New Delhi: Amrita Sher-Gil was not just an artist who painted India, but an artist who returned to find India and reimagined how the country could see itself. More than a century after her birth, Sher-Gil’s work continues to feel timeless, intimate, and unsettlingly alive.

“Amrita Sher-Gil changed the face of modern art and paved the a way for it in India,” said art historian and writer Yashodara Dalmia.

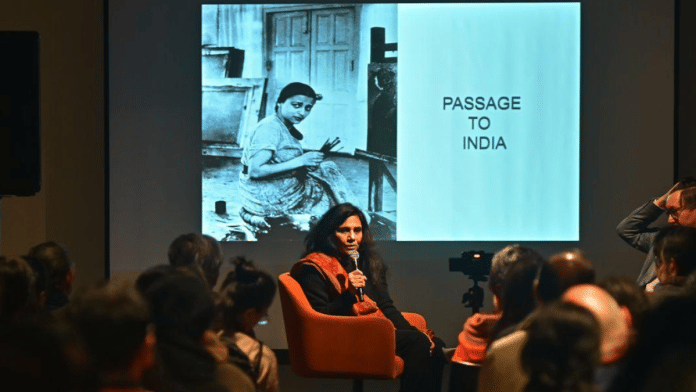

Sher-Gil’s work has refused to be archived into history, and it is precisely what the lecture ‘Amrita Sher-Gil: The Passionate Journey’ by Dalmia at DAG on 27 January was all about. Art enthusiasts, artists, and students shared this evening, remembering Sher-Gil’s life and her impact on Indian modern art.

Born in Budapest on 30 January 1913 to a Sikh father and a Hungarian mother, Sher-Gil lived a life compressed by time and intensity. She died when she was only 28 years old, yet left a body of work that altered Indian modernism forever. Charismatic, fierce, intelligent, and beautiful, Sher-Gil soon became a name to be remembered.

Dalmia traced Sher-Gil’s journey from Europe to India, from academic realism to a deeply personal modernism, from observing bodies to understanding lives. At its core, Dalmia concluded, Sher-Gil’s story is about returning, about women’s inner worlds, and a melancholy of ordinary everyday existence.

“The journey of one of the most significant artists in India can be traced from her training in Paris to its triumphant culmination in India,” said Dalmia.

Also Read: Artist Gogi Saroj Pal painted women adoring themselves. That was her rebellion

The Paris effect

When Sher-Gil arrived in Paris in 1929, she was only 16 years old, but already knew her calling. She trained herself first at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and later at the École des Beaux-Arts, where she studied the rigour of European academic realism – studio portraits, nudes, anatomy studies, and landscapes.

Her breakthrough came early when Two Girls (1932) won her a gold medal at the Grand Salon in 1933, making her an associate, a rare honour for a young Asian student.

During this period, she produced hundreds of studies, scrutinising posture and anatomy. Dalmia noted that even then, her work carried a distinct signature.

“In testing the veracity of the form, she seemed to imbibe its essential value; thus, making her work distinctive even at this early stage,” she said.

But Paris also shaped her personally. She lived intensely, loved deeply, and formed close relationships, including one with fellow student and artist Boris Tarslitsky, who once told Dalmia in the early 2000s that Sher-Gil’s presence had never left him. The influence of French artist Paul Gauguin loomed large on her, especially in her search for darker palettes and non-Western forms. Her self-portraits from this time echo a yearning to step outside Europe’s gaze and inhabit another visual world.

Yet Paris, for all the freedom it offered, also left her wanting for something more. She sensed that modernism alone could not be sufficient.

“Our long stay in Paris has aided me to discover, as it were, India. Modern art has led me to the comprehension and appreciation of Indian painting and sculpture. It seems paradoxical, but I know for certain that had we not come away to Europe, I should perhaps never have realised that a fresco from Ajanta or a small piece of sculpture in the Musée Guimet is worth more than the whole of the Renaissance. In short, now I wish to go back to appreciate India and its worth,” she wrote in a letter to her mother from Budapest in 1934, that Dalmia mentioned in her lecture.

This realisation was a turning point in Sher-Gil’s personal and professional journey.

Also Read: India privatised Amrita Sher-Gil’s story, ignoring Hungarian roots. Delhi exhibition reclaims it

The journey home

Sher-Gil returned to India in December 1934, and almost immediately, her art began to change. She adopted the saree and immersed herself in the visual languages of Pahadi, Rajpur, and Mughal miniatures, as well as the murals of Ajanta and Ellora.

And what emerged from that was reinvention.

Paintings such as Three Girls (1935), Hill Women (1935) and Hill Men (1935) revealed a new sensibility: figures grouped yet profoundly alone, their dignity heightened by restraint.

Dalmia described this period as Sher-Gil’s awakening to a different India. “It was not the voluptuous, colourful, sunny India of travel posters, but an India desolate yet strangely beautiful, over which an indefinable melancholy reigns,” she said.

Her travels to South India became a turning point, Dalmia explains. Sher-Gil was deeply moved by the cave paintings and sculptures of Ajanta and Ellora. The rhythms of the Ajanta figures, which seemed to rise out of the rock, and their subtle yet luminous colours carried her on an intensely visual journey.

The sights and sounds around her added to the experience. Writing about this experience, Sher-Gil, according to Dalmia, had once said, “I don’t know how I will ever resign myself to living and painting in Simla, or for that matter anywhere in North India, after seeing the South.”

The sculpted rhythms of Ajanta were later absorbed into The Bride’s Toilet, painted after her return to Simla in 1937. The theme draws from courtly miniature traditions, where a woman adorning herself is often watched by a hidden lover. In Sher-Gil’s version, however, the fair-skinned, upper-caste bride turns towards the viewer, her face marked by quiet desolation. Her hennaed hands, symbols of fertility, only heighten the sense of inner distress.

“Intuitively aware of the deeply sensuous rhythms of women’s lives, she also empathised with the frustrations of their truncated selves,” said Dalmia.