Hyderabad: A stone pillar flipped on a scrubby hilltop in Telangana led to the discovery of the date of death of a significant queen of the Kakatiya dynasty. It was inscribed around 700 years ago on a much older Buddhist pillar dating back nearly 2,000 years.

“We turned it upside down and found Queen Rudramadevi’s death inscription, her exact date of death is written,” said Sanathana YS, Director (Research & Projects) of the Pleach India Foundation. “Because of our Preserve Heritage for Posterity programme, this came to light.”

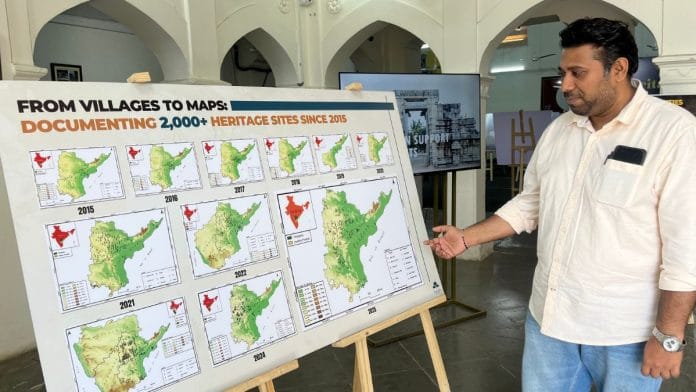

Material and photos of artefacts discovered as part of the Preserve Heritage for Prosperity (PHP) was displayed in an exhibition at the History Literature Festival Saturday.

Pleach is a Vijaywada-based multidisciplinary group of about 20 historians, archaeologists, designers, and media professionals who bring archaeological history and findings to common people through digital media, offline talks, and online webinars. They mainly examine sites that are excluded from the state lists or by the Archeological Survey of India.

“Our core idea is that a lot of excavations and research are happening—whether on the Indus Valley Civilization or elsewhere—but that knowledge is not reaching the common man. What people are getting instead is fabricated or exaggerated history. Authentic heritage knowledge is not reaching them,” Sanathana said.

Also read: An Arya Samaj leader suggested adding a charkha to the Indian flag

Ancient artefacts in everyday settings

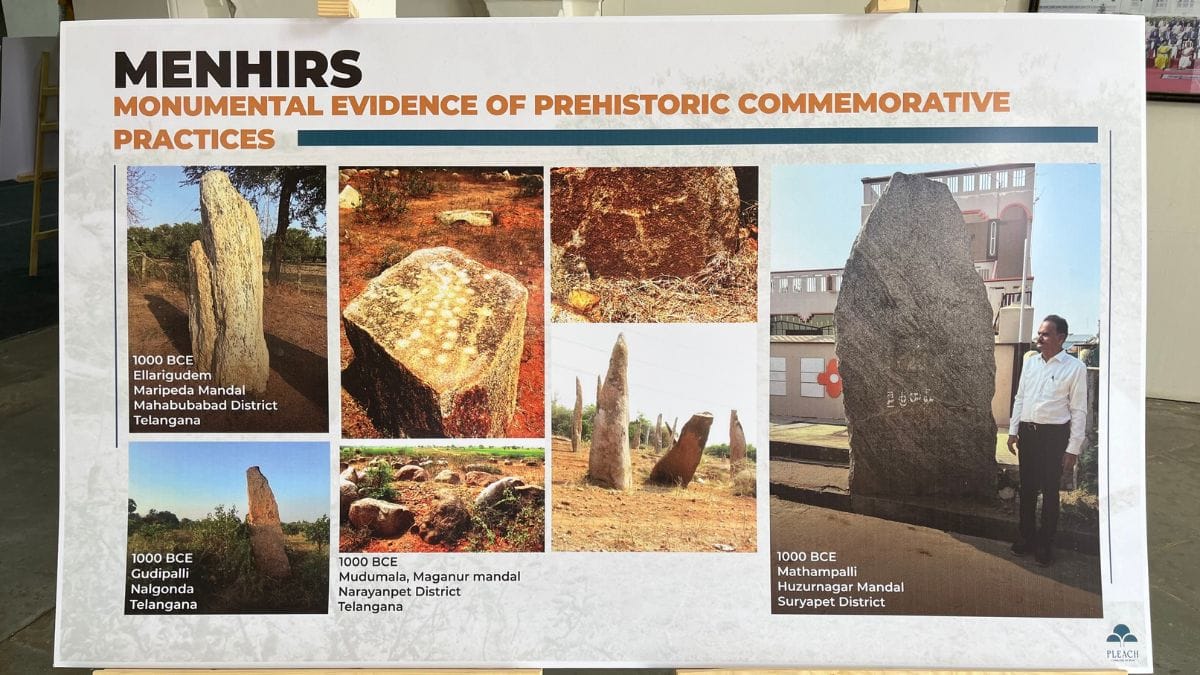

Led over the past decade by CEO Emani Sivanagi Reddy, a former director with the Telangana and Andhra Pradesh State Archaeology Department, PHP has taken teams into villages across the two states to document unprotected sites. These range from ruined temples and stepwells to rock-cut caves, prehistoric habitations, fort remains, and sculptural fragments.

“Our main intention was to sensitise local communities, not just to document. But gradually we gathered so much data, geocoordinates, site typologies, estimated time periods, we now have a large database,” said Sanathana.

Some of the most striking examples come from everyday settings. In one village, two Jain sculptures with inscriptions were being used as part of a makeshift water barrier. Elsewhere, Buddhist deities lay on a lake bank. “They [villagers] know these are gods, but they don’t know these are nearly 1,000 years old. We are making them realise their village history is that old.”

Telangana’s Buddhist past emerged as a recurring theme. “We found an image of Buddha in Bhumisparsha Mudra, touching the earth, and alongside it a depiction of Vajra,” a team member pointed out. “That is a symbol of Vajrayana Buddhism. These findings indicate Telangana was a very important centre of Vajrayana.”

Out of more than 2,000 documented sites, only 40 are displayed in the exhibition. One such artefact was found at a tea stall. “Sir [Reddy] was touching the centre post and felt intricate carving,” Sanathana added. “It turned out to be a sixth-century Buddhist pillar.”

After villagers were told its age and significance, they installed it on a pedestal at the village entrance; it was later moved to a district museum in Eluru.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)