Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

Part II

Continued from Part I

The 16th-century Vaishnava resurgence in Bengal witnessed the Vaishnava Padabalis alongside the Shakta texts. Shakta Padavali features the poet and the Goddess as central figures, with Kali reimagined as Shyama. Sukanya Sarbadhikary explores the ‘Krishna-Kali’ connection, highlighting literary archetypes rooted in regional philosophy that reveal subtle traditions of deity equivalence. The domestic worship of the goddess introduced by Agamabagish resonated deeply, gaining momentum with the patronage of Raja Krishnachandra of the Nadia Raj, also a devout Shakta. Around this time the Mangal Kavyas were becoming noteworthy compositions referring to the contemporary social-cultural upheavals; the kavyas not only entrenched the goddess in Bengal’s religious landscape but also facilitated her enigmatic presence beyond the region, as traders and merchant guilds carried her legend along with their commerce. Annadamangal, a text in the Mangal Kavya tradition written by Bharatchandra Ray in 1752, further reinforced the goddess in mainstream religion. As the court poet of Raja Krishnachandra, Ray’s work had significant repute. Rachel Fell McDermott highlights the intense portrayal of the goddess around this time through devotional poetry, rituals, and festivities. McDermott emphasizes the tradition of goddess worship getting strengthened in the 18th century through the compositions of Shyama Sangeet. Ramprasad, a devout Shakta poet and disciple of Agamabagisha, composed these songs that played a pivotal role in bridging the gap between the goddess and her devotees. His lucid compositions, infused with metaphors from daily life, reverberated with the masses, particularly the larger agricultural communities. Ramprasad made the goddess relatable and tangible, allowing devotees to approach her with mundane problems and concerns. Images, rooted in the agrarian landscapes, helped to convey complex spiritual ideas in a simple yet profound manner. Through his songs, Ramprasad connected the paradoxes of Kali’s nature, depicting her as a loving mother, a compassionate daughter, and a loyal companion. He emphasized the personal bond between the devotee and the goddess, making ‘Kali’ a quotidian goddess who could be approached with self-surrender, intimacy, and faith.

The rising popularity of the goddess during16th-18th centuries is to be visualised as a response to the socio-political disorders of the time. Bengal’s transition under the command of the Islamic expansionists and the British colonisers created an environment of uncertainty and chaos. In this context, Kali, with her ambivalent nature emerged as a powerful symbol of protection, strength, and salvation. Given the goddess’s widespread popularity among the masses, she likely served as a counter-hegemonic force, embodying a maternal figure who could protect her devotees from perceived external threats and internal strife, while addressing the everyday troubles. Her potential force reflects the complex interplay between religion, politics, and culture in shaping the spiritual and social landscape of early modern Bengal. British colonial authorities began to perceive the goddess as a frightening emblem of native society. From the early 19th century, she was linked to criminal and subversive groups like the notorious Thuggees, extensively discussed in colonial reports. These fears intensified with the rise of the revolutionary nationalist movement in Bengal, often believed to be spearheaded by secret societies under the goddess’s patronage. By the dawn of the 20th century, Kali’s image had captivated Victorian popular culture, symbolizing the dark, terrifying, yet strangely alluring powers of the Orient, as Hugh Urban puts it.

David Kinsley, in his account of the goddess, explores that the final chapter in her ‘taming’ is undertaken by one of her ardent devotees, Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna’s approach to Kali was marked by childlike simplicity, eagerness, and devotion. As a priest at the Dakshineswar temple where he joined in 1855, Ramakrishna experienced a deep spiritual awakening, convincing many that Kali was a living mother who could be approached for all difficulties. Ramakrishna’s experiences weaved the impersonal Absolute (Brahman) and the personal ‘divine’ mother, allowing him to see his life’s purpose as fulfilling Kali’s will and seeing the promise of immortality in her presence.

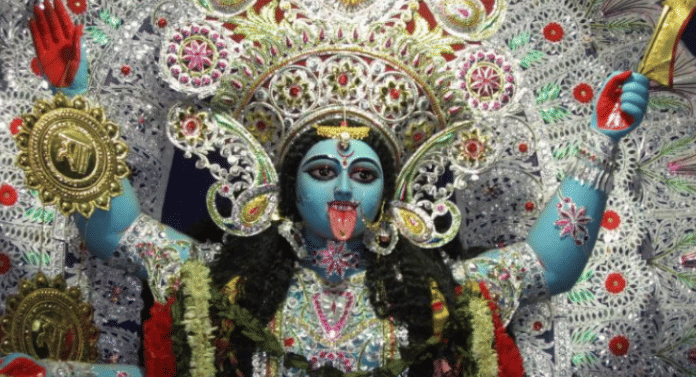

In eastern India, Kali continues to be deeply venerated. During Deepavali, devotees connect with the goddess’s profound aura, revering her dark form as a fierce protector who vanquishes evil, allowing probity to prevail. The festival’s lights celebrate this triumph, with earthen lamps lit to honour the victory over darkness and seek blessings. As the goddess of time, Kali’s might also resonates with the lighting of lamps, guiding departed souls who may visit during this time. The image of Samsan Kali at Keoratola Maha-Samsan, with her contained tongue, remains intriguing, despite her dominant form with the protruded tongue being well-known. This depiction belies her fierce reputation, revealing a deeper truth – that she embodies both destruction and renewal, time and timelessness. She stands tall, a beacon of calm, ushering us on a transformative journey from darkness to light, ignorance to knowledge, and sorrow to bliss. Her protective grace keeps us safe from harm, steering us toward a path of righteousness.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.