New Delhi: In Ananya Vajpeyi’s latest book, Place: Intimate Encounters with Cities, she turns her gaze beyond streets and skylines. She explores how cities carry love, loss, and the subtle ways they shape who we are.

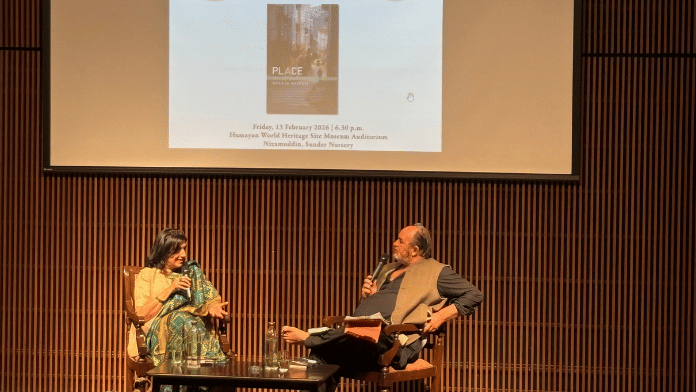

On 13 February, at the Humayun World Heritage Site Museum in partnership with Women Unlimited Ink, Vajpeyi spoke with historian William Dalrymple. Historians, close friends, college students, and members of Delhi’s cultural community were in attendance.

Vajpeyi’s book is a collection of essays exploring cities such as Delhi, Varanasi, Bangalore, Istanbul, Venice, and New York through memory, personal experience, grief, love, and art. Along the way, her parents, teachers, writers, and artists appear in her stories.

From walking the streets of Istanbul through Orhan Pamuk’s novels to carrying her mother’s ashes on the Ganga River in Varanasi, Vajpeyi shows that cities are living companions that hold our grief, joy, and memories.

“A lot of what were my personal likes and dislikes, my personal observations, my own experiences, my memories, once you put them out in a book, they have a life of their own, and they belong to other people who read them, and they agree or disagree or like or dislike them,” said Vajpeyi.

Mirror images

Vajpeyi experienced Istanbul as a city she entered through literature. She immersed herself in the city through the works of Pamuk, tracing the paths the characters in his novels and essays undertook.

“I returned to his books that I had read and loved, and I began walking slowly, sometimes extending for hours and kilometres,” she recalled.

Her daily journeys along the Bosphorus Strait and the streets of Karaköy, Kadıköy, and Beşiktaş became a type of meditation.

In her essay ‘Istanbul Interregnum’, she writes about rediscovering the city through Pamuk’s work.

“Every moment was absorbed in navigating a universe in which I got my bearings from his essays, novels, memoirs and criticism,” she said.

Dalrymple noted that many people experience Istanbul through the eyes of Pamuk and the photographer Ara Güler.

“Those two men have defined Istanbul for so many of us. Those photographs of Güler and the prose of Pamuk,” he said.

Vajpeyi agreed, recalling how Güler was both an obsession and a real presence, and how she saw him wheeled through the streets while living in the same neighbourhood.

Dalrymple then urged Vajpeyi to speak about Venice. He said it beautifully showed how she weaves her own life, family memories, and emotional history into the places she writes about, something he sees as one of the most compelling aspects of the book.

In another essay on Venice, ‘Waiting for Giorgio’, she mixes her personal history with her father’s legacy. Her father had once met Irish playwright Samuel Beckett decades earlier, and she juxtaposed this as a formative moment with her own quest to meet Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben.

“When I sat down to write, I started the essay by describing what that meeting with Samuel Beckett meant for my father… 40 years before I met Agamben in Venice,” she said.

She moved through Venice with the same alertness she had carried in Istanbul — pausing before Renaissance artist Giovanni Bellini’s paintings at the Fondazione Querini Stampalia, then hurrying through narrow lanes in search of Agamben. And in the middle of all this, she noticed the art, philosophy, history, alleys and lights, all of it folded into the geography of the city.

Also Read: I cried during my research years because I struggled with my Sanskrit texts: Ananya Vajpeyi

The Indo-Persian cultural world

The conversation then shifted to Delhi and the Indo-Persian cultural world. Vajpeyi read from an essay that begins with a memory of listening to Pakistani singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan in the city in the 1990s.

“Now we are singing a poetry in the Persian,” she recalled him saying. She turned that phrase over for years. “Poetry in Persian. A poem in Persian. But it never sounds quite right, except in Nusrat’s idiosyncratic grammar.”

Vajpeyi argued that one does not say “a poetry” or “the Persian.” It would normally be “singing poetry in Persian” or “singing a poem in Persian.” Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was likely translating directly from Urdu or Punjabi into English, which gave the line its unusual grammar, she theorised, and while it sounds incorrect by formal rules, it felt powerful and memorable in his voice. Vajpeyi struggled to connect with the sentence in her mind because the grammatically correct versions lose the charm and personality of Nusrat’s original phrasing.

The essay then turns to the monsoon-soaked Delhi, where she writes, “Paradise is really a garden in the rain. Paradise is the crowding of the summer sky, with clouds so dark they are almost black.”

From there, she turns to the 13th-century Sufi poet Amir Khusro and roots his creative life in the same landscape. She writes that he found his music in Delhi, a place where “poet and river in flood, a lovemaking of language.”

In another essay, ‘Kashi Karvat’, Vajpeyi returns to the city carrying her mother’s ashes, remembering her parents’ dreams of an idyllic old age there. She recalled how in February, she and her cousins took a boat on the Ganga River. This made her recall her own childhood on the river, her father diving in, her mother clinging to his arm, laughing.

Vajpeyi recalled how years later, after her father’s death, her mother stepped into the water again. “I knew their love would hold them aloft,” she read from the book.

In Varanasi, the Ganga River briefly flows north before turning east again. “This is called Kashi karvat, the turning point at Kashi (old name for Varanasi). When this comes, one turns from the future towards the past, like a sleeping person in the middle of the night.”

However, she made it clear that her aim was never to produce an ethnography or a sociological analysis, nor to confine any city to a single, fixed story. She said, “It’s one person’s perception at one meeting.”

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)