New Delhi: For decades, South India was hailed as a success story in population control — a region where investments in health, education, and awareness bore fruit. Fertility rates dropped, literacy rose, and the ‘model states’ narrative took hold. But now, as India inches toward redrawing its parliamentary map through delimitation, an unsettling irony emerges: the South may pay a political price for doing everything right.

“The freeze on the expansion and reallocation of Lok Sabha seats has undermined the constitutional provisions and the democratic principle of equality of representation,” said Ravi K Mishra, author of Demography, Representation, Delimitation: The North–South Divide in India. “At present, North and Western India are grossly underrepresented. The East is almost even, while the South remains over-represented.”

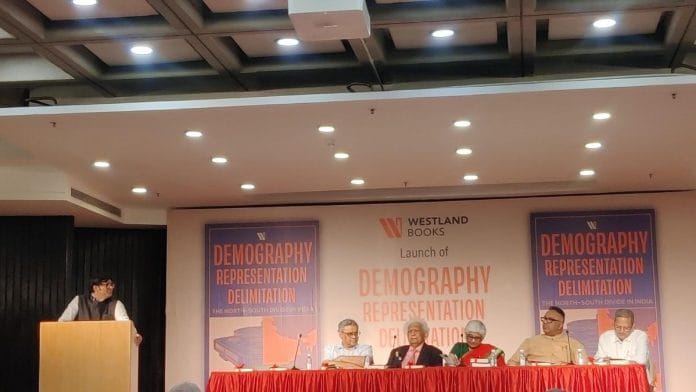

The launch of Mishra’s new book at New Delhi’s India International Centre sparked a timely conversation on a deepening fault line in Indian politics. Hosted by Westland Books, the event featured many prominent voices – Economist and parliamentarian Meghnad Desai, Former MP Swapan Dasgupta, senior journalist and political commentator Neerja Chowdhury, OP Jindal Global University Vice-Chancellor C Raj Kumar, and columnist and former IAS officer Sanjeev Chopra. As India approaches a historic delimitation exercise in 2026, Mishra’s book ignites a crucial debate on the North–South divide. The event unpacked the irony of Southern states facing political penalties for their population control success. With vast disparities in representation looming, speakers urged a reckoning with India’s democratic principles. At stake is not just electoral math, but the future shape of Indian democracy itself.

“India is not just a single nation; It is a multinational state, a collection of many nations. Every linguistic state considers itself a nation. What we are truly creating is a shared civilisation. And in this, it’s vital to respect the dignity of each nation and their right to be part of the Indian Union,” said Meghnad Desai.

A vote in Kerala counts less

Ravi K Mishra began writing his book in the early 2000s, when the landscape was shifting post-liberalisation, and inequalities were increasing—not just in the economic sphere, but also in how states were treated based on their population sizes. The 11th Finance Commission gave significant weight to population in its formula for fund allocation, inadvertently favouring the North, where population growth had surged.

Beyond income and development, a crucial question loomed: How was population influencing access to power?

Southern leaders began raising their voices. If family planning was a national goal, why were the states that succeeded now being sidelined in terms of fund allocation and political representation?

By 2001, the issue had reached a boiling point. Delimitation, which had been frozen since 1976 under the 42nd Amendment, was postponed yet again. As a student of modern history, Mishra turned not to editorials or television panels, but to the archives. He began tracing India’s population journey from its earliest Census in 1872, comparing demographic shifts across four regions: the North (the Hindi belt), South (including present-day Telangana), East (West Bengal, Odisha, and Assam), and West (Maharashtra and Gujarat). What he found upended conventional wisdom. “From 1881 to 1971, the North had the lowest cumulative (population) growth — about 115 per cent,” he said. “The South had grown by 193 per cent, the West by 168 per cent, and the East by 213 per cent.”

By the time family planning became a priority in the late 1960s, South India (including modern-day Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana) had already passed through its most intense population growth period. “Most Southern states were on the verge of exiting the peak phase of their demographic transition,” Mishra said.

These figures feed into today’s charged numbers. Kerala, with over 3.5 crore people, has just 20 Lok Sabha seats. Uttar Pradesh, with a 24-crore population, has 80 — and could gain 40 more after delimitation.. The average southern constituency has 21 lakh people. In the North, it’s over 31 lakh, explained Mishra.

“This delimitation issue has stirred strong emotions in the South. You have MK Stalin, the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, telling people to “make more babies”—something we haven’t heard in decades. And even Chandrababu Naidu, who’s on the other side of the political spectrum, agreed with him on that,” said Neerja Chowdhury, pointing to the growing anxiety in South India.

The concern stems from the likelihood that Northern states such as UP and Bihar, with higher populations, may gain more parliamentary seats, while southern states that successfully curbed population growth could lose representation. Chowdhury praised Mishra’s book for offering a more balanced approach—one that expands the total number of seats in Parliament.

Mishra, in his book, proposes a way to avoid a zero-sum political game. Instead of simply redistributing the existing 543 Lok Sabha seats based on new population data—which would benefit high-growth states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar and hurt states such as Tamil Nadu and Kerala—he suggests increasing the total number of seats. This would account for population changes without penalising states that have successfully implemented family planning, health, and education reforms.

Under a strict redistribution model, South Indian states could lose seats despite their development efforts, creating a sense of injustice and potentially worsening their already fragile equation with the North. Mishra’s alternative is to expand Lok Sabha seats to around 728 or even 791. This way, every state either gains or retains its current representation, avoiding the perception of political loss.

While Kerala may not gain additional seats, it wouldn’t lose any either. As Chowdhury put it, the goal is to create no losers and only winners.

Also read:

‘Don’t shock the system’

Every Census since India’s last major delimitation exercise in 1976 offered a chance to make gradual corrections. But political convenience overruled institutional consistency. Now, with 2026 approaching, that long pause threatens to deliver a political shock.

“You cannot have a 50-year gap and then suddenly decide to shock the system,” said Chopra. “Every 10 years, we had a Census, and we had an opportunity to make minor corrections. We chose not to. Now, when we do it, it will lead to a huge political earthquake.”

In the meantime, trust has frayed. Southern states, having met national family planning goals, now face the prospect of reduced representation.

“There is a Supreme Court Chief Justice who says that when the delimitation happens, states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala are going to lose a large number of constituencies that they have, while states like Bihar and UP, where population is not controlled, will have more constituencies. What will be the state of federalism in India?” said Chopra, highlighting this argument about federalism, which ties back to the demographic reality that the country faces.

Mishra’s book doesn’t offer easy fixes. Instead, it provides what Indian politics has lacked: historical clarity. Drawing on 150 years of Census data, legislative records, and boundary reports, Demography, Representation, Delimitation is a warning flare — a call to rethink what representation should mean in a changing democracy.

At its heart, it’s about power, fairness, and trust — the three pillars on which India must now rebuild the architecture of its democracy. “We were able to handle the language agitation. We were able to handle the linguistic reorganisation of states in 1956. If we follow that kind of thing, I am very sure that our political leadership is mature enough to handle this too,” said Chopra.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)