One of the knottiest and most hotly debated theories of ancient Indian history is that of the Aryan invasion around 2000-1500 BCE. The BJP and RSS have always claimed that India was the cradle of the Aryans — the tribe that introduced the chariot and horse to India and went on to compose the Vedas. Some biological evidence even points to this possibility.

Recent excavations from the nearly 4,000-year-old archaeological site in Sinauli, where a warrior tribe once lived around 1900 BCE, further bolsters this argument, at least according to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

“Western scholars proposed that chariots and weapons came to India with the Aryan invasion, which changed society. The Sinauli excavation denies the entire agenda, as we have evidence of burials of warriors, weapons and chariots which is indigenous in nature,” said ASI’s joint director-general Sanjay Kumar Manjul at the National Museum in Delhi. The event was a lecture titled The Excavation of Sinauli: Revealing the Graves of Great Indian Warriors.

The excavations now form the earliest record of a warrior tribe in the subcontinent. It shows that these people were no ‘migrants’ — but indigenous warriors with a culture distinct from that of the Harappan civilisation, though they existed around the same time as late Harappans. Their practices are echoed in ancient Hindu texts such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Vedas.

Proving Mahabharata is no myth

Excavation of the Ganga-Yamuna doab in Sinauli, which is 70 km from Delhi, had begun in 2005 but was stalled for 13 years.

When the project was resumed in 2018, Manjul unearthed three chariots—and the possibility of re-examining widely accepted history. Now, carbon dating shows that the region was home to one of the earliest warrior tribes in the Indian subcontinent. And archaeologists are still unpacking its secrets.

The chariots, along with the 10 other items Manjul’s team excavated, could be the missing link between ancient Indian history and Vedic culture, according to the ASI.

“The evidence at Sinauli is comparable with literature like the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and Vedas,” said Manjul. “There are references to great warriors like Ram, but there was no scientific proof for it.” For historians and archaeologists like Manjul, Sinauli is important for the cultural understanding of India’s literature.

“Sinauli opens a new chapter in the history of archaeology,” said director-general of National Museum BR Mani in his introduction to the lecture.

Chariots of war

In 2005, archaeologist DV Sharma was leading the project and discovered 116 burials; in 2018, Manjul and his team unearthed coffins, copper shields, and chariots dating back to the second millennium BCE — all pointing to the warrior nature of the Sinauli tribe. They found weapons with hilts and even a copper helmet. Slowly, they pieced together the culture of this tribe of the upper Ganga-Yamuna doab.

That this community was distinct from the Harappan civilisation can be proved due to the presence of ochre-coloured pottery (OCP), copper hoards, and burial sites in Sinauli, according to the ASI.

“The Yamuna belt has a different kind of culture, and 90 per cent of the things in Sinauli are indigenous,” said Manjul. Harappan imprint on Sinauli culture is only about a meagre 10 per cent.

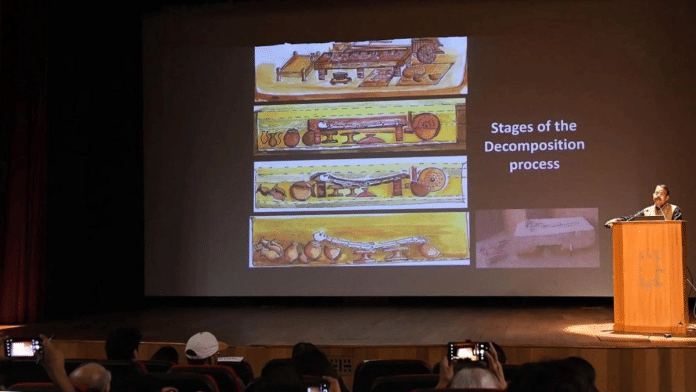

The discovery of the three chariots changed everything for Manjul and his team — it was ‘myth’ getting materialised. The ‘vehicles’ were found buried with the dead warriors. “We only heard about chariots in our literature, but there was no physical evidence [for them],” said Manjul, who, through his 50-minute lecture, circled back many times to link the findings with Vedic literature while dismissing the Aryan invasion theory. He pointed out that the kind of wood used to make these chariots were similar to those described in the Vedas.

These findings not only align with the historical narratives but also resonate with the importance of preserving manuscripts that document our cultural heritage, as they provide insights into the ancient practices and beliefs.

“The findings shocked the archaeological world and brought a new perspective about our history,” said Manjul.

All three chariots are two-wheeled and lightweight with a D-shaped chassis and copper decorations. They were built to be ridden by one person. While more research is needed, Manjul is inclined to believe that the chariot was invented in India.

The findings are in keeping with the RSS’s view. In an episode of the organisation’s Knowledge Series on YouTube titled The Myth of Aryan Invasions, RSS ideologue Krishna Gopal calls the invasion “a hypothesis of the British”.

“Arya means superior. The British questioned how the people of what they saw as a slave country could be superior. Hence, they gave a hypothesis that Aryans had come from outside,” he said.

The 2018 paper by 92 scientists that was published in the peer-reviewed journal Science concluded that the Aryans were Central Asian Steppe pastoralists who migrated to the Indian subcontinent roughly between 2000 BCE and 1500 BCE.

The rites of the dead

According to ASI, the antennae swords and their hilts attached with ornaments also played a ceremonial role. The Rigvedas mention that warriors were buried in full attire with all their weapons. Many of the burials even have peculiar characteristics. “Some are wooden coffin burials, some are with copper sheathing and decorations with steatite inlays,” said Manjul, pointing to pictures on a slide show.

Manjul’s team also found the secret chamber where the priests performed the final rituals before the actual burial. The team postulates that the ritual could have been a day-long exercise.

The Sinauli findings are consistent with ancient Indian literature on another count — the ASI team discovered female remains at Sinauli. “In our literature [Mahabharata and Ramayana], we learned about the female warrior. Possibly the earlier clan [in Sinauli] had female warriors [too],” said Manjul.

A cat’s remains got everyone furrowing their eyebrows. “In previous excavations, archaeologists found burials of dogs. This is the first time a cat burial was found; possibly a domesticated cat,” said Manjul.

While most of the audience was hooked, some sat unconvinced that the Aryans were indigenous.

“They [ASI] just want to prove the Aryans are from this land, not the outsiders,” said Debadatta Ray, a retired engineer who was attending the event.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)