Climate change is no longer solely an environmental concern, it also disrupts health systems, economic resilience and demographic stability on a global scale.

Global temperatures are projected to rise by more than 2.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) “middle of the road” trajectory. This path is already materializing through increasingly frequent and intense climate-related events, including wildfires, heat waves, prolonged droughts and widespread degradation of air quality around the world.

While climate change is often regarded as the primary environmental consequence of industrialization, air pollution – especially from energy, transport and urban development – is an equally pervasive and systemic threat.

Air pollution includes fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ground-level ozone – a secondary pollutant created when sunlight reacts with primary pollutants such as emissions from vehicles and industry. It’s both a chronic stressor on human health and an accelerant of climate vulnerability. Its impacts are especially pronounced among older adults, who face greater health risks due to age-related changes and higher rates of pre-existing conditions.

In many rapidly urbanizing and industrialized regions of the world, the convergence of dense urban populations, rising pollution levels and ageing demographics is amplifying health risks and socioeconomic inequalities. The resulting compounding effect has not yet been fully addressed in existing climate, labour or health policies.

How air pollution affects India

India is home to 140 of the world’s 200 most polluted cities, and with nearly 12% of its population aged 60 and above (a figure that’s expected to reach 19% by 2050), the country stands at the intersection of a pollution crisis and a demographic transition. This has profound implications for health systems, workforce productivity and economic sustainability, particularly as India’s growing economy increasingly depends on older workers.

Air pollution increases the demand for chronic care services, disproportionately straining public healthcare systems in the country’s poorer states. Higher morbidity in the 50+ population can lead to earlier pension claims and rising public expenditure on elderly care. The growing need for non-communicable disease management in aged populations already exceeds current capacity.

A 2019 Lancet study estimates that 1.7 million premature deaths in India were linked to air pollution that year, with a significant share comprising adults aged over 50. Ongoing exposure to air pollution increases the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, ischemic heart disease and stroke – all of which already disproportionately affect older adults. Pollution-related inflammation also exacerbates cognitive disorders, including early-onset dementia.

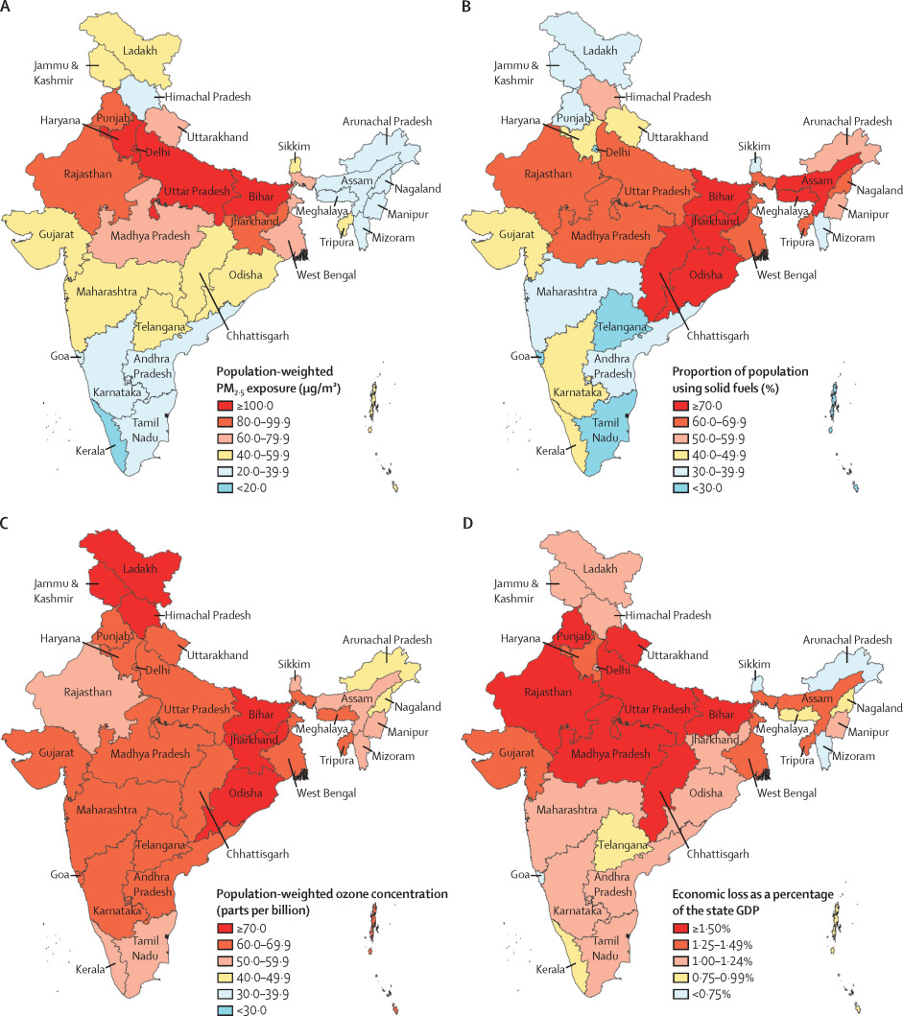

Economic loss due to premature deaths and morbidity attributable to air pollution in the states of India, 2019 Image: Health and economic impact of air pollution in the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, The Lancet.

These health impacts translate directly into economic consequences. Older workers, especially those in informal and outdoor occupations such as agriculture, construction and street vending, face reduced physical stamina, higher absenteeism and early exits from the labour market due to pollution-linked illness.

Pollution exposure can also reduce effective working hours by up to 15% in heavily polluted regions. This reduction affects household income and intergenerational support systems, decreasing the ratio of productive workers to dependents and potentially increasing reliance on state support while weakening informal safety nets. This could ultimately reduce national productivity.

Tackling air pollution

Addressing such issues will require integrated strategies that align environmental risks with labour, health and social protection policies.

After the second World Health Organization (WHO) Global Conference on Air Pollution and Health in March 2025, countries pledged new funding to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and strengthened air quality standards in line with WHO guidelines. And at the 78th World Health Assembly the following May, governments endorsed WHO’s updated roadmap, which targets a 50% reduction in premature deaths from anthropogenic air pollution by 2040.

This global commitment sets the foundation for more coherent national responses in three areas:

1. Labour policy

Older adults in high-exposure occupations – transport, street vending, construction – face heightened risk from pollutants like PM2.5 and ozone. So, governments should set exposure-adjusted guidelines and adopt flexible work scheduling tied to real-time air quality indices. Installing purification systems in offices and small enterprises employing older adults could lower chronic exposure. These actions should align with the WHO resolution and its supporting tools, such as AirQ+ and Climate Change Mitigation, Air Quality and Health (CLIMAQ-H), which quantify the health and economic benefits of air quality improvements.

2. Public healthcare systems

A shift to a preventive, age-responsive model for healthcare is crucial. Routine respiratory and cardiovascular screenings should target adults aged over 50 in high-risk areas. Primary care networks such as India’s Ayushman Bharat Centres could be used as delivery channels. Partnerships with private sector actors such as manufacturers, distributors and retailers could help expand access to high-quality protective equipment, including N95 masks and household air filtration systems, especially in pollution-prone regions. This would help to reduce individual exposure to harmful airborne pollutants like PM2.5 and ozone, particularly among older adults and people with chronic health conditions.

3. Social protection systems

Reforms in this area should reflect the long-term risks of pollution exposure. This includes introducing health insurance riders for pollution-linked chronic conditions, with targeted subsidies at municipal or state levels. Pension schemes in high-risk places could integrate air quality-linked top-ups or incentives for older adults who postpone retirement or shift to safer work. These adaptations would address environmental issues while promoting equitable and fiscally sound aging policies.

Protecting the longevity economy

In a longevity economy, people live long, healthy and financially resilient lives thanks to robust pensions, retirement systems, social benefits and healthcare. But the world’s ageing populations are no longer simply a demographic concern, they are becoming vulnerability multipliers in the face of accelerating climate change and air pollution.

Chronic exposure to polluted air undermines the health and functional capacity of older adults, affecting wider economic productivity, healthcare system sustainability and social equity. These consequences are particularly acute in rapidly urbanizing regions and low-resource settings, but they are increasingly relevant for countries at all income levels.

Protecting the longevity economy will require a shift to preventive, risk-based planning that sustains wellbeing, productivity and equity – particularly in ageing, climate-affected countries such as India.

This article is republished from The World Economic Forum under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.