Any financing that’s secured by collateral — steel mills, textile factories, power plants, roads or land — is in trouble in India. A multiyear investment slowdown has decimated credit quality. Now, the problem is spreading. The near-recession in the consumer economy means unsecured lending could be the next domino to fall.

With business collateral losing its sheen, India’s top three private-sector banks have been expanding their credit card and personal loan business at 30%-plus rates, double the pace of growth in their corporate loan book. They can’t keep up for long. If they try, they would only be storing trouble for the future.

Why? For one thing, the quality of the next borrower is suspect. About 20% of all active credit-card customers in India are in the highest category of creditworthiness, according to TransUnion Cibil, which assigns scores. But among those who signed up last year, only 3% belonged to this least risky group, an analysis by Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. shows. The next person to apply for and get a credit card in India is more likely to be subprime.

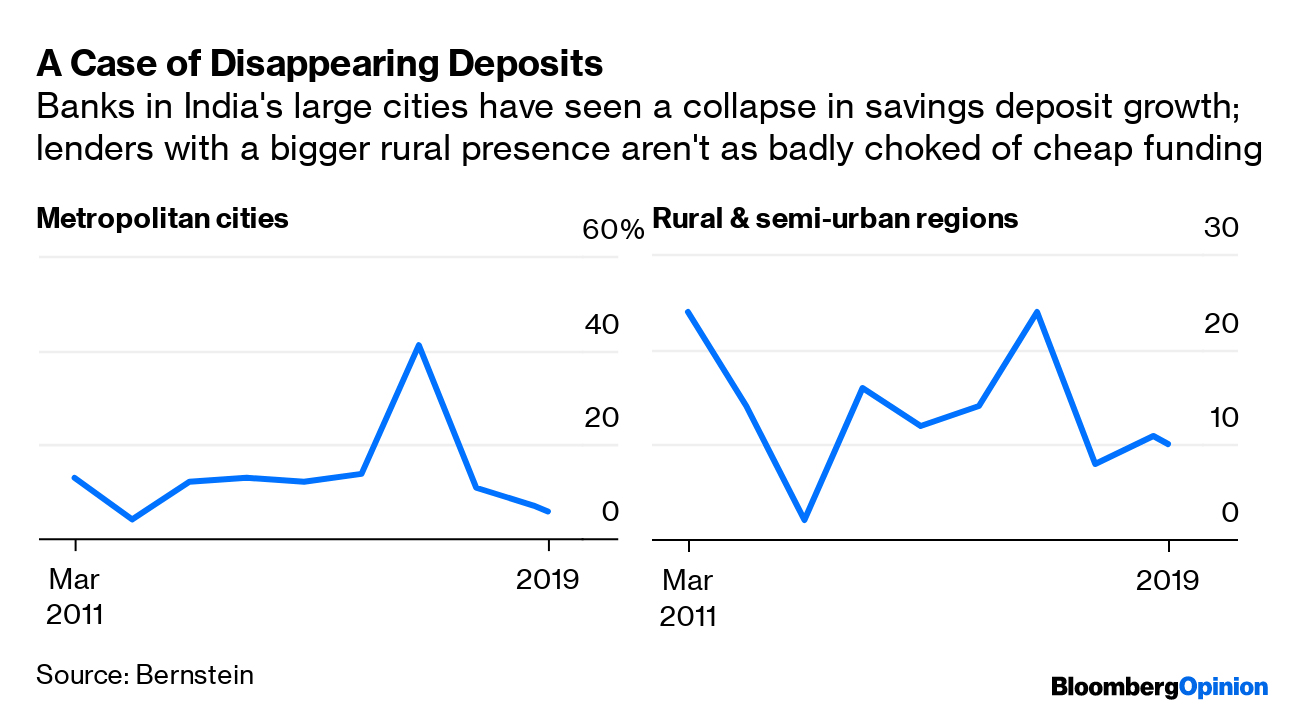

A surge in lower-quality customers would raise credit costs. It will be a double whammy when banks have to provide for bad loans after paying for costlier term deposits. And that’s linked to the consumption slowdown, because of what Bernstein analyst Gautam Chhugani calls the sheer “exhaustion of household savings in the large metropolitan cities.”

This is a true showstopper. Unlike their state-run cousins, HDFC Bank Ltd., ICICI Bank Ltd. and Axis Bank Ltd. are more city-centered lenders. Right up to March 2016, the trio enjoyed steady annual savings deposit growth in the range of 17%-18%. Then, in November that year, came the draconian Indian currency note ban. Their deposits swelled as people returned the 86% of the currency that was no longer legal tender.

But the top three banks’ savings deposit growth has since slipped to 10%, while for all lenders the figure has plunged to as low as 6% in metropolitan areas. Urban Indian consumers have reached into their nest eggs to battle sudden job losses, poor pay increases and a $15 billion wealth shock from apartments that they’ve paid for but were never built because developers ran out of money.

Having lowered their savings rate to 22% of disposable income last year from 29% in 2012, consumers are shopped out, as evidenced by the 41% fall in August car sales, the biggest drop on record. Not only is the slump bad news for vehicle finance, but the depressed consumer sentiment is a Catch-22 for unsecured lending.

As Bernstein analysts explain, 35% of HDFC Bank’s earnings growth comes from credit cards and personal loans. If the bank goes down to smaller cities and towns in search of the next borrower, it will be competing for the typical micro-finance customer. And this type of subprime borrower could already be in significant debt. Bandhan Bank Ltd., a small-loans specialist, has of late been making advances with an average ticket size of 64,000 rupees, ($890) compared with under 40,000 rupees on its outstanding micro loans.

Not wanting to go down this path will present the other challenge — of not being able to earn a decent margin on costlier term deposits. Either way, the prognosis for bank shareholders isn’t bright. A bigger worry is the macroeconomic impact of big private-sector banks stepping off the gas. Stricter standards could worsen India’s consumption slowdown by making unsecured credit harder to come by.

Sooner or later, stretched household finances will affect mortgage demand. That won’t help with India’s plan to get buyers back into the real estate market with deep interest-rate cuts.

Mind, there’s no sign of a subprime crisis. At least, not yet. But prime borrowers are few in a country where just 27% of the women aged above 30 are in the workforce, unemployment is at a 45-year high of 6.1%, barely 23% of workers earn a regular wage, and only three out of the 10 who enjoy a steady salary have proper job contracts.

Unsecured loans can only offer banks a temporary shelter during a downturn in collateralized credit. That protection doesn’t last long. –Bloomberg

Also read: Debt crisis has hurt India’s plans to have a bigger bond market