Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

In the life of any political community, the practice of mourning is more than an emotional ritual—it is a revelation of the society’s ethical priorities. Who is remembered and who is forgotten? Who elicits grief and who is passed over in silence? These are not secondary questions. They lie at the very heart of a polity’s claims to justice, dignity, and moral coherence.

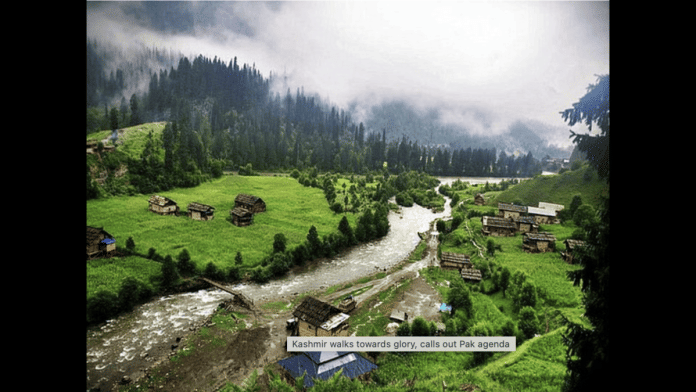

Nowhere does this moral economy feel more ruptured than in Kashmir. Over the last three decades, the region has witnessed extraordinary suffering: civilian deaths, institutional violence, broken families, and public workers executed for performing ordinary civic duties. Yet amid this disorder, one pattern remains consistent—the public, political, and intellectual frameworks that guide our mourning are profoundly asymmetrical.

It is not difficult to observe this asymmetry. On the one hand, individuals historically implicated in political violence receive attention, advocacy, and symbolic protection from the political class when they suffer or are incarcerated. Their illness becomes a cause. Their treatment in custody, a matter of public concern. Their names are spoken, their dignity affirmed. This concern may well be justified in principle—constitutional morality does not extinguish itself behind prison walls. The deeper issue, however, is not that these individuals are remembered, but that those who died sustaining the idea of public order are categorically forgotten.

The public servant gunned down while securing an election booth, the teacher shot in front of students for refusing to flee, the young constable killed by an improvised explosive device while conducting routine duty—these are not abstract statistics. These are stories of individuals who did not wield the language of violence, but who were met with it. They were not combatants; they were facilitators of the daily life of society. And yet their deaths have evoked no collective mourning, no letters, no demands for justice, no memory. Their families grieve alone, outside the frame of political language.

What explains this silence? Why is there no vocabulary of grief for these lives?

The answer lies in the gradual collapse of moral universality in the language of politics. Grief, which should be a moral constant, has become contingent—tied not to the nature of death, but to the narrative it can serve. If a death confirms a larger story of marginality, or victimhood, it is sacralized. If a death complicates that narrative—because the victim upheld the legitimacy of the state or represented a public institution—it is conveniently ignored. In this epistemology of mourning, the constable’s death is not politically useful, and is therefore ethically disposable.

This is not merely a problem of public relations, but a conceptual and ethical failure. The credibility of a democratic order rests not on how it protects ideological consensus, but on how it treats contradiction. A state that cannot mourn its own servants with dignity, and a political class that selectively remembers its victims, together produce a society that lacks the moral confidence to sustain itself.

The asymmetry is particularly stark when seen through the prism of political response. When a person in custody falls ill, politicians write to the Home Ministry, journalists raise the issue, and civil society mobilizes support. This may well reflect a commitment to human rights. But when a schoolteacher is shot in front of students or a policeman or a CRPF personnel is ambushed on duty, there is only silence. No editorials. No symbolic protests. No political mobilisation. The state may occasionally offer compensation, but even that is transactional, not memorial. There is no infrastructure of dignity around their deaths.

Ernesto Sabato once said: “There is no greater crime than to murder someone and then erase the memory of their existence.” This is precisely the quiet violence at work here: the terror of erasure masquerading as neutrality. To be forgotten is not merely to be ignored; it is to be stripped of one’s claim to personhood.

It is important to ask: what are the consequences of this moral selectivity?

First, it degrades the very idea of justice. When grief is unevenly distributed, so too is our conception of who deserves protection, memory, and voice. It turns justice into a commodity of political alignment rather than a principle of shared humanity.

Second, it erodes public trust in institutions. Those who serve the state—and more importantly, those who serve the people through the state—do so believing that their life and labour matter. When their deaths are erased, the implicit contract between society and its servants is broken.

Third, and perhaps most fatally, it leads to a culture of moral relativism, where the line between victim and perpetrator is drawn not by ethics, but by convenience. This opens the door to legitimising forms of violence that claim moral high ground but refuse moral introspection.

In this context, the recent efforts by the Lieutenant Governor’s administration to rehabilitate families of terror victims deserve attention—not as acts of state benevolence or charity , but as a modest restoration of civic memory. For years, their blood dried in silence. No outrage. No remembrance. A state that forgets its fallen weakens its own foundation. Justice, in such cases, does not lie in monetary compensation alone; it lies in recognition, in narrative, in the act of saying: “Your loss mattered.”

But the question remains: why did this recognition take decades? Why was the political class—across ideological divides—so reluctant to acknowledge the public servant as a victim? Is it because to do so would destabilise a narrative in which the state must always be the aggressor, and all who serve it must be seen as enforcers, not enablers?

Such a view betrays a profound misunderstanding of how societies function. Public order is not simply a tool of state control—it is the condition of democratic life. Teachers, panchayat workers, and police constables are not symbols of oppression. They are the quiet custodians of daily normalcy, without which liberty is meaningless.

To ignore their deaths is not just a political omission; it is an ethical collapse.

Avishai Margalit once said, “A decent society is one that does not humiliate its members.” In Kashmir, the greatest humiliation is posthumous: to be killed in service of society, and to be erased from its conscience. This is not a lapse in mourning—it is a structural act of forgetting.

If Kashmir is to move towards a more just, inclusive, and mature political order, it must first restore moral clarity to its memory. That means grieving all lives lost—regardless of political convenience. Some deaths reflect deep wounds in our collective conscience; others speak of quiet resilience that kept the social fabric from tearing apart. In remembering them all, we do not indict—we humanise. Dignity is not a concession to be granted by power; it is a truth carried by the people, even in their silence.

As Jean Amery—once wrote, “To be a victim is to be robbed of both future and remembrance. The dead suffer twice: in dying, and in being forgotten.” In Kashmir, many have suffered that second death—the slow erasure of meaning in a society that reserves its grief for the politically convenient.

A state that cannot remember its dead with dignity cannot command loyalty with integrity. And a society that cannot mourn without bias will remain locked in a politics of selective pain, where justice becomes performance, and grief becomes propaganda.

By: Zahid Sultan ( Freelance Researcher: PhD in Political Science)

Email: Zahidcuk36@gmail.com

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.