Mumbai: Mumbai is not done with the underworld. It has simply transitioned into a new era, said Rakesh Maria at the launch of his new book, When It All Began. A fresh generation of gangsters, exemplified by figures such as Lawrence Bishnoi, operates very differently from the city-rooted dons of the past.

“Today’s players are more educated, tech-savvy and remotely connected, making them harder to track and far more dangerous. They no longer need to reside in the city to command it; instead, they run operations from afar, with access to wider resources, international links, and digital tools. The old underworld was visible and territorial, but the new one is dispersed, fluid, making it harder to pin down,” Maria told ThePrint.

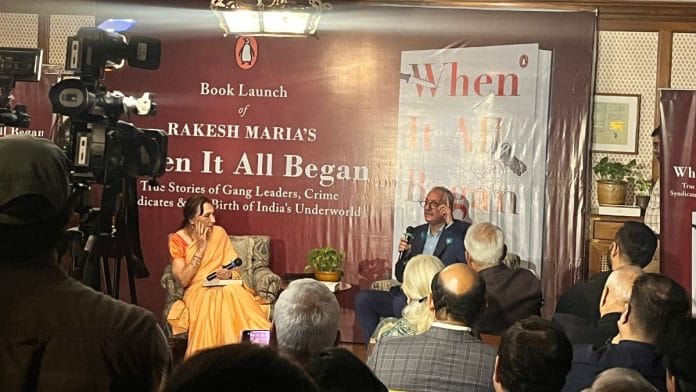

He was speaking at Soho House in Mumbai’s Juhu on 28 November. The event featured speakers from the police forces, such as V Balachandran, Deputy Commissioner of Police Bombay (present-day Mumbai) in 1972, Satish Sahney, Commissioner of the Mumbai Police (1993-1995), MN Singh, Commissioner of Mumbai Police (2000-2003), and Dr PS Pasricha, Commissioner of Mumbai Police (2003-2004).

Also present at the launch were directors and actors from the film fraternity, including Mahesh Bhatt, Nana Patekar, Boney Kapoor, Rohit Shetty, and Ajay Devgn. The latter part of the evening featured a conversation between senior journalist and writer Sathya Saran and Maria.

With 38 years of research on the job, Maria presents the rise of the underworld, tracing their origins in the 1930s, their entry into the city’s crime circuits, and the forces that moulded them.

“I have seen in him amazing qualities, elephant memory… And the micro details of the criminals, the mafia, and the way he has traced the history from the 1930s to the 1980s [in the book] is commendable,” said PS Pasricha, former Mumbai Police Commissioner.

Shetty shared a fun anecdote at the launch, revealing that during his force days Maria was nicknamed ‘Marie Biscuit’.

“When shooting this film or going through the script, it’s all the characters, even the havaldars’ [constables] names, he has. And we had to cast around 580 people because of each and every detail he had, and [he] gave credit to everyone,” he said.

In the book, each don emerges with nuance: their childhoods, their codes, their ruthlessness, and their vulnerabilities, all laid out for the reader.

“When he introduces Karim Lala [in the book], I cannot help seeing the human side in him when he rescues that girl who is being beaten by that drunk guy. And not only does he save her, but he gives her custody. Asks her to live in his home. When word gets around that he is violating her, he marries her,” Bhatt said.

In When It All Began, Maria traces Karim’s life all the way back to his adolescence in Peshawar, revealing how he started out as a righteous man who strongly opposed corruption.

“They were gangsters. But you explored the human side of even those violent, brutal men,” Bhatt said to Maria.

From traffic to crime

Through decades of service, Maria maintained diaries recording every meeting, source, and every gangster’s crossing in/out of a life of crime. Police work for him is inseparable from meticulous documentation, observation, and discipline.

That preparation found its real test in 1993.

Mumbai shook on 12 March 1993 as 12 explosions ripped through the city. Maria was then Deputy Commissioner of Mumbai Police Traffic, managing barricades and diversions—nowhere near what would soon become the most defining investigation of his life.

The following day led to a breakthrough: a Bajaj scooter was traced as a key feature in the blasts. That evening came the call that altered the arc of Maria’s career: a summons to the ‘King’s Office”. He was called into the office of AS Samra, Commissioner of Mumbai Police at the time. Inside, MN Singh, who was Joint CP at the time, handed him a mandate to form a team and investigate the blasts.

“First thought that crossed my mind when I was asked to form a team after the blasts was actually a feeling of fear as a result of the responsibility that fell upon me, with high expectations of my seniors and the safety of the people of this city, and of my colleagues in the force,” Maria said.

By November 1993, the chargesheet was filed, and not long after, Maria discovered that crime detection was his true calling.

On 13 December 1993, he was appointed DCP Crime Detection, a role that pinned him to the heart of Mumbai’s crime policing machinery. Then came 1998, when Mumbai was burning with the heat of underworld wars. He was appointed Additional CP Crime for the Northwest region—Bandra to Borivali (two separate additional city regions now), which was then ground zero for extortion rackets, shootouts, and gang rivalries.

Also read: Indian-born scientist wrote to Obama on fossil fuel lobby. Fox News called him dangerous

Supari killings: the dog and the don

The first supari—contract killing—recorded in the Mumbai underworld was in November 1969, Maria said. The attempt on Yusuf Patel’s life in Mumbai’s Paidhuni was a supari given by Haji Mastan from the Arthur Road Jail. Karim Lala was given the supari to kill Yusuf Patel, for which he received Rs 2 lakh and two Fiat cars.

Contracts in Mumbai were no longer just gang orders; they were business transactions. It marked a shift from personal vendettas to professional assassinations—a colder, more calculated phase of Mumbai crime.

Among the many supari cases Maria encountered during his research for the book, one stood out for its cruelty and cunning.

It was the killing of Abdul Majid, son of Dilip Aziz. The brothers, Abdul Hamid and Abdul Majid, had been marked for death by Pathan gang leaders Rahim Lala and Abdul Rehman Lala. The Aziz brothers were found scheming to kill Rahim.

Hamid was already in Arthur Road Jail, so the Pathans decided to take out Majid. They gave the supari to Ejaz Pathan, who hired Munna Bhanwanlal Gupta to get the job done. Majid, aware of the threat to his life, found that the safest place for him was his own house. Whenever he stepped out, he was surrounded by bodyguards.

At home, he had a ferocious German Shepherd. The loyal dog would not let any stranger close to his master. A trusted servant of the household would take the dog out for a walk, and that’s where Munna saw his chance. He befriended the dog by regularly feeding him biscuits and even had daily interactions with the servant.

Munna rang the doorbell on 28 April 1986, and the dog reached the door, wagging his tail. Seeing this, the servant opened the door. Munna fed a biscuit to the dog who had come to love him and then shot him dead. Immediately after, he executed Majid.

“This, for me, was the most exciting of all suparis as it showed creativity and methodical precision,” said Maria.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)