Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/

“The ’91 reforms were relatively easy because they involved getting the government out of things it shouldn’t do. However, the next generation of reform will focus on making the government better at doing things it has to do.” — Montek Singh Ahluwalia

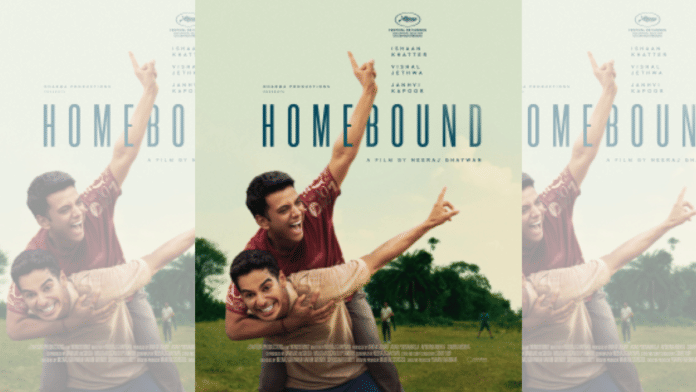

Neeraj Ghaywan’s Homebound is not a sermon. It isn’t even, strictly speaking, political cinema. Yet beneath its quiet narrative of two friends navigating caste, faith, and circumstance lies a subtle but sharp indictment of the Indian state — and an urgent call for what Ahluwalia describes above.

At its heart, Homebound follows Chandan and Shoaib, two young men who see the police uniform not merely as a job but as an escape — a shield against the prejudice that defines their lives. The uniform, for them, is dignity and access. The film never spells this out, but it makes one point clear: when state institutions work, they shape destinies.

The movie shows state failure without naming it. A lockdown separates families. A sister is denied education because survival demands sacrifice. A young man hides his caste to avoid humiliation. When public systems falter, people improvise. They walk, queue, bribe, and hide. This is the reality of what economist Lant Pritchett calls a “flailing state” — where policies exist, but implementation thrashes about ineffectively.

A Pandemic Stress Test

The pandemic was the most brutal stress test of this flailing state. We saw migrant workers walking home because transport shut down overnight, families begging for oxygen online, and bodies piling up outside hospitals. And yet, when asked in Parliament how many migrants died during the lockdown, the government replied: “No such data is available.” It offered the same answer on job losses.

The World Bank estimates that the lockdown affected the livelihoods of nearly 40 million internal migrants. Over 63 lakh workers were transported on 4,611 Shramik Special trains, but at least 110 died during the journeys. Daily wage earners, 32% of India’s workforce, suffered 75% of the employment hit in April 2020. Yet the state recorded none of this.

This absence of data was not accidental — it exposed a state struggling with basic capacity: poor data systems, weak coordination, and fraught public–private cooperation. As one of India’s leading development economists, Karthik Muralidharan, notes in Accelerating India’s Development: A State-Led Roadmap for Effective Governance, the pandemic laid bare the costs of weak capacity. “The elites and middle classes,” he writes, “are like business-class passengers on a crashing plane. They may have islands of comfort, but the plane’s failure will take everyone down.”

Leaking Trust: The Exam Saga

The story repeats elsewhere. In recruitment exams across 15 states, at least 41 leaks affected 1.4 crore applicants competing for just 1.04 lakh posts, according to The Indian Express (Feb 6, 2024). Some candidates still await re-examinations. In Telangana, 3.8 lakh aspirants from a 2022 exam remain in limbo. In Gujarat, 6 lakh candidates waited over two years for a re-test.

These are not minor lapses; they are breaches of trust. A state that cannot conduct a fair exam or deliver basic services reliably undermines faith in its legitimacy. For the marginalised, that failure is not an inconvenience — it is catastrophic.

The Health System’s Uneven Pulse

Health is another reminder. During the pandemic, combined health spending rose from 1.4% of GDP (2017–2020) to 1.9% in 2022–23, but still missed the 2.5% target set by the 2017 National Health Policy (IMPRI, Feb 20, 2025). Budget growth slowed to just 0.4% in 2024–25, and massive funds — ₹47,500 crore under Jal Jeevan Mission and ₹*2,800 crore under Swachh Bharat Urban — went unspent.

India’s infant mortality rate, though down from 142.6 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to 28.3 in 2019, remains over four times China’s. Life expectancy trails China by 7.3 years, and 34.7% of children are stunted — 4.3 times China’s rate. These are not mere statistics; they are stories like Chandan’s and Shoaib’s — of denied dignity and broken promises.

Why State Capacity Matters

Karthik Muralidharan, in Accelerating India’s Development: A State-Led Roadmap for Effective Governance (2024), argues that investing in state capacity yields far higher returns than conventional spending. A call centre for Telangana’s ₹10,000 crore Rythu Bandhu scheme delivered ₹25–₹100 more to farmers for every ₹1 spent. A biometric payment system in Andhra Pradesh cut NREGS leakages by ₹200 crore and saved ₹25 crore in time — a 10× return. Regular school monitoring cuts teacher absence by 25–40%, more cost-effective than hiring more teachers.

These examples shift the debate from allocations (“top line”) to outcomes (“bottom line”). Building capacity — better data, incentives, and institutions — turns budgets into results, laws into justice, and rights into reality.

From Flailing to Functioning

There is hope. India delivered over 1 billion vaccine doses in just six months in 2021, proving the state can perform when it chooses to. But competence must extend beyond crises. Governance shapes lives daily; failure costs millions. India doesn’t need a minimalist state but a capable one — focused, effective, and strong where it matters most. Because when the state works better, everything works better — and that is the unfinished project of Indian democracy.

Cited Sources:

- The Indian Express, “The Big All India Exam Leak: Over 5 Years, 1.4 Crore Job Seekers in 15 States Bore the Brunt” (Feb 6, 2024)

- IMPRI – Impact and Policy Research Institute, “From Pandemic to Progress: Where Does India’s Health Budget Stand in 2025?” (Feb 20, 2025)

- Karthik Muralidharan, Accelerating India’s Development: A State-Led Roadmap for Effective Governance (Penguin Random House India, 28 March 2024).

Sai Manikanta Thota, holds a PGP in public policy from Indian School of Public Policy

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.