New Delhi: When Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi requested a supercomputer for India in 1987, US President Ronald Reagan handed him a puny version of it. The Cray supercomputer was meant to power monsoon research.

“Americans sold, at full price, a very ordinary computer, and India paid a huge price. But I am told that it was necessary to get other technology agreements done,” said Jagdish Shukla, meteorologist and Professor Emeritus at George Mason University.

The incident happened before India built its own supercomputers. Among the technology agreements negotiated during this time was an agreement on transferring American technology to build an Indian Light Combat Aircraft (LCA). The LCA was finally inducted into the Indian Air Force in 2019, after 32 years and many changes.

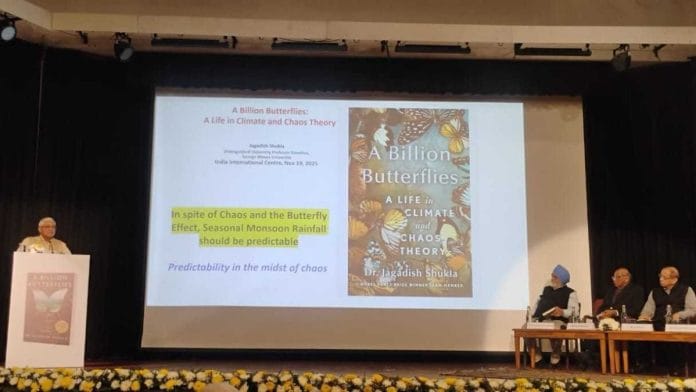

Shukla made the comments during the discussion of his memoir, A Billion Butterflies: A Life in Climate and Chaos Theory, at the India International Centre, Delhi. Former Deputy Planning Commissioner Montek Singh Ahluwalia and former cabinet secretary Ajit Seth participated in the discussion, which was moderated by former foreign secretary of India Shyam Saran. Weather researchers and academics made up the audience.

Shukla’s book traces the journey of a boy from Mirdha, a small village in Uttar Pradesh, through BHU, MIT, Princeton, NASA, and George Mason University to become an authority on seasonal weather prediction. “The chaos in the title does not refer to just the monsoon, but also the chaos in my personal life,” Shukla said.

Shukla is one of the 450-odd lead authors of the Fourth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which definitively established that global warming is a concern warranting international action. The IPCC got a Nobel Prize in 2007 for the work.

Shukla was in charge of setting up the supercomputer and running Indian weather observations data through it, the only Indian-origin person to have access to the room housing the device at the National Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (NCMRWF). As a senior scientist at NASA working with supercomputers on his weather experiments, Shukla was the perfect intermediary between the supercomputer staff from the US and Indian weather researchers.

The Cray X–MP 14 came with many humiliating conditions for its operation and ‘security’. The housing facility needed to be secured by high fences and layers of rifle-wielding guards. Only Cray employees and American citizens could go into the room with the computer.

The ostensible reason for these stipulations was the possibility that the supercomputer would be used in India’s nuclear research. However, CIA documents declassified in 2012 show that the US was eager to prevent its advanced technology from reaching the USSR via black markets.

“It was all politics. Reagan wanted to give the computer. But the security agencies tried to deny it to India,” Shukla said.

Ahluwalia cited two reasons that helped the Americans shed their reluctance. One was that Rajiv Gandhi got the CDAC to start working on building India’s own supercomputer, which would later become PARAM. The other was that the particular Cray computer model was getting old.

Ahluwalia recalled that before 1989, the weather forecasts were unreliable. “In a presentation made to PM Rajiv Gandhi, a group of scientists used regression-based models based on a few variables,“ he said.

He thought, at the time, that the models were mere statistical associations. “I now understand better. Without the kind of computer that was obtained, we could not have further models,” Ahluwalia added.

Climate change activism

Moved by the climate scepticism pushed by interest groups in 2015, Shukla wrote a letter to President Barack Obama stating that the fossil fuel lobby in the US was preventing action against climate change through paid research and other means. He advocated action against such groups under racketeering laws. Shukla immediately came under attack online and in the media, where he was said to be trying to criminalise dissent.

Prominent TV hosts such as Tucker Carlson and Bill O’Reilly were riled up. In A Billion Butterflies, Shukla writes that Fox News branded him the third most dangerous person of 2015.

“I was attacked. I was intimidated. I was harassed. They said ‘Go back to India,’” the meteorologist said. Federal investigations followed. Ironically, the Chair of the House Committee on Science was himself a climate sceptic, and opened a Congressional investigation against Shukla and other scientists who advocated government action on climate change.

Shukla admitted that even he was initially ambivalent about the climate change issue, and turned into an advocate only after he convinced himself that the evidence was clinching.

“Unless you have already determined that climate change is a hoax, [climate science] is easy to understand,” he said.

For Shukla, the 2015 Paris conference was a moment of hope. Everyone at the event understood the gravity of climate change. And then the elections happened in 2016, bringing Donald Trump to power.

“I was at the Paris conference. Nobody had any problem with the science of climate change… It is only after we go back, and there is an election, and the US president says climate change is a hoax.”

At the time, the argument of climate sceptics was that global warming was merely due to changes in the sun’s cycles or volcanic activity.

Bhavleen Rekhi, a professor of Digital Marketing, asked Shukla whether AI can be incorporated into weather forecasting. His answer surprised the audience.

“Everybody talks about AI. There is a difference between AI models and physics-based models. Physics-based models use mathematical equations and laws of physics. AI models don’t know anything about physics. But they are doing as well as physics-based models,” he said.

This is striking because AI models usually struggle with large, complicated chains of calculations.

“The difference is that the AI models use 70 years of initial conditions to predict weather, and physics-based models can do with one day of initial conditions,” Shukla added.

AI models can’t help us understand how the weather works, but over a long period of time, they can ingest observation data and give reasonable predictions. According to Shukla, the best approach would be a hybrid of AI and physics-based models.

Both AI and physics-based models are computer programmes. One may imagine that the vast hardware infrastructure developed in the AI race, such as GPUs and processing accelerators, could be useful for improving weather forecasts. The only problem, however, is one of practicality.

“There are practical difficulties. Personnel trained in high-performance computing have been coding software a certain way for a long time. Moving all that work into new programming models to work on AI accelerators is a lot a work and will take time,“ Shukla told ThePrint.

Also read: We live in a strange democracy where the world is led by undemocratic UNSC: former Lesotho PM

Tough times for Indian expertise

Ahluwalia noted that Shukla’s journey is inspiring for every child in the Indian heartland. He urged Shukla to release a Hindi translation of the book. “The reach is much larger. All the English-speaking people, in any case, think very highly of themselves,” he said.

Indian scientists and researchers must have more direct contact with their colleagues abroad, Ahluwalia added.

“Shuklaji was able to work at MIT and Princeton because he went there on a scholarship. Now, what the Chinese are doing is they are sending them on government money. It is not good enough to rely on scholarships,” he said.

As funding for universities in the US comes down under Trump administration, the first sufferers turn out to be Indian students on scholarships. “If we want high quality scientific work in India, we must make absolutely sure that younger people get a chance to go abroad,” Ahluwalia said.

According to Ahluwalia, there is another problem with Indian research. He described an instance where an IIT Ropar researcher invented a device that could be hung around a cow to determine the best time for the animal’s artificial insemination. The device would then send an SMS to the farmer.

When Ahluwalia asked the researcher whether he had exchanged views with agricultural universities, he learned that researchers from the Punjab Agricultural University could not visit other campuses easily. Every time they want to visit Ropar, 40 km away, they have to take permission from their director.

“It’s not just money. We need a lot of that. But frankly, we need to tear up the regulation of all our research institutions and universities,” he said.

Ahluwalia also has something to say about the Indian leadership dealing with the current US administration. He recalled the Indo-US nuclear deal talks. At the time, many in the US administration were opposed to the deal. Ahluwalia quoted Samuel Bodman, then US Energy Secretary: “We don’t actually agree with what the President (George Bush) is doing. But he has given me a direction.”

Ahluwalia sees a lesson in the incident.

“If you want to change the bureaucracy and get something done, you have to intervene right at the top and decisively. Otherwise, the ability of bureaucracy to kill something should never be underestimated.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)