Mumbai: As Mumbai kicks off the Gallery Weekend 2026 from 8-11 January, the DAG’s latest exhibition at the Taj Mahal Palace turns the spotlight on the faces that have quietly shaped the city’s long and layered history. Face to Face: A Portrait of a City brings together thirty portraits from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, using the genre of portraiture to trace Mumbai’s evolving social, cultural, and political life.

The exhibition chronicles the development of portraiture in Bombay from the introduction of academic realism through colonial institutions to the experimental approaches of India’s modernists. With the establishment of art schools such as the Sir JJ School of Art in Mumbai, European techniques of naturalistic representation gained prominence, influencing both artistic practice and patronage.

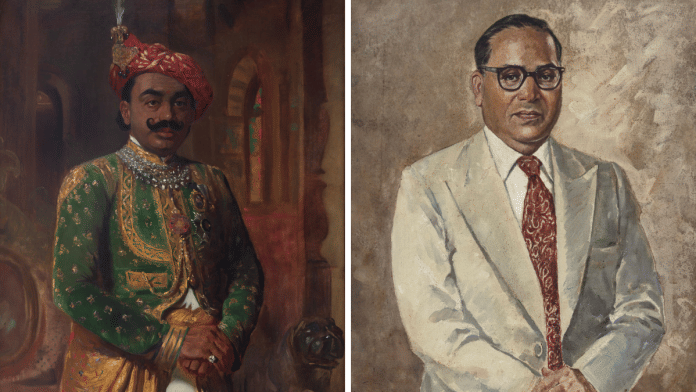

The exhibition is curated to showcase princely figures such as Jaswantsingji Fatehji and influential personalities BR Ambedkar and Bal Gangadhar, who signal authority and aspiration. The Parsi community, whose philanthropy and enterprise are integral to Mumbai’s civic imagination, and artists’ self-portraits that reflect changing ideas of selfhood and modernity. Anchoring these narratives are portraits of everyday Mumbaikars, grounding the city’s grand histories in lived experience.

Together, the works displayed aim to show how portraiture in Mumbai was never just about likeness – it was a record of shifting hierarchies, emerging communities, and evolving artistic practices.

“Portraiture, quite literally, puts one face-to-face with people as its subject, and these people’s lives are inextricably linked not with just the city but with the Presidency represented through these portraits,” Ashish Anand, CEO and Managing Director of DAG, formerly Delhi Art Gallery, told ThePrint.

Also Read: How Mumbai grew—and became crowded

Power, Community and Change

One of the earliest works on view – Frank Brooks’ striking 1892 portrait of Jaswatsingji Fatehsingji, Thakur Saheb of Limri – exemplifies this moment. Brooks, a famous British painter, travelled to India only twice. During his second visit (1892-93), he was commissioned as part of a series marking Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee to paint portraits of twenty-eight rulers of the Kathiawar agency in Gujarat.

His portrait of Jaswatsingji Fatehsingji blends academic realism with Indian courtly visual codes, offering insight into early colonial representations of regional power. Brooks’ significance is further underscored by his role as teacher to Raja Ravi Varma’s brother, placing the work firmly within the genealogy of Indian art history.

“Historically, it (the exhibition) includes artists from the West, such as Frank Brooks, who was specially commissioned to paint portraits of the Kathiawar princes; and Cecil Burns, whose work is closely associated with Sir JJ School of Art,” Anand said.

The exhibition also shows how Bombay’s portrait tradition gradually loosened its formal constraints. Self-portraiture by artists such as Baburao Sadwelkar marks a moment of transition. While trained in academic realism, Sadwelkar, with his art, embraced intuitive and individualised modes of expression, anticipating the emergence of modernist sensibilities in mid-twentieth-century Bombay.

“An exhibition such as this permits a glimpse into history that brings with it an element of exploration and curiosity, however fragmented or comprehensive that may be,” Anand added.

This shift is most striking in the exhibition’s section on artists’ self-portraits, where works by Sadwelkar, MV Dhurandhar, Pestonji Bomanji and Sawlaram Haldankar reveal how artists negotiated identity and authorship within a changing cultural landscape. For them, the self-portrait was both a demonstration of technical mastery and a declaration of status within a colonial art world.

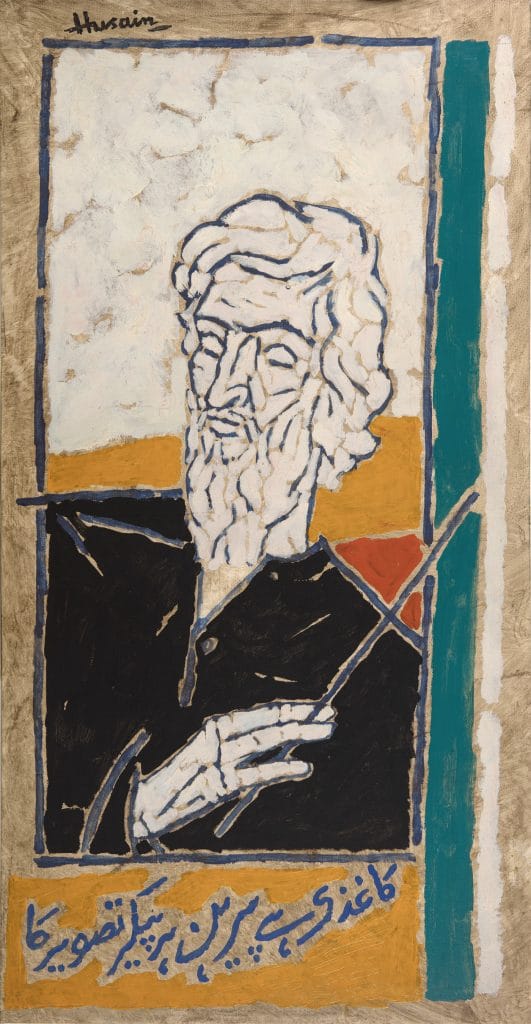

By contrast, MF Husain’s self-representations, through his self-portrait, reject realism altogether, collapsing the boundary between the artist and his public myth. Fragmented, symbolic and performative, the self-portraits by these artists together reflect a post-Independence reimagining of portraiture as psychological and expressive rather than descriptive.

For Anand, the exhibition offered the most fascinating curatorial possibilities.“One of the more delightful elements of this particular selection is a group of artist portraits and self- portraits brought together for the first time on such a scale. This includes self-portraits by artists such as Dhurandhar, Bomanji, Haldankar, Baburao Sadwelkar, Husain, and VA Mali’s portrait of Baburao Painter,” he said.

Also Read: Redefining Mumbai for Delhiites—how Chef Ajay Chopra’s SoBombae surpasses expectations

Faces that Shaped ‘Bombay’

The exhibition, which features 20 known and 1 unknown artists, also foregrounds figures whose influence shaped Bombay’s political and cultural life. VB Pathare’s portrait of BR Ambedkar anchors the jurist and social reformer within the city’s intellectual milieu, reflecting his deep ties to Bombay – from his education at Elphinstone College to his role in the Bombay Legislative Assembly.

Ambedkar’s presence underscores the city’s importance as a site of reform, debate and public leadership. Portraits of figures such as Bal Gandharva, the legendary Marathi singer and theatre actor, recall Bombay’s vibrant performance culture and its role as a centre for artistic and social imagination.

Anand went on to say, “While it (the exhibition) is a rich evocation for art historians as well as art-lovers, there is much that historians or those from other walks of life will find extraordinary. Two examples should suffice: Dhurandhar’s portrait of Bal Gandharva and Pathare’s portrait of Ambedkar, which represent key figures from vastly different fields – one celebrated as a theatre artiste, the other as the one who framed the Constitution – both, ultimately, residents of a city that helped create as well as celebrate their identities.”

Equally central to the exhibition is the role of the Parsi community in shaping Bombay’s civic and philanthropic life. A portrait of Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy by Dady, India’s first baronet, depicts him in traditional Parsi attire, symbolising a legacy of generosity that continues to define the city’s institutions, from hospitals and schools to public infrastructure.

Complementing this is MF Pithawalla’s portrait of a Parsi woman, which illustrates how portraiture became a means of self-fashioning within the community. At a time when Parsi women were increasingly visible in civic and cultural spheres, such works projected confidence, modernity and social standing, positioning the community – particularly its women – as progressive and integral to colonial Bombay’s public life.

Beyond elites and icons, the exhibition also gives space to portraits of everyday Maharashtrians, spiritual figures like “an old fakir” & “an elderly gentleman”, revealing how the city’s history is sustained by memory, labour and faith. Works by artists such as Abalal Rahiman place regional rulers and local communities side-by-side, offering visual insight into distinctions of occupation, status and self-presentation within.

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)