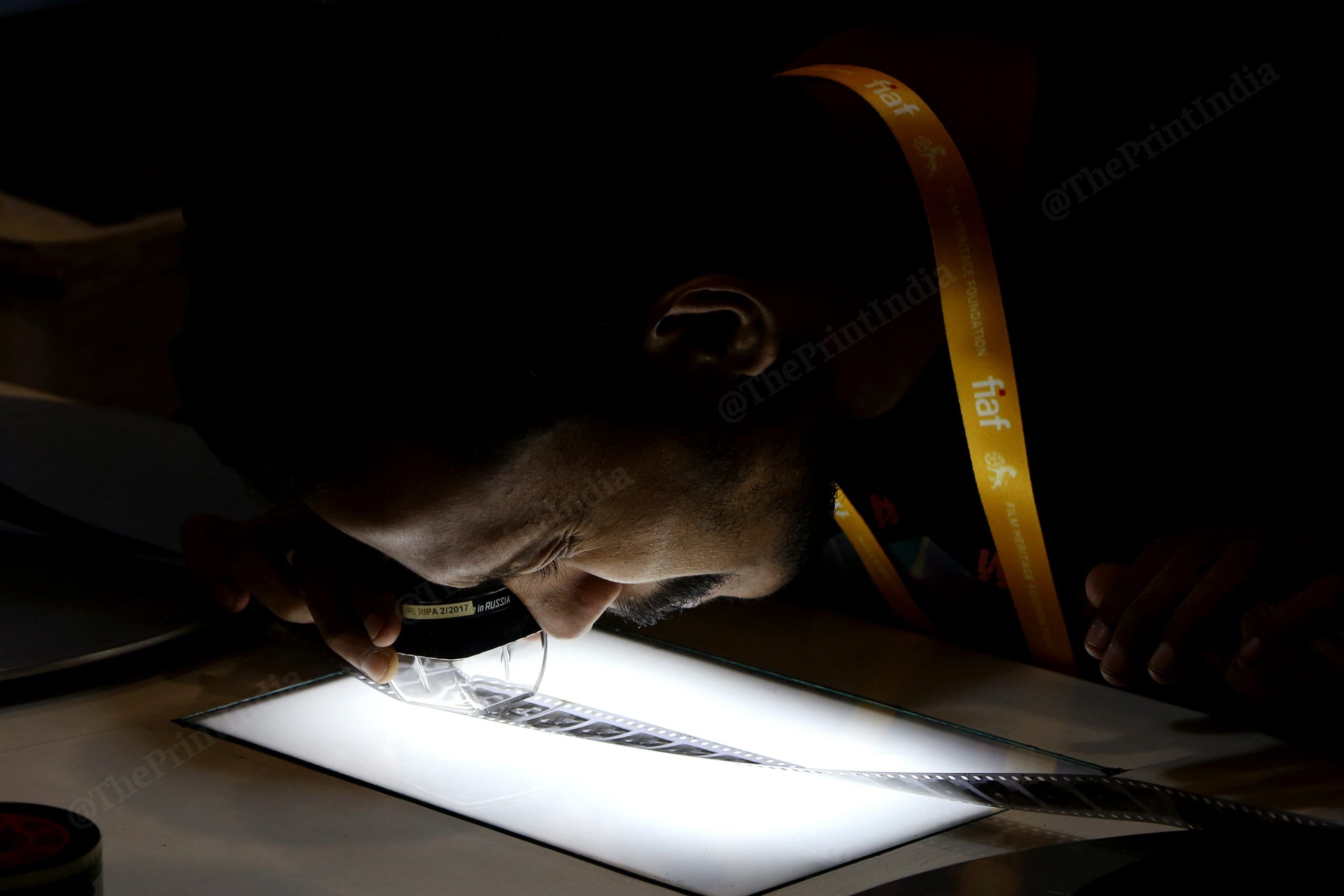

New Delhi: In her white laboratory coat and gloves, Marianna de Sanctis could easily pass off as a doctor. Six students gathered around a steel table that wouldn’t look amiss in an operation theatre, and watched her every move. She carefully opened a 35mm film canister and methodically unspooled the reel onto the table. “This is very precise work,” warned de Sanctis.

There’s a sense of urgency—and even desperation—to save what’s left of India’s rich film history.

“It is estimated that by the 1950s, we had lost 70-80 per cent of our films,” said filmmaker and producer Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, who started the non-profit Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) nearly a decade ago.

As head of film repair at the highly specialised restoration laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy, de Sanctis is a doctor—of film reels. The students were part of a 10-day film preservation and restoration workshop at the Biennial Audio-Visual Archival Summer School (BAVASS) 2023, organised by FHF at India International Centre in New Delhi between 10 to 19 September.

The workshops are part of a larger pan-India movement to restore and preserve what’s left of our old reels and digitise them. Under the Narendra Modi government, more than 1,293 feature and 1,062 short films and documentaries were digitised by the National Film Heritage Mission (NFHM). These included the critically acclaimed 1954 Malayalam film, Neelakuyil and the international award-winning Hindi movie Do Aankhen Barah Haath (1957). Earlier this month, around 30 films were restored by the Film and Television Institute India (FTII) in collaboration with the Nation Film Development Corporation of India-National Film Archives of India.

Only 25 reels of the 1,250 films made during the silent era have been rescued and preserved from decay and disuse. The reel of India’s first full-length feature film, Raja Harishchandra (1913), directed and produced by Dadasaheb Phalke, can never be watched again.

By sheer volume, India is among the top film producing countries in the world, but there’s still a severe shortage of technicians when it comes to preservation and restoration.

“In general, and also in India, there seems to be a use and throw culture when it comes to making films. There is no thought that we want to show this film 50 years from now,” said film restorer Robert Byrne who’s been on the board of directors of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for the last 19 years. He was in India to teach a course, ‘Digital Film Restoration: Practice and Ethics’.

Also read: Dagar, Rahman & music in the courtroom—Day 1 of Dhrupad maestro’s fight against film giants

Saving from ruin

Three years after Dungarpur founded the FHF in 2014, it was collaborating with film technicians, experts and institutes to organise preservation and restoration workshops. They were held in cities with a history of filmmaking — Mumbai, Hyderabad and Kolkata. But it is the first time the workshop has been held in New Delhi.

And it was long overdue. The national capital may not have a film industry, but it has been the muse of many movies from Ab Dilli Dur Nahin (1957) and Monsoon Wedding (2002) to Delhi-6 (2009), and Love Aaj Kal (2009).

A life-size poster featuring the evergreen Dev Anand and actor and stuntwoman Fearless Nadia dominated the India International Centre (IIC) foyer in New Delhi. Students gulped down their coffee and snacks before heading for the next classes. Sessions began at nine in the morning, and the day ended with a screening of a restored film in the evening.

Some of the films restored by FHF that were screened were Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now-Final Cut (1979), Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992), G Aravindan’s Malayalam-language film Kumatty (1979) and Ridley Scott’s Thelma and Louise (1991).

In one class, de Sanctis showed students how to clean reels and repair cuts with the help of clear polyester tape. Old and deteriorated nitrate films are so flammable that they can even burn under water. She demonstrated how to open the canister while positioning the body away from the reel just in case toxic gases have collected inside.

The workshop brought together around 50 participants, from 13 African countries, Asia, Europe, Australia, South and North America. Students are taught to identify reels by the size, understand the ethics of film preservation, and various aspects of archiving. Faculty from all over the world—British Film Institute, Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum, German Federal Archives and International Federation of Film Archives—are part of this initiative.

At Rs 52,700, the course is not cheap, but the foundation collaborated with Tata Trust to offer scholarships to 27 out of 51 students this year.

Aboubakar Sanogo, an associate professor at the film studies programme in Carleton University in Ottawa, took leave from work to attend this workshop. Restoration of reels is just one part of the process. To preserve the films, the reels have to be stored in temperature-controlled rooms (at as low as one-degree Celsius temperature) with little exposure to the air. But film preservation, Sanogo argues, is still by and large, a Euro-centric practice.

“Even the technology of film preservation needs to change. In most African countries, you hardly have a full day of electricity. How do you preserve films with four hours of load shedding?” said Sanogo, who is also the North American Regional secretary for the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) and he was also a jury member at the International Film Festival of Kerala in 2017.

He suggests traditional methods like using adobe blocks that are used to build houses in many African nations due to their naturally cooling effect. “These are not necessarily methods people in the West are aware of. That must change,” said Sanogo. A big fan of world cinema, including Shah Rukh Khan’s movies, Sanogo hopes to contribute towards the African Film Heritage Project (AFHP).

Closer to home, Prasant Kumar Mohakud, who works at Odisha State Archives in Bhubaneswar, has attended three of these workshops so far. Odisha does not have a film archive, yet, and Mohakud wants to change that.

“Every year, around 20-200 [Odia language] films are produced in the state, and nearly 1,000 films are in a precarious condition because of damage,” said Mohakud, who won a scholarship from the Tata Trust to attend the workshop.

“We have already lost the first Odia film Sita Bibaha, made by Mohan Sundar Deb Goswami in 1936. I don’t want more films to be lost,” he said.

Also read: Love stories of British men & Indian women in colonial India have an unusual home—Calcutta HC

Growing interest in India

Dungarpur had a moment of epiphany when he read an interview of filmmaker Martin Scorsese nearly a decade ago that spoke about a festival in Bologna, Italy, which shows restored films. He attended the festival and was completely bowled over. That was in 2014, and he returned to establish FHF.

Its restoration of the 1990 award-winning Manipuri film by Aribam Syam Sarma, Ishanou, was officially selected for a red-carpet world premiere on 19 May 2023 at the prestigious Cannes Classic section of the film festival. It was the only Indian film to be considered under the segment that celebrates restored versions of all-time classics.

There’s a growing audience for restored classics in India, too.

“When Mahal (1949) was screened in Mumbai, so many people turned up. It shows how people are very much interested in watching old films, especially as a theatrical experience,” said Murchana Borah, senior cataloguer at FHF, which restored the film and screened it at Mumbai’s Regal theatre in July this year. In 2022, the foundation also organised a pan-India celebration of Amitabh Bachchan, ‘Bachchan Back to the Beginning’, and in September this year, it organised, Dev Anand @100 to mark the centenary of the Bollywood legend.

The restoration workshops are an extension of this movement to bring back the classics. They are fertile grounds for exchange of ideas among students from different countries. Students realise that films are not immune to climate change or geopolitical changes.

In one of the lectures, David Walsh, training and outreach coordinator at the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), talked about disaster management in film preservation. During the flash floods in Thailand last year, Walsh explained how local residents placed sandbags at the entrance to the country’s film archives storage unit. This simple method worked, he said.

A student raised his hand. What about in times of war, political strife, gunmen and bombs, he wanted to know. What happened to the reels when the Taliban took over Afghanistan, or now, during the Israel-Hamas war?

“Well, there is unfortunately no answer to that question,” said Walsh. “We are hoping to create a central archive, but that is still in talks for now.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)