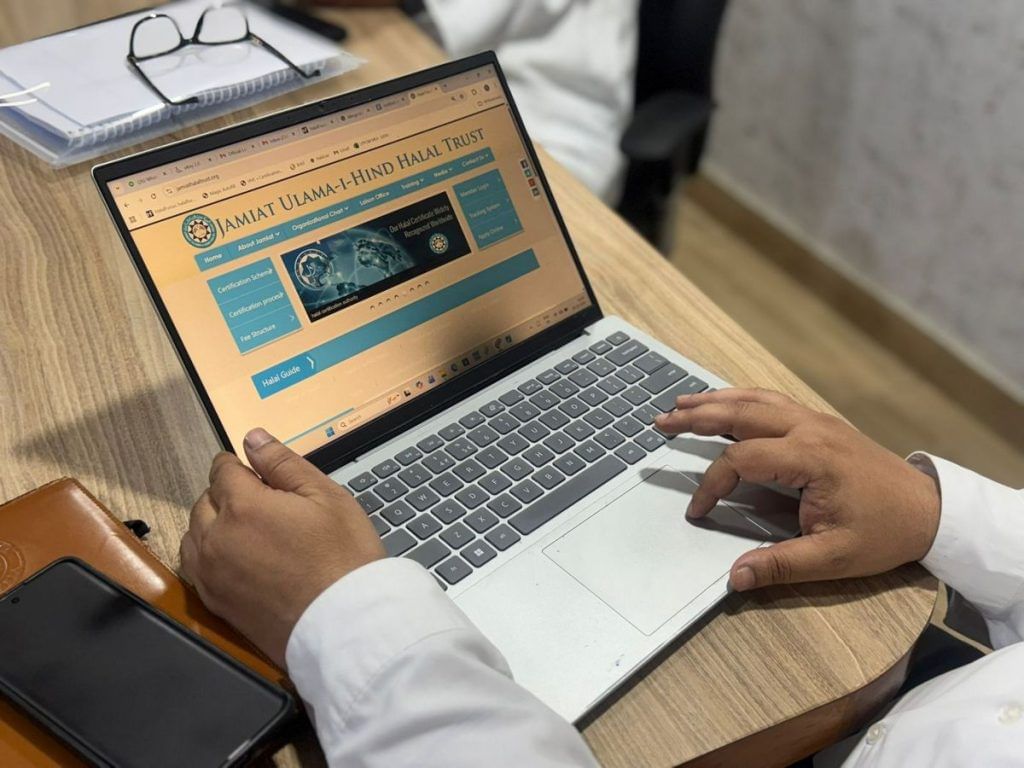

Delhi: There is a thick blue file named ‘halal certificate for cow ghee’. And it is lying on Niaz Ahmed Farooqui’s desk inside the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust office in New Delhi.

Phones ring non-stop, files shuffle from one table to another against the backdrop of feverish keyboard clickety clack. As the CEO of the trust, Farooqui has to authorise halal certificates for products as varied as aluminium foil products, potato chips, and even water bottles.

A Hindu businessman from Rajasthan wants halal approval for cow ghee headed to the Gulf market. Another, from Gurgaon, seeks clearance for a new lipstick line. “Does it comply with Shariah law?” Farooqui asks, flipping through the pages before signing.

Both products comply. The manufacturers want the halal certification. But there’s a catch. They don’t want the halal logo on the packet. There’s fear over Halal stigma that rules many Hindu minds these days and they want to escape political attention. A couple of weeks ago, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath alleged that money collected through halal certifications was being misused for “terrorism, love jihad and religious conversions”.

They want the certification for the boxes bound for the Middle East market but not on each pack.

“Businessmen are removing the logo these days because of political turmoil,” murmurs someone in the office, as the faint call of the afternoon azaan seeps in from outside.

“To make a shampoo, you need a concoction of about 20 ingredients. The source of each one is checked to ensure it is halal-compliant. It is almost like preparing for a school’s Annual Day — everything has to be spotless, organised, and perfectly in place.

-Exporter of halal-certified personal-care products

Even as the Uttar Pradesh government has once again stirred the halal ban debate, the demand for certification continues to grow quietly. The universe of halal products is massive, and India is a major player because of its export sector. And it is not just for meat products.

In 2024, the global halal food market was valued at around USD 2.7 trillion and is expected to reach USD 5.9 trillion by 2033. India’s exports of halal-certifiable goods to OIC nations alone amounted to USD 4.9 billion in 2023, up from USD 4.3 billion the previous year. Much of this trade is driven by non-Muslim businesses such as Tata, Hindustan Unilever, Jindal Steel, and even Patanjali.

“Indian halal-certified products are popular in the Gulf, the Middle East, Singapore, Malaysia, and similar markets. They trust our certification,” said Farooqui, who is also a Supreme Court lawyer and an Islamic scholar from Darul Uloom, Deoband.

India exports a diverse range of halal-certified goods to the Gulf, with buffalo meat, seafood, Basmati rice, honey, cosmetics, and personal care items among the most important categories.

But the certification that reaps profits abroad triggers anxieties back home.

Also Read: The GI tag man of India lives in Varanasi. He is blending culture and commerce

Pure business vs ‘pure politics’

At first glance, it’s pure business. But within India, this trade is fractured by politics.

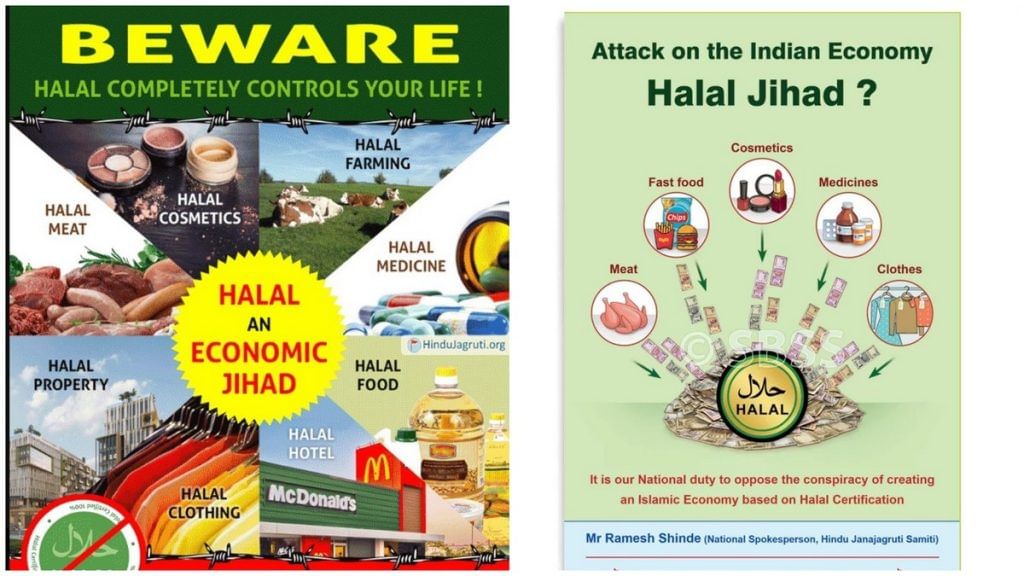

The word ‘halal’ is loaded. Global fast food chain McDonalds faced boycott calls in India when it announced all its meals were halal certified a few years ago, and now there’s a trend of online outrage over packaged brands featuring the label, from Aashirvaad Atta to Himalaya to Haldiram. Those offended warn Sanatanis to steer clear.

There are also rumblings that the halal certification business is a “scam” that only makes products more expensive.

From time to time, this concern has been amplified by the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister himself. Speaking at the RSS centenary event last month, Yogi Adityanath described halal certification as a parallel, unregulated system operating outside government control. He claimed it led to the “collection” of Rs 25,000 crore across the country, which was then funnelled into “conspiracies”.

It wasn’t the first time. In November 2023, the UP government banned the production, storage, sale, and distribution of halal-certified food products within the state — while exempting exports.

Those who run the halal certification business point out that the ban seems redundant, given that packaged items were only ever certified for the export market.

“These halal-certified products are only meant for Islamic countries. There was no demand from the government or the people for such certified products in India,” Farooqui said.

India cannot afford to ban halal exports. These exports earn billions of dollars annually. It is only for regional politics, to fool the masses

-Exporter of halal-certified packaged water

The political climate, though, has affected businesses. They are not breaking the law but are still feeling the heat. They have devised new ways to circumvent scrutiny. Many now use two sets of packaging, one without the halal certification logo for the domestic market and the other with it for export to Islamic countries.

Inside the factories, however, the production process remains Shariah-compliant: the halal way.

“It’s pure business. If you want to sell a product outside India, you need halal certification the way you need FSSAI or ISO within the country. So why would a businessman waste resources producing two lines — halal and non-halal? The industry is making so much profit for India that there’s no way they can ban it,” said a Hindu businessman from Chennai who sells wheat domestically and to Gulf countries.

He too applies for halal certificates and uses different boxes for the domestic and export markets.

Another Uttarakhand-based exporter who sells halal-certified packaged water to Islamic countries called the controversy “pure politics”.

“India cannot afford to ban halal exports. These exports earn billions of dollars annually. It is only for regional politics, to fool the masses,” he said.

When a ban crosses state borders

As soon as the Uttar Pradesh government introduced the ban on halal-certified products in 2023, its impact travelled way beyond the state’s borders.

In Bengaluru, a mid-sized cosmetics manufacturer who had spent 10 years building his business faced the first ripple effects. Retailers and distributors in Uttar Pradesh who had traded with him for over five years suddenly began turning him away.

“There was a lot of apprehension. It was not as if police were coming and vandalising shops, but the fear that it might happen made them reject such products,” said the businessman, a Hindu in his late 50s who also exports skincare products to markets such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar, and Kuwait.

Despite his efforts to reassure partners, rejections and cancellations piled up. He then diverted his stock to Madhya Pradesh, where the ban wasn’t in place, but met the same response there as well. The pattern repeated when he tried the Maharashtra market.

With no buyers and storage costs mounting, he decided to destroy the unsold domestic inventory, valued at several crores of rupees, within months of the ban as he was unable to divert them to his export clients. The financial setback was severe. In his decade in the cosmetics industry, he said he had never encountered such a situation before.

“My products always had a halal-certified logo, and it was never a problem. I just wanted to be true to the customers. If I was making products through the halal process, I wanted them to know,” he said. “I never knew that my transparency toward my customers would cost me.”

It’s nearly a month-long process of proper scrutiny — from inspecting facilities and tracing ingredient sources to consulting top Islamic scholars — before a product is granted halal certification

-Noman Lateef, general manager, Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust

Like many other manufacturers, he got the certification for his exports and thought nothing of using the label domestically too. Last year, he decided to try a new strategy. For the domestic market, he removed the halal certification logo from his packaging. The two sets of packaging increased his production costs by almost 10 per cent.

But inside the factory in Bengaluru, nothing really changed. The same raw materials, the same careful formulations, the same process continued — all compliant with halal standards.

The only difference was the label. The packaging just stopped screaming it out loud.

There was no question of making any process changes. Earning a halal certificate and passing stringent checks is no easy task.

What do halal trusts do?

Halal is not just about meat or how an animal is slaughtered. It extends far beyond that, into the hallways of production houses and factories, where even the minutest detail matters. It’s not just the product; the entire manufacturing process has to be Shariah-compliant. This is where certification officers act as the new Halal Inspector Raj.

A single strand of hair, a bottle of alcohol, or a dog curled up to sleep within factory walls can turn a product non-halal.

There are multiple Halal certification bodies in India, including the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust, Halal India, Halal Trust India, and IS EG Halal India Pvt Ltd. An entire industry of scholars, scientists, and safety inspectors is involved.

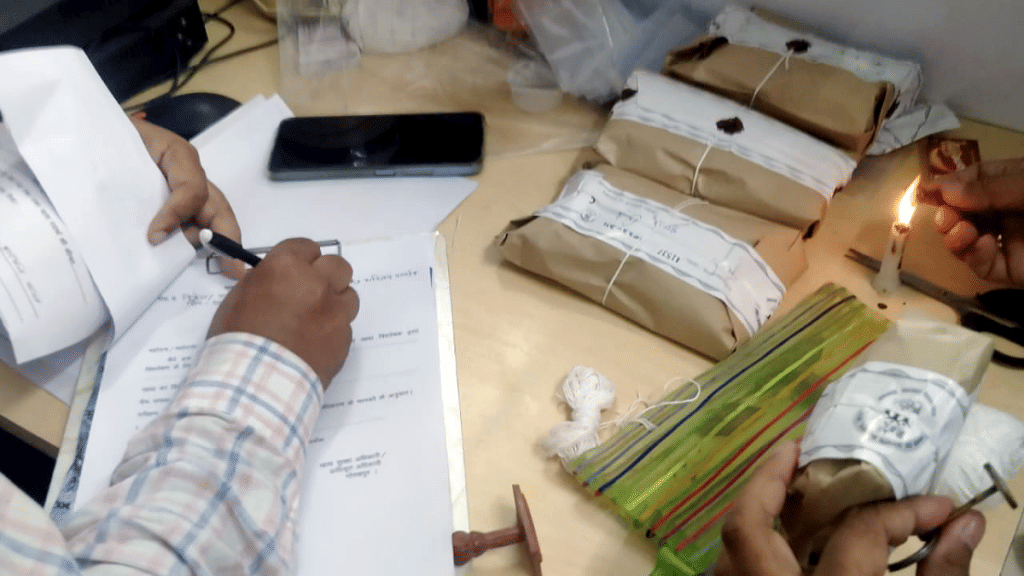

Each applicant submits detailed paperwork, from ingredient lists and production flow charts to lab reports from FSSAI-approved or NABL-accredited facilities. Inspectors visit factories to verify hygiene, sourcing, and storage, and after certification, products face regular audits and random testing.

At the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust office, the journey of each product into the halal world goes through two phases. First comes the technical team, which examines the paperwork. Then it moves to the Shariah team — a group of Islamic scholars who dive into the heart of the production process. They break down the product’s composition to verify that every ingredient is Shariah-compliant.

“If a product contains pork, animal fat from non-halal sources, alcohol, human hair, or the excreta or urine of humans or animals, it is considered non-halal,” said Farooqui, head of the Shariah team, adding that even Patanjali obtained its halal certification for export goods from them some years ago. This decision set off a controversy in 2020 among Muslims due to the alleged use of cow urine in some products. The trust, however, said every stringent guideline had been followed.

The meat that reaches your table should be fresh, disease-free, and safe to eat. Around 60 out of 70 slaughterhouses in India take certification from us, mostly in UP. We have our supervisors deployed at these facilities to check whether halal practices are being followed

-Niaz Ahmed Farooqui, CEO of Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust

“If some people have objection that we have certified a company owned by a Hindu, let me clarify that we can certify any company which produces Halal product regardless of their caste, creed or religion,” said a statement issued by the trust at the time.

Whether it is processed buffalo meat, a packet of chips, or a shampoo, the inspection preparation starts well before the team visits.

“It’s nearly a month-long process of proper scrutiny — from inspecting facilities and tracing ingredient sources to consulting top Islamic scholars — before a product is granted halal certification,” said Noman Lateef, general manager, Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust. Normally, a team visits the facility and inspects the entire area for a full day before moving to the paperwork.

The inspection process

For a business, the days leading up to the halal certification visit are always tense and busy. Long before the Shariah team arrives, the staff begins checking every ingredient, every label, and every process to make sure everything is in order.

Any mistake and halal export dreams are benched.

Even something as simple as a packet of chips goes through the halal certification process. Every detail is checked — from the oil used to fry the chips to its source. If animal fat is involved, the technical team ensures it comes from a halal-certified source.

In the case of meat, getting the animal halal-ready entails several steps.

Before slaughter, the animal is fed nutritious food and its body and organs are thoroughly checked for any signs of injury or disease. When it comes time for slaughter, it is taken away from the sight of other animals.

“The meat that reaches your table should be fresh, disease-free, and safe to eat. Around 60 out of 70 slaughterhouses in India take certification from us, mostly in Uttar Pradesh, especially Aligarh,” said Farooqui. “We have our supervisors deployed at these facilities to check whether halal practices are being followed.”

The owner of a frozen meat business in Uttar Pradesh recounted that the Shariah team didn’t just investigate his unit. It first visited the slaughterhouse where the meat was slaughtered. From there, they went on to the facility where the packaging of the frozen meat was done before it was sent out to the stores.

It’s pure business. If you want to sell a product outside India, you need halal certification the way you need FSSAI or ISO within the country. So why would a businessman waste resources producing two lines — halal and non-halal?

-Chennai-based wheat exporter

“The entire process took about a week, during which the Shariah team carefully inspected every stage. Only after completing their thorough review were they satisfied with the halal nature of the meat,” said the owner, a Hindu who exports his products.

For the Bengaluru-based businessman, getting his shampoo certified halal was headache-inducing. Every ingredient had to be verified.

“To make a shampoo, you need a concoction of about 20 ingredients. The source of each one is checked to ensure it is halal-compliant,” he said, adding that every scrap of paper was carefully scrutinised. Probing questions are asked about the manufacturing process, down to the cleaning materials used. “It is almost like preparing for a school’s Annual Day — everything has to be spotless, organised, and perfectly in place.”

Also Read: Here’s how Khilji, Akbar, and Hindu rulers dealt with Halal

Battle of certificates—Halal, Malhar, Om

Halal meat and products have long been a point of contention for India’s right wing, and those concerns found new expression after the Yogi Adityanath government’s crackdown.

Businessmen in the state say it’s largely posturing and that exports continue “seamlessly”.

The problem is what the political rhetoric does to the public mood. It has created fear and aversion among traders and storekeepers about halal certification. Many of them do not have all the facts about the process or the rationale for it.

Clients of the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust are now facing the heat. A few claimed government agencies have begun interrogating them about the source and use of funds from the sale of halal-certified products. Adityanath’s claim that “Rs 25,000 crore” was generated through certification and put to nefarious use is also haunting certifying bodies.

“We barely charge Rs 20,000-30,000 for one halal certificate. There are three major certification bodies — one in Maharashtra, another in Chennai, and one in Delhi. The total revenue of these three bodies is around Rs 7-10 crore. So the figure mentioned by the UP CM of Rs 25,000 crore doesn’t hold water,” said an employee at the Halal Trust.

While Halal certification has been around since the 1970s, its scope expanded significantly after economic liberalisation and the widening of exports to global Muslim markets. The system is run largely by independent trusts and NGOs with minimal government oversight. The Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind Halal Trust, set up in 2009 as a charitable arm of the Muslim NGO Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, currently has 14 members, including chairman and former MP Maulana Mahmood Madani, CEO Niaz Ahmed Farooqui, along with muftis, maulanas, and technical experts.

With halal logos appearing on more non-meat products, social media has become a battleground for debates. Some users call for a complete ban on halal certification; others demand a Hindu alternative.

“If you want halal, then we have to go with our own ॐ certificate,” wrote X user Shravan Bishnoi, a self-professed “Globalist- Hard-core Bhartiya /Hindutva” with around 24,000 followers.

This idea of an “Om certificate” has been gaining traction since last year, with Hindu organisations raising it aggressively.

In June 2024, at the Vaishvik Hindu Rashtra Mahotsav, halal certification was described as the “economic jihad route to Islamisation of India.” A protest was taken out against the “menace of halal imposition on all products”. Om certification was suggested as a counter, with several Hindu shopkeepers adopting it, not just in UP but also Maharashtra. Last November, amid criticism over “halal imposition”, Air India announced a new policy of putting the halal-certified label only on ‘Muslim’ meals on Gulf-bound flights and not those meant for others, whether veg or non-veg. It was widely lauded on social media as satisfying the demand for “jhatka” non-veg.

The anti-halal sentiment is now bubbling in several states. Last week, Jammu-based activist S Sushil Singh Charak wrote to the Lieutenant Governor and Chief Minister urging a ban on halal meat in government institutions and a uniform food policy for the Union Territory.

In March, Maharashtra fisheries minister Nitish Rane launched a campaign for “Malhar certification” in Hindu-owned meat shops.

“Today we have taken an important step for the Hindu community from Maharashtra… Hindus will get access to mutton shops selling Jhatka mutton,” he wrote on X.

But for small shopkeepers in the narrow lanes of Old Delhi, halal certificates have no meaning. Their halal certificate is their Muslim markers—the skullcap and long, wavy beard.

“We sell biryani here in the vicinity. Everyone knows me. And my cap is the real halal certificate,” said Mohammad, who has been running his business for the last 20 years near Jama Masjid.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)