New Delhi: On the night of 31 March, 1997, angry students from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) gathered at the Bihar Bhawan in Delhi demanding that Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav come out and meet them. According to a Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist)-Liberation leader, Lalu responded by calling the students “drug-crazed upper caste feudal boys.”

The JNU students were protesting against the murder of Chandrashekhar Prasad, a rising star of the CPI(ML) Liberation, and a two-time JNUSU president, who was shot dead in Siwan by sharpshooters allegedly in the employ of the notorious Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) strongman and MP Mohammad Shahabuddin.

Over 28 years later, the RJD has fielded Shahabuddin’s son Osama Shahab from Raghunathpur in Siwan as its candidate for the Bihar polls, in which it is in alliance with the slain communist leader’s party, the CPI(ML) Liberation.

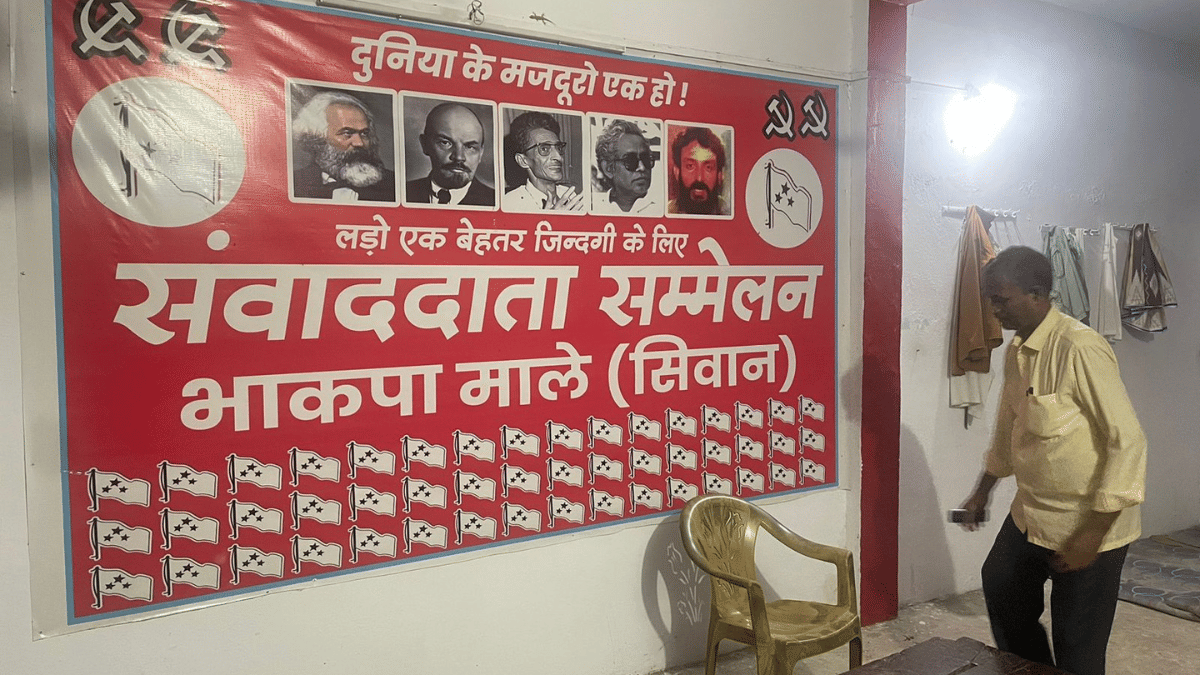

In Siwan, a district once synonymous with Shahabuddin’s iron-fist rule, goes to polls on 6 November, CPI(ML) Liberation district secretary Hans Ram Nath sits in his party office in front of a large poster bearing the faces of Marx, Lenin, Charu Mazumdar, Vinod Mishra, the former general secretary of the party, and Chandrashekhar.

Nath has just finished campaigning for the day in a dust-caked Wagon R car before arriving at the decrepit two-storey party office. It is in the mosquito-filled hall of this office that Nath along with other party workers have been camping the last few days.

That his party is in alliance with the RJD, to which Shahabuddin belonged and from which his son is now contesting, does not seem to evoke any sense of irony in Nath.

“Those were different times. That was a time when the RJD belonged to the ‘shasak varg’ (the ruling class), so we opposed them, and the atrocities that were unleashed on the marginalised,” he says. “These are different times. The country is being injected with communal poison by the BJP and the RSS, so we have to fight them first.”

CPI(ML) Liberation general secretary Dipankar Bhattacharya is even more unequivocal. “I don’t think it (Osama’s nomination) should be bracketed with Shahabuddin… Shahabuddin, obviously, had his own criminal record and we fought against him after Chandrashekhar’s assassination. And he went to jail. He’s no more. Chandrashekhar and all the victims of terror in Bihar, I think, got their justice,” he tells ThePrint.

Bhattacharya and his party’s stand is a complete volte-face from over a decade ago when the CPI(ML) Liberation did not have the compulsions of coalition politics—since 2020, it has been a part of the Mahagathbandhan. In 2012, when a Patna court convicted three men for Chandrashekhar’s murder, the CPI(ML) Liberation dismissed them as mere “hitmen”, and stated most unequivocally that “the real killer” was Shahabuddin.

“Until and unless Shahabuddin, the main political conspirator behind the assassination, is punished in the most severe way, there can be no justice for Chandrashekhar,” the party had declared. While Shahabuddin’s alleged role was investigated in the case, he was never charge sheeted in the case.

Party workers in Siwan cloak themselves in anonymity to conceal their unease. In hushed whispers, they admit that the situation is far from ideal.

“We ourselves have sat on endless ‘dharnas’ (protest) against Shahabuddin. Across the board, we were the only ones to ever speak against his reign of terror,” an old CPI(ML) Liberation worker in his 60s says. “Now, we look the other way when we have to stand in alliance with his son. But what does one even do? In politics today, the corollary of being too principled is to risk perishing.”

The CPI(ML) Liberation’s journey—from being the fiercest critic of the RJD government for soft-pedalling in the case of Chandrashekhar’s murder, and demanding that Shahabuddin be punished “in the most severe way,” to now being in alliance and allotting a ticket to his son—reflects the long arc of Left politics in Bihar, marked by a shift from revolutionary idealism to political pragmatism.

To be sure, the shift is bitterly resented by the now largely defunct ultra-Left factions, for whom the Communist parties have become ‘peechlaggu’ (tag along) to the RJD—abandoning the higher pursuit of revolution for paltry electoral gains.

Yet, it is perhaps this new-found pragmatism that makes the Left endure in the state at a time when it faces near-complete wipeout from the electoral map of the rest of the country, barring Kerala. When the Communist Party of India, the CPI (Marxist) and the CPI (ML) Liberation won 16 of the 29 assembly seats they contested in 2020, it was this quiet resilience of Left politics in Bihar that was on display.

While the CPI and the CPI(M) each won two seats out of the six and four they contested, respectively, the CPI(ML) Liberation’s win in 12 of the 19 seats was stunning —it had a strike rate of 63 percent, second only to the BJP’s 67 percent. Compare this to the past three elections when the CPI(ML) Liberation won 3, 0 and 6 seats in 2015, 2010 and 2005, respectively.

While political analysts and journalists marvelled at the result, piecing together various explanations for the Left’s “revival,” tracing Bihar’s political landscape across space and time reveals that the Left’s revolutionary politics—and its sustained, if limited, electoral presence—have been shaped by a long and layered history.

The early seeds of ‘revolution’

“In many ways, Bihar’s economic and social fate was sealed by the Permanent Settlement introduced by the British in 1793,” says Mujtaba Hussain, a former professor of sociology at Patna University. “Bihar never had princely states, so power was always exercised arbitrarily, and often brutally by the landowners, all of whom whimsically ran their estates like their own private kingdoms.”

What this meant was there was no overarching rule of law in this region, and with the coming in of the Permanent Settlement, zamindars had absolute power over those who worked for them.

Given that the zamindars, who had to pay a fixed amount to the British, had no real incentive in actually increasing agricultural production, there was no investment in agriculture whatsoever, says a former activist of the Democratic Students’ Union, a far-Left student organisation with Marxist–Leninist leanings, inspired by the ideology of the CPI (Maoist), who belongs to Arwal.

“As a result, the surplus would go to the zamindars and not for agricultural production. Moreover, the farmers had to not only run the state, but also provide for its mediators—the zamindars.”

Old safety nets that once shielded cultivators and peasants began to fall away. Bihar’s countryside took on a distinct caste-cum-class character, where economic deprivation became inseparable from social oppression and cultural humiliation.

In the 1930s and 1940s, when large parts of India were consumed by the freedom movement, pockets of Bihar were already seething with a different kind of revolutionary zeal. This was in large part due to the arrival of a Jujhautia Brahman sanyasi, Swami Sahajanand Saraswati—“the foremost kisan leader in India”—on the scene in the late 1920s.

A religious reformer, Congress nationalist, kisan leader, and militant agitator, Sahajanand was all these things at once. In 1927, he started the Kisan Sabha in West Patna district. In the early years, Sahajanand’s peasant movement and the Congress had no apparent tension. In fact, upper-caste Congress leaders offered enthusiastic support to the Sabha thinking it would bring peasants in large numbers into the Civil Disobedience Movement.

However, problems began to creep in slowly as the Sabha continued to raise issues of the peasantry pressing for the reduction of rent, while the Congress sought to brush agrarian conflicts under the carpet in the name of national unity. By the mid-1930s, Sahajanand was already thinking of class struggle as the only method to liberate the oppressed masses from the many-folded slavery and subjugation, writes Francine R. Frankel in the book, ‘Dominance and State Power in Modern India’.

In meeting after meeting, Sahajanand referred to zamindars as a “parasitic class,” “a useless burden on the world”, and called upon the peasantry to overcome their caste divisions, arguing that “only capitalists, zamindars and peasants are castes, not others”.

Even though Sahajanand did not belong to the Left officially, his politics was seeped in communist fervour. By the mid-1930s, the Kisan Sabha already began to organise tenants to forcibly regain their lands from which they were evicted. In a phenomenon that would be repeated in the 1980s and 1990s in the form of large scale massacres of Dalits by the private militias of the upper-castes, the zamindars began to mobilise their ‘Lathaits’ (musclemen), who formed the coercive arm of their feudal power, to beat up the revolting kisans.

For its part, the Congress began to denounce the activities of the Sabha with growing vehemence. “Those who preach class hatred, are enemies of the country,” senior leader Vallabhai Patel remarked. From here on, the peasant movement and the Congress never saw eye to eye.

Also Read: From pre-Emergency to post-Lalu era, the story of Congress’s irreversible decline in Bihar

Blind to caste

After Independence, two things became clear. One, the revolutionary forces unleashed by the Kisan movement were there to stay. It was no coincidence, after all, that Bihar became the first state in post-Independence India to abolish zamindari in 1950.

Two, the upper castes would not take the perceived onslaught on their traditional privileges lying down. The ‘Lathait model’ they had harnessed for decades would now be fine-tuned to strike back at the forces of modernity with a vengeance.

It was no coincidence either, therefore, that days before the zamindari abolition bill was to be tabled, Bihar finance minister K.B.Sahay was run down by a truck, allegedly on the orders of the Darbhanga maharajadhiraj. The sight of a bandaged Sahay presenting the bill on the floor of the assembly was to be a lasting evidence of exactly how difficult it would be to break the zamindars’ stranglehold over Bihar.

Despite the earliest land reforms in India, the feudal nature of agrarian Bihar survived as large landowners managed to save substantial portions of land. As argued by journalist Sankarshan Thakur in his book, ‘The Brothers Bihari’, Bihar might have been the only state in the country, where one not only had zamindars, but also ‘paanidars’—upper-caste families that enjoyed territorial privileges over parts of rivers.

“It was impossible to do anything for us,” says Nath, who belongs to a Dalit family in Siwan. “Our grandparents and parents were not allowed to sit on a khat, nobody was allowed to vote—I remember watching members of my caste being dragged out of a polling booth—and everyone thought this is how it will always be.”

“Like all other villages, we had a strongman, Ramayan Singh, a Bhumihar, who owned petrol pumps, buses, trucks. He ruled the village like his fiefdom.”

At this time, however, when struck by the fear of their privileges being dismantled, the upper-castes were tightening their exploitative grip over the lower castes, the Communist politics was dithering from within.

“Their (the communists’) entire leadership came from the upper castes, and the fundamental contradiction was that they wanted to see the conflict in agrarian society as one between the peasant and the landlord alone, and not between the upper castes and the lower castes,” says Hussain.

“In rural Bihar, there is a proverb that runs like this ‘Kaeth kichhu lenen delen, Barahman khiyaulen, Dhan pan piyaulen, au rarjati latiaulen (A Kayastha does what you want on payment, a Brahman on being fed, paddy, betel and on being watered, but a low-caste person on being kicked,” he adds.

“It basically shows that there were deeply discriminatory perceptions and practices with regard to upper and lower caste peasants…As a Bhumihar cultivator, even if one was very poor, one would not face the humiliation faced by a Dalit worker…The upper-caste communist leaders refused to see that. They wanted to challenge the economic structure without challenging the culture that breathed life into that structure.”

It is for this reason that many observers believe the socialists, who channelised the growing aspirations of the backward castes—the elite among whom benefitted the most from both universal adult franchise and the land redistribution through the abolition of zamindari—rose to dominance, while the communists lagged behind.

As argued by Frankel, “No political party, including the two communist parties, made any effort to organise agricultural labourers, although by 1971 they constituted the largest percentage of workers in a majority of Gangetic Bihar. Moreover, except in pockets, their economic condition showed no improvement, while the Harijans among them continued to be subjected to brutal social abuse.”

By the 1960s, it was amply clear that peaceful approaches to ameliorating the condition of the landless workers had failed.

A violent movement that erupted in 1967, some 500 km in neighbouring Bengal, would finally change the fate of landless workers in Bihar.

‘The flaming Fields of Bihar’

The late 60s and early 70s was an age electrified by Mao, Che, and May ’68—a global insurgency of the young and the dispossessed demanding revolution, not reform. Across continents, the revolutionary Left believed history itself was cracking open—that capitalism, colonialism, and complacency could all be swept away by struggle. India was no exception.

“I was a student in Patna when I first heard of Naxalbari,” recalls Arvind Sinha, a member of one of the ultra-Left factions of the CPI(ML). “The slogan then was ‘Sarkar nahi, system badalna hoga’—not just the government, the system must change. That struck a chord with me. We had seen such upheaval in the 60s — the Congress government had fallen, a new one with social justice apparently on its agenda had come and gone, and yet nothing changed on the ground.”

Dressed in a blue cotton kurta, Sinha sits in his living room strewn with bundles of newspapers and books — among them Joseph Schumpeter’s ‘Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy’ and a Hindi volume on Che Guevara. The old TV set, the walls lined with curling calendars, and a tiny picture of Marx hanging on the wall give the room the air of a space long frozen in its revolutionary past.

“So, I followed the call for revolution through direct class struggle and got involved in directly mobilising agricultural workers…We went from village to village in the Bhojpur region telling agricultural workers to not just passively resist against feudal landlords, but also resist violently if needed. We would train them, and ask them to not accept any form of oppression—economic or social,” he says.

In 1969, the CPI(ML) was formed under the leadership of Charu Mazumdar. It was a party formed as a result of the CPI and CPI(M)’s “betrayal” of the revolution by participating in elections. It advocated a protracted people’s war—a revolution led by peasants as a means of overhauling the Indian state.

Naxalism spread in Central Bihar like fire. As noted by Aniket Nandan and R. Santhosh in the paper, ‘Exploring the changing forms of caste-violence: A study of Bhumihars in Bihar, India’: “Rather than any ideological affiliation to Naxalism, individuals from lower castes firmly believed that the Naxalites are there to stand with them in their fight for justice; many lower-caste people eventually became Naxalite sympathisers.” By the mid-1970s, the whole of Central Bihar came to be known as the “Flaming Fields of Bihar,” a term coined by the CPI(ML) Liberation.

The results were there for people to see. As argued by Rajesh Kumar Nayak, in a paper titled, ‘Naxalism, Private Caste Based Militias and Rural Violence in Central Bihar’, “under the Naxalite influenced area, one occasionally could come across with a red flag, determinedly planted in the middle of the field.”

It meant the land was contested and claimed by Naxalites—which often resulted in violent confrontations. If the Naxalites won, the land would be distributed to the poor. According to Nayak, there were reports that by the early 1990s, the Naxalites had seized 1,000 acres of land in Patna, 616 acres in Palamu, 4,500 acres in Gaya, and 1,000 acres in Nawada and distributed it to the poor.

Recounting the observations of a journalist at the time, Nayak writes that by the 1990s, there was “a new found confidence among the Dalits.” “Unlike the past, the Dalits did not fold their hands. They did not bend their body. They did not call anybody ‘Huzur Sahib Sir’ or anything like this.”

The response of the landlords was prompt, vicious and bloody.

Starting from the late 1960s itself, the ‘Lathait model’ was resurrected to create Senas, or the private militias along caste lines. The Kuer Sena (1969), the Kuwar Sena (1979), the Sunlight Sena (1988), and the Samajwadi Krantikari Sena were formed by the Rajputs. The Brahmarshi Sena and the Diamond Sena were formed by the Bhumihars.

Even the backwards, who in many places, came to exhibit the feudal ethos of the upper-castes, organised themselves in Senas. The Kurmis formed the Bhoomi Sena. The Yadav landlords of Jehanabad formed the Lorik Sena. At the peak of the anti-Mandal agitation, the Yadavs even came together with Bhumihars and Rajputs, who themselves had been traditionally caught in internecine conflicts, to form the Kisan Sangh.

The slogan of the Diamond Sena captured the menacing urgency with which landlords sought to preserve their turf: Mera Itihas Mazdooro Ki Chita Par Likha Jayega (in History, my name will be written on the funeral pyres of labourers).

In 1994, bringing together several private militias, Brahmeshwar Singh, a Bhumihar, formed the Ranvir Sena—more dreaded and lethal than any of its predecessors. In its first year, it murdered CPI(ML) Liberation leaders. But starting 1996, it unleashed a cycle of massacres—a dance of blood and retribution that would scar Central Bihar’s countryside for years.

Bathani Tola (1996), Laxmanpur Bathe (1997), Sankarbigha (1999), Miyapur (2000), Senari (1999), Ekwari (1997), Narayanpur (1999)—massacres in which dozens of agricultural workers were killed at once occurred with startling frequency. Children and women were deliberately targeted—a “strategy” admitted to by the Sena’s chief.

The Ranvir Sena, Singh once said in an old interview from the jail, kills women and children, “who otherwise become Naxalites when they grow up or would give birth to future Naxalities.”

The Lal Sena of the Communists—largely comprising the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC), the Party Unity, the Peoples War Group—whose ranks consisted largely of Dalits, were no less brutal in their response. The MCC, for instance, hacked nearly 40 Bhumihars to death in 1992.

“The Communists who began to gain power from these wars themselves began to get corrupted by their power,” Sinha says. “They began to hold jan adalats (people’s courts), control areas where they would win, and often have violent confrontations with other factions within the Communist ranks for control.”

“By the end of the 1990s, people were fed up with the violence. I also started feeling if there would be an end to this bloodbath,” he says. “It is true that the government responded to the violence perpetrated by Naxalites with much greater force, and let the violence by the upper-caste militias slide, but the ordinary villagers began to feel that their economy has been totally devastated.”

“Calls of compromise came from the villagers on both sides,” he says. “That wisdom came from the people.”

Also Read: Lalu vs the ‘Seshan Code of Conduct’: EC was key player, not umpire, in Bihar polls 30 years ago too

The electoral way

There is a difference between targeted attacks on a few landlords and caste-based massacres, explains Sinha. “That violence of mindless massacres died its own death…But what we have seen with CPI(ML) Liberation is also a betrayal of the actual ethos of communism.”

“They have stopped talking of revolutionary politics, and made elections their central plank… With such politics, all you can hope is to piggyback and get some seats here and there.”

For the CPI(ML) Liberation, however, electoral politics is not an escape, but a realisation that one cannot boycott what they don’t have. “Under Charu Mazumdar, we had thought that we should boycott elections. But as our leaders kept working on the ground, they realised that landless cannot boycott what they don’t have—the landlords stopped us from voting for years, so our party decided to win this fundamental right to vote,” says Nath.

Yet, it is from the legacy of Charu Mazumdar and the bloody struggle of the 1990s that the CPI(ML) Liberation continues to gain. Even in the last election, the party along with CPI and CPI(M) had done well in the western districts of Siwan, Bhojpur, Buxar, Rohtas, Jehanabad and even Patna, collectively known as the Bhojpur region—a fortress of class struggle since the times of Majumdar. So, it is not “out of nowhere” that the Left performed in these regions.

Moreover, unlike in previous elections, in 2020, the CPI(ML) Liberation formed an alliance with the RJD, Congress, etc. allowing them to win significantly more seats than they previously did. The alliance prompted several observers to argue that the CPI(ML) Liberation’s performance does not indicate any real resurgence, but was merely a case of political piggybacking.

However, this is not a sufficient explanation for their performance in 2020, contends Hussain. “You have to have a base of your own that gets invigorated through an alliance, but that base must exist in the first place.”

“In Bihar, the CPI(ML) Liberation’s biggest strength has been its mediation with caste. You travel across, and realise that not only their followers, but leaders are from lower castes,” the retired professor says.

But according to most observers and voters, the fact that the CPI(ML) Liberation never abandons its agitational politics on the ground whether or not they gain electorally or not is undisputed.

In Siwan’s Chakra village, Shanti Devi relates an incident that happened two years ago.

“Some private company came here and went door to door offering a loan. I was in need of money, so I agreed. I was supposed to pay them an interest every month. But once, my son fell sick, and I could not pay,” says the Dalit woman in her 40s. “They started harassing me for money every day—hurling abuses, threatening me and my family…It was only when Malay (a CPI(ML) Liberation leader) came to my rescue did they back off.”

They do this even when they don’t win, she adds.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Karpoori Thakur: The convenient resurrection of Bihar’s Jannayak