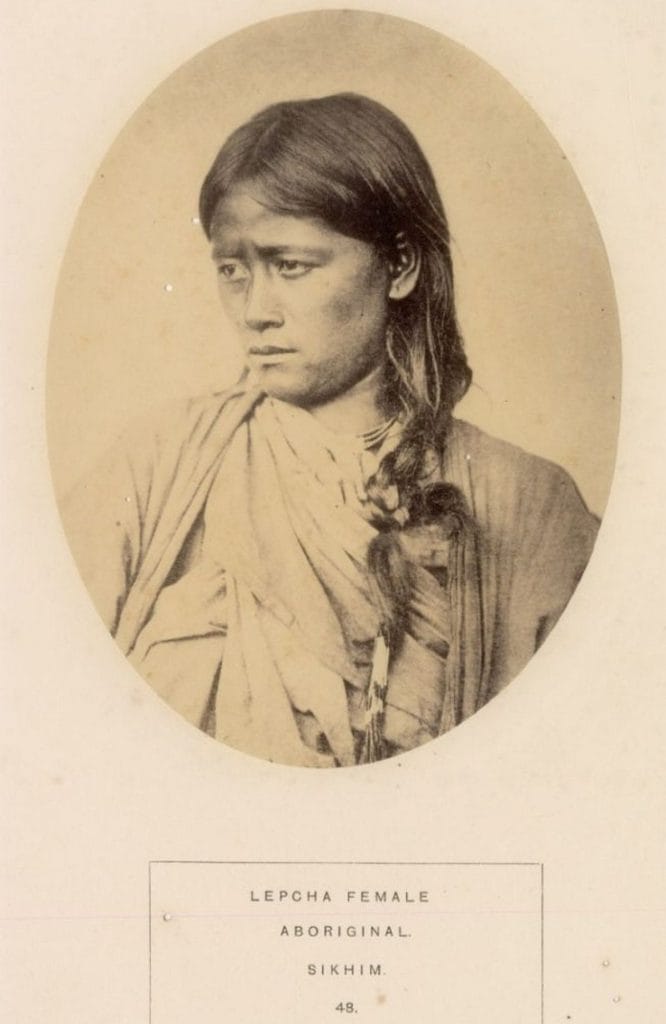

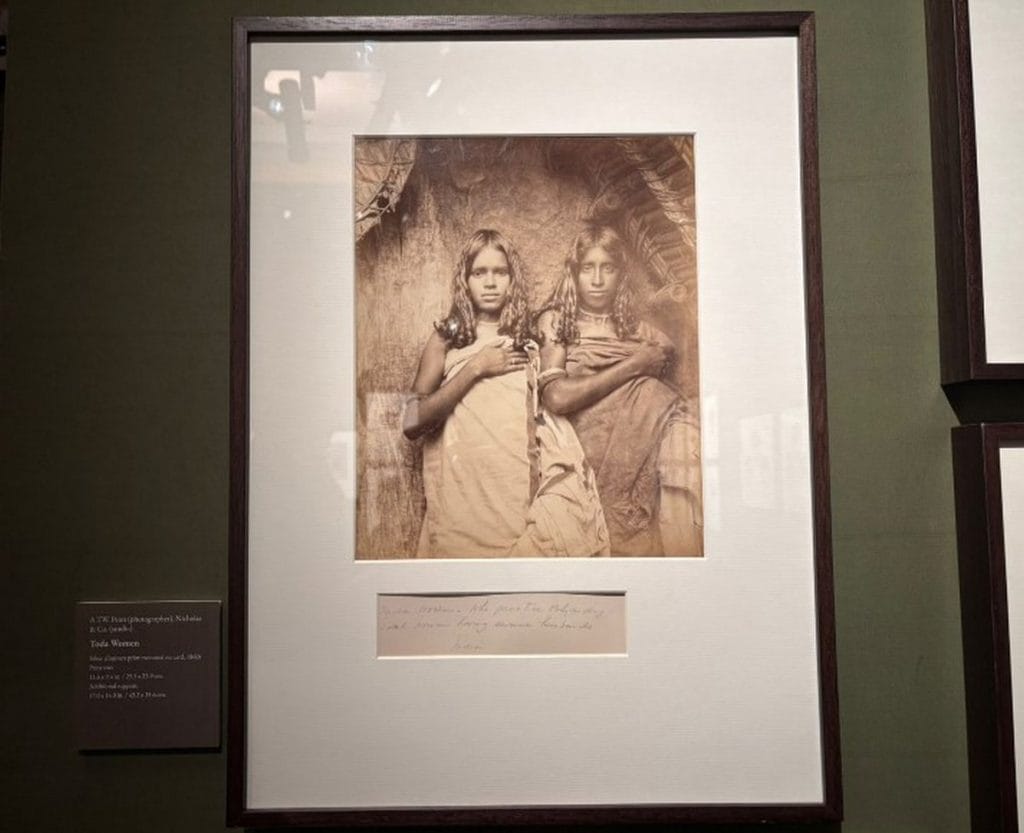

New Delhi: A sweet-maker in Kashmir, a sombre Lepcha woman in Darjeeling, Todas in the Nilgiris. These faces were captured by colonial photographers between the 1850s and 1920s to document ‘types’ for a British audience. Now, retrieved from archives and digital repositories, they are gazing back at viewers in a DAG exhibition.

Visitors move slowly, pausing before each frame. Some read the titles aloud: “Mussulmans of Bhopal,” “a Marwaree man,” “a Naga woman.” This time, the names are spoken with curiosity, not as classificatory labels. Titled Typecasting: Photographing the Peoples of India, the exhibition brings together 166 colonial ethnographic photographs at Delhi’s Bikaner House. Curated by historian and archaeologist Sudeshna Guha and open until 15 February, it asks viewers to confront the act of looking itself.

“These photographs were never neutral, but shaped by aesthetic conventions, colonial priorities, and categories that divided the Indian people into race, caste, tribe and occupation,” said Guha.

In the mid-19th century, photography and colonial anthropology were almost twin disciplines. Anthropologists at the time, preoccupied with racial types and stratification, used the camera for ‘scientific’ classifications of people. The exhibition includes works by John Edward Saché, Lala Deen Dayal, Oscar Mallitte, and S Hormusji, mapping communities across the subcontinent — from Bhutias in the northeast to Afridis in the northwest to Veddas in the south.

While the medium was used to present dancers, coolies, barbers, and snake charmers as fixed types, Guha pointed out that these images also resist being locked into that frame.

“Those photographs open many histories, and therefore they’re irreducible to ideological contexts,” she added.

Also Read: India Art Fair shows ecology is no longer an abstract anxiety in Indian contemporary art

A colonial gaze

The photographs on display include cabinet cards, cartes-de-visite, albums, postcards, and folios that were shot in a style that echoed earlier East India Company paintings. They were collected, traded, and sent back to Europe as proof of having “seen India”.

The exhibition draws from an archive that DAG has built over the last decade, now one of the largest collections of early photography in India.

“Photography, invented in 1839, was in widespread use in the field by the mid-1850s across the globe. This is precisely the period when anthropological study really began as the earliest academic venture in South Asia, in the years after the uprising of 1857,” said Guha.

From the 1870s, the camera became central to anthropology. Tribes and communities were photographed as evidence. Frontier groups were framed as violent; others as “martial races”. Field photography and census surveys turned images into proof of scientific authority.

The exhibition also traces how photography in colonial India put people into categories by work, community, and gender, solidifying social and economic hierarchies. Images of shopkeepers, boatmen, tea-pickers, barbers, potters, and cooks presented labour as identity, linking trade to caste.

“It portrays very much a colonial perspective on Indian society, and they were meant to be viewed and seen and used by Europeans. So we have bought them and walked them back to India,” Guha said. “I think it’s for us really then to question some of the categories, or some of the perceptions that these photographs give us, whether it’s snake charmers or the dancing girls.”

The women’s portraits, especially, sit uneasily between documentation and spectacle. Nautch girls and “beauties” circulated as attractions. Offsetting this, the exhibition also included works by Indian photographers— such as Darogha Abbas Ali, known for his Beauties of Lucknow (1874) series— which resisted colonial typology, using the camera to represent rather than classify culture.

Also Read: Red bricks from demolished homes and the burden of identity at India Art Fair

A portrait’s many faces

Walking through the exhibition, Guha repeatedly returned to a central question: When does an ethnographic image become a portrait?

She resists reading them only through the colonial gaze. These images, she argues, contain acts of self-fashioning.

Stripped of captions and classificatory frameworks, many photographs reveal unexpected agency. The label does one thing, the subject defies it. A “high caste Brahmin girl” looks straight at the camera. A “Marwaree dancing girl” exudes dignity.

“A family portrait can become racial evidence, when placed under the ‘Races and Tribes of India’,” said Guha. “The same image can shift meaning entirely, depending on its use.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)