Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/

The right to life and personal liberty is incorporated into the Constitution of India under Article 21 which forms the moral centre of Indian democracy. However, this provision has become a regular bone of contention between the state authority and citizens’ right to freedom.

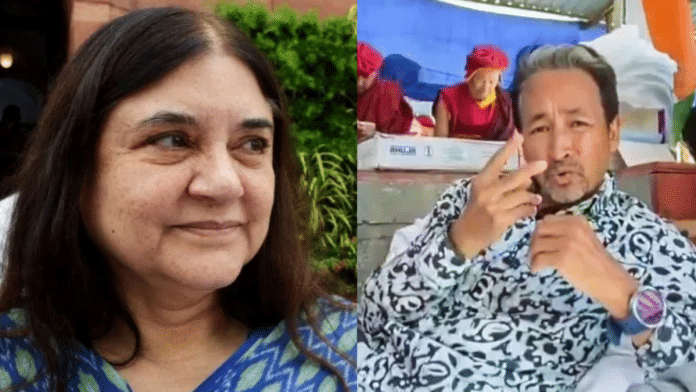

As the decision of the Supreme Court in the Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) was lauded as a constitutional landmark that introduced the principle of “due process” to Indian jurisprudence , the rule by one government after another, showed reversal to the earlier principles of “procedure laid down by law”.

The principle of “procedure laid down by law” indicates that any conviction is legitimate as long as it happened under a law passed in the parliament following proper procedure. This principle is enshrined in Article 21of Indian Constitution. On the other hand, “due process”, which was borrowed from the American system, adds the criteria of justness, fairness and reasonableness to the law.

Maneka Gandhi’s passport was confiscated unduly without giving her proper reasons. Passport Authority of India informed her only that it was in public interest. Maneka Gandhi appealed to apex court on grounds that it violated her fundamental rights under Article 14, 19 and 21. The ruling in this case held that laws enacted by the Parliament should should follow “due process” and the three articles on fundamental rights should be read together.

Fast forward four decades, the increasing incidence of the prevention detention legislations and the curbing of the voices of unwelcome opinion portrays a democracy that follows the formula of a procedure that is laid down by law and not due process.

What started as a court victory, has not been converted into realpolitik. The growing overreach of executive in the name of security or national order goes to indicate that the spirit of due process is still weak.

The National Security Act (NSA) and Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) have been applied with frightening frequency not to be used to combat terrorism per se, but to police dissent and political opposition. The fair, just and reasonable principle of treatment has been replaced by convenience in the administration and political expediency.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) and the regular internet blackouts in places like Manipur and Jammu and Kashmir shows how legality is being pushed to interrupt participation and accountability. Moral scrutiny is defended by the compliance by the government procedures that prove that the procedure developed by the law has been turned into the alternative of justice and not the tool of it.

World Governance Indicators (WGI) shows that India slid 10 points down in 10 years (2013-2023) from 61.5% to 51.47% on Voice and Accountability. Although remained in the range of 51-53 percentage points on rule of law, tolerance for dissent has reduced significantly post-2014.

The latest example of due process in modern India is the recent arrest of Ladakhi climate activist Sonam Wangchuk on National Security Act. Although Wangchuk was reputed as a peaceful reformer, he arrested after the protesters insisted on constitutional protection and statehood of Ladakh. The state defended the move as being a part of the procedure of the NSA, but multiple procedural flaws were apparent.

He was not immediately told the reasons of his detention. He was not allowed access to legal counsel and contact with his family. The fact that he was moved to Jodhpur Central Jail, which was several hundreds of kilometres off, denied him fair representation and dignity.

This episode reflects a larger trend of law as a tool of authority and not a guardian of rights. The explanation of the arrest of activists, journalists and students under the generalized security provisions is indicative of a state that has perfected the art of legality with no legitimacy. This trend is not an occasional but a systematic process now.

This transformation shows a different form of authoritarianism under the guise of procedural compliance. With every detention, which has been supported by the technical legality, the promise of substantive justice as Maneka Gandhi had envisaged gets eroded. The outcome is a system where legality and lack of liberty coexists. Democracy is just a ritual.

The transition from A.K Gopalan to Maneka Gandhi was to change India into a constitutional democracy that was based on fairness and justice. However, the arrests of activists such as Sonam Wangchuk indicate that the Gopalan spirit is still present. India still practices procedures set up by the law without considering due process of law.

Swetasree G. Roy, Professor of Political Science at Jindal School of Government and Public Policy; Adhiraj Verma, student at Jindal School of Government and Public Policy.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.