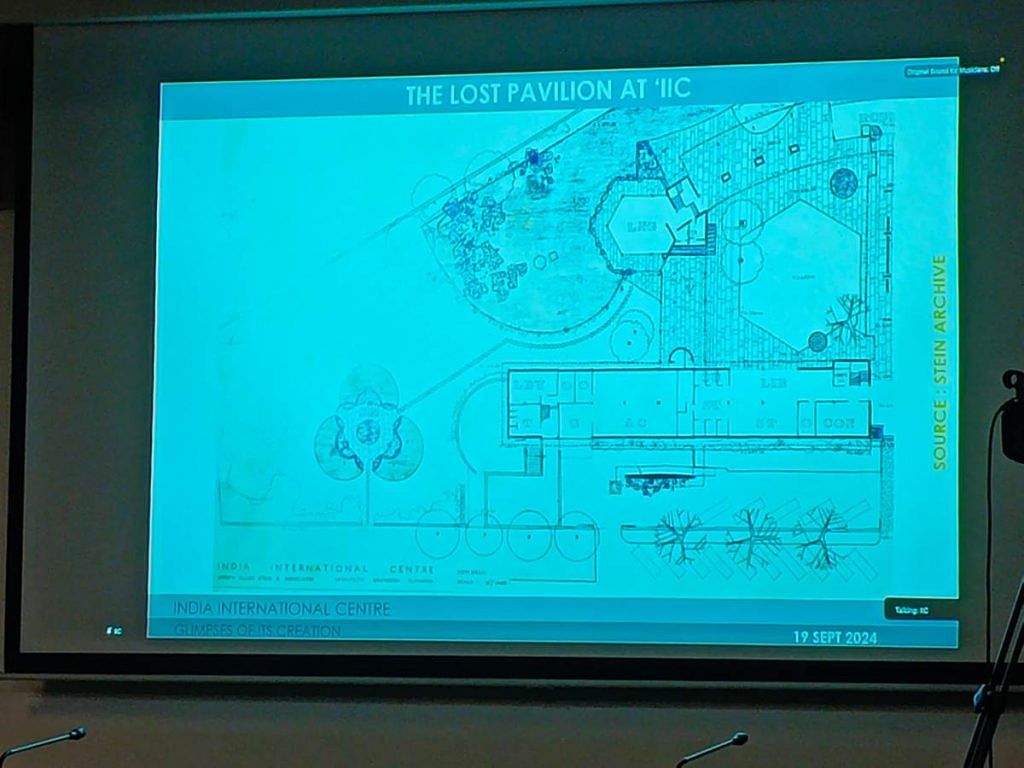

He then presented original design sketches of the IIC’s hexagonal hall, pointing out its intricate details, from the ceiling to the tables.

“I often share this with the next generation—computer natives—showing that you don’t need a lot of technology to create a highly expressive drawing that conveys diverse information, from roof details to floor seating,” Kaimal said.

Also Read: A history of Delhi’s favourite park—Lodi Gardens

‘Building in a garden, or gardens in a building’

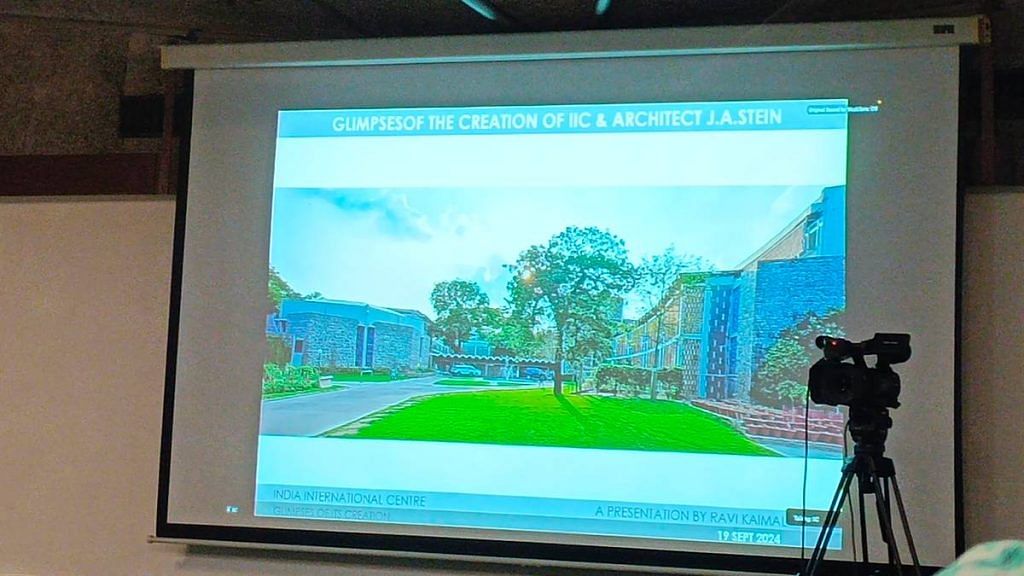

The gardens of the India International Centre are as much a part of the building as the walls themselves, connecting the architecture with the natural environment. The gardens have evolved over the years, much like the discussions held within the IIC’s halls.

“This is a building in a garden and a garden inside a building,” a voice from the audience remarked.

To this, panellist Manoj Mathur, a professor at the School of Planning & Architecture, pointed out that when nature and design are brought together with the right vision, it enhances the experience of that place. He gave the example of Lodhi Garden.

“As a young boy, in 1964 or 1965, I often found myself wandering through Lodhi Garden, captivated by the seamless blend of greenery and built form,” he said. “There was a building somewhere, but it was so seamlessly integrated with the garden that even when you walked through it, there were only gardens to be seen.”

Mathur added that during his architectural education, he was struck by how IIC’s features integrated beauty and function—such as in its intricate jali designs.

“These elements serve not only as artistic features but also as practical solutions to architectural challenges, such as deterring pigeons while maintaining airflow and light,” he said.

Mathur went on to say that the IIC’s gardens were “curated” to create a space that felt “alive”. Another audience member chimed in, saying the gardens offer a refuge from Delhi’s bustling streets for visitors.

Also Read: Mehrauli Park conservation is riddled with ownership confusion—needs the Sunder Nursery model

Nature meets history & design

Another living, breathing green space that’s designed to be experienced, not just looked at is Lodhi Garden. Peppered with 15th– and 16th-century monuments, it was initially established as a landscaped garden by the British in 1936 and named Lady Willingdon Park. After independence, it was redesigned in 1968 by architect Joseph Allen Stein—known for his human-centred approach—and given its present name.

“Design shall be dynamic, not static; design shall be areal, not axial; design shall be three-dimensional; people live in volumes, not planes,” read Kaimal, quoting the famous architect Garrett Eckbo to illustrate Stein’s design ethos.

The area around Lodhi Gardens, often referred to as ‘Steinabad’, showcases Stein’s architectural approach, with his imprint on buildings like the India International Centre, Habitat Centre, and the Ford Foundation headquarters.

But Lodhi Gardens is more than a historical landmark—it’s a green lung for the city, a winter picnic spot, and a personal touchstone for many. Panelist Ram Rehman, a cultural activist and architectural photographer, shared memories of his childhood visits.

“I remember that it was a grassy slope going down to this natural water pond where I would sail my toy boats,” he said.

Lodhi Garden is an example of the importance of green spaces in urban environments—places where history, culture, and architecture can come together to create something lasting.

Reflecting on Stein’s contributions, Rehman added: “Gardens are not just places of beauty; they are living narratives of our shared humanity. The intimacy of families and architecture creates a rare connection that is vital for the spirit of a city.”

With Delhi’s rapid development, speakers at the event voiced concern about the fading presence of visionary architecture in the city—a loss to future generations. Many landmark buildings, along with the stories behind them, have been lost to neglect or demolitions over time, such as Pragati Maidan’s famous Hall of Nations

“While we should celebrate architects like Stein and their visionary contributions, it’s equally important to document and preserve their work,” said Kaimal as the other panellists nodded in agreement.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)