New Delhi: Retired Lieutenant General Syed Ata Hasnain stood at the podium of the CD Deshmukh Auditorium at the India International Centre earlier this month, explaining that if India were to leave Siachen—the highest battleground of the country—Pakistanis would have a clear run of the world’s second-longest glacier and within 15 km, can link with Chinese presence.

“You will have your two adversaries linked up, occupying the northern boundaries of India,” said Hasnain, his voice booming across the auditorium. “You can have a mutual agreement with Pakistan and pull out, but that can never happen. Because you know what happened in Kargil.”

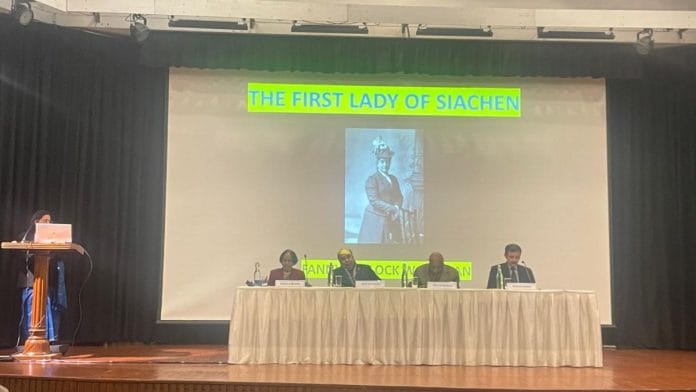

Hasnain was speaking at a talk titled “The first lady of Siachen – Fanny Bullock Workman”. Workman’s climb to the region in 1912 laid the foundation to understanding it. The audience at the event was a mixed bag of IIC members, retired army officers, and enthusiasts from the Delhi mountaineering community. The event was a collaboration between the Himalayan Club and the Himalayan Environment Trust.

Before Retired Brigadier Ashok Abbey revisited Fanny Bullock Workman’s pioneering 1911-12 expedition to the Siachen Glacier, renowned mountaineer Kokila Sudha and Syed Ata Hasnain provided insights into the region, both from their personal experience and the glacier’s strategic importance to the country.

“I couldn’t sleep at night because of the fumes from the kerosene heaters that were inside the fiberglass huts,” said Shyam Saran, President of IIC, who had spent two nights on the Siachen Glacier in 2007, as part of a border infrastructure survey. “Can you imagine, day in and out, those army personnel who were serving there were ingesting these fumes.”

Also read: What happens to sex workers after police raid? New book breaks shelter home myths

Territorial disputes

The Siachen Glacier is an unforgiving region. Saran recalled how helicopters that would deliver supplies would face delays because of the uncertain weather. Snow scooters had to be used to travel to the drop points.

“The morning after we pitched our tent, we had already sunk by one and a half feet,” said Sudha, who was part of the first civilian expedition to Indira Col, a mountain pass at the head of the glacier, in 1997. “We wanted to commemorate 50 years of Indian Independence and hoist the tricolour on 15 August. But we could only do it on 2 September.”

Sudha went into detail about the hardships faced by the group throughout the length of the trek—glacial pools, deep crevices, temperature drops to minus 20 to 30 degrees. “We felt very bad about the soldiers’ lives there,” she said.

When Hasnain took to the podium, a few audience members—mostly retired military personnel—perked up. As he spoke about the military importance of securing the glacier, many nodded their heads in agreement.

“Where did this problem start from? It all started in 1972 when the line of control (LoC) was being demarcated,” said Hasnain, adding that the line was taken to a point called 9842. “NJ 9842 are coordinates on a map. From there, they looked up and saw the glaciers.”

At the time, decision-makers assumed the region beyond was uninhabitable and strategically irrelevant—a land where no vegetation grew and where survival itself seemed impossible. “They used four words in the agreement. It said, the line of control shall go ‘north to the glaciers’,” said Hasnain.

He went on to add that in 1978, India discovered that Pakistanis were sending expeditions into the area. If India had not responded, Pakistan’s presence would have gradually solidified into a territorial claim. Pakistan’s interpretation of the LoC ran from NJ 9842 directly to the Karakoram Pass, effectively placing the entire Siachen Glacier under Pakistani control.

India countered this by extending its claim line from NJ 9842 to Indira Col, asserting sovereignty over the entire Siachen Glacier up to the Karakoram Pass. This overlapping wedge of territory, which was previously unoccupied, became the central dispute.

Also read: When Advani was kept out of the loop on Vajpayee’s nuclear test—‘tears came to his eyes’

Mapping Siachen

Once the auditorium’s lights were switched off, Ashok Abbey used a projector to take the audience back to Fanny Bullock Workman’s expedition. Before diving into her life and tumultuous journey through the glacier, he briefly described its geography. “It is a glacier which is unmatched in its size, beauty and grandeur,” said Abbey. It stretches 76 kilometres in length and is between 3 to 3.5 kilometres wide. “When you look at the glacier from the air, this is what it looks like. A river of ice.” It was Workman who mapped this expanse of white.

Workman, who was born in Worcester, USA, in 1859, came from a wealthy family. She trained as a climber under her husband’s guidance. Her defining achievement came in 1906, when she climbed Pinnacle Peak in the Nun Kun massif of Ladakh, at the time, it was the highest altitude ever reached by a woman.

In 1912, Workman decided to conduct a full reconnaissance of the Siachen Glacier, which she described as the “Great Rose Glacier”. Tragedy struck early when an Italian porter fell into a crevasse and died. Despite this, the expedition continued. “Now, what I am going to show you are her original photographs which she took. This is part of her collection,” said Abbey, using a laser pointer to trace Workman’s expedition. “By the way, this is her original map of 1912, which was published after her exploration of the glacier.”

Abbey closed by stressing on the importance of Workman’s contributions in Siachen. It transformed Siachen from a blank space on maps into a defined geographical entity. Her maps, photographs and place names laid the foundation for later strategic understanding of the region. It was her explorations that first revealed the glacier’s true scale, structure and significance.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)