Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

Beyond the Mughal Myth

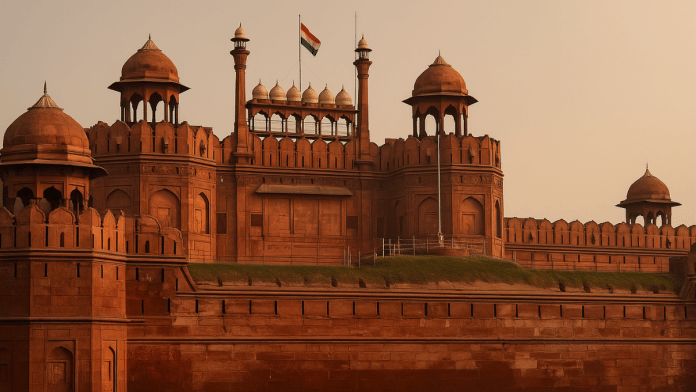

Each year on 15 August, the Prime Minister hoists the national flag from the ramparts of the Red Fort. In public memory, this monument is the pinnacle of Mughal grandeur, a Persianate jewel in red sandstone, born of Shah Jahan’s vision. But the historical and archaeological record tells a more complex, and to my mind, more compelling story.

From a structural and technological standpoint, the Mughal Red Fort is not an isolated Persian-Central Asian creation. It is the latest monumental expression of a fort-building tradition rooted in the Indian subcontinent since at least the Tomar period. The Mughals did not bring large-scale stone fortification technology from their homeland in Central Asia. They inherited, adapted, and refined an indigenous architectural lineage that runs from Lal Kot in the 11th century to Qila Rai Pithora in the 12th, through the Sultanate forts of the 13th–16th centuries, culminating in the Red Fort of the 17th.

The First Red Fort of Delhi

In 1052–60 CE, the Tomar ruler Anangpal II built Lal Kot on the Delhi ridge, a citadel with 3.6 km of stone ramparts, semi-circular bastions, and strategic gateways like the Ghazni Gate. Excavations in the 1990s led by B.R. Mani revealed two key occupation phases: a Rajput period with trabeate stone gateways and robust masonry, and an early Sultanate phase that reused the same fortifications.

Lal Kot was Bharat’s “first Red Fort”, red not from Mughal sandstone, but from Delhi quartzite. It was conceived in the tradition of Rajput hill forts like Chittorgarh and Gwalior, integrating defence with political symbolism. In contrast, the Mughal ancestors in Ferghana built with mudbrick and timber; the technology of ashlar masonry, corbelled arches, and bastioned walls was already a mature Indian craft when the Mughals arrived centuries later.

Qila Rai Pithora and the Sultanate Forts

In the late 12th century, the Chahamanas under Prithviraj III expanded Lal Kot into Qila Rai Pithora, extending the enclosure to 6.5 km. The layout, high stone curtain walls, projecting bastions, controlled entry points, became the template for Delhi’s fortified capitals.

Successive Delhi Sultanate rulers-built Siri, Tughlaqabad, Jahanpanah, and Firozabad on the same principles, modifying materials and ornamentation but preserving the core engineering logic. The fort was not just a military structure; it was a palace-city, housing the court, administrative offices, and urban population within its walls.

The Mughals and an Inherited Technology

When Babur entered Delhi in 1526, he found a city whose political heart was already defined by this indigenous fortification tradition. Neither Babur nor his Timurid forebears had any tradition of monumental stone forts; their Central Asian strongholds were built for different geographies and materials.

The Mughals inherited a well-developed fort-building system and the artisanal communities that sustained it. By Akbar’s time, at Agra Fort, the synthesis was explicit: indigenous engineering married to Persianate decorative idioms. Shah Jahan’s Red Fort would be the most refined iteration, but structurally it followed the same Indian template.

The Red Fort: Culmination, Not Creation

Built between 1638 and 1648, the Red Fort’s rectangular plan, bastioned walls, and inner palace precinct recall not just Agra Fort but Lal Kot and Qila Rai Pithora. The ceremonial axis from the Lahori Gate to the Diwan-i-Khas mirrors earlier processional routes. The Nahr-i-Bihisht, a water channel flowing through the palace, extends a tradition of integrating waterworks into royal architecture, visible in the Anang Tal reservoir and Sultanate hydraulic systems.

Even its name, Lal Qila, echoes Lal Kot. The “red” was now Mughal sandstone, but the fort’s DNA was local.

The Indigenous Hand Behind the Mughal Facade

Abu’l Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari records that the Mughal imperial workshops employed thousands of Hindu stonecutters, masons, and carvers, particularly from Rajasthan and Gujarat. These were the descendants of the same guilds that built Rajput forts and Delhi’s earlier citadels.

The Mughals added Persianate elements, cusped arches, marble inlay, charbagh gardens, but relied on Indian engineering for the core structure. The outer ramparts of the Red Fort could have been built by Anangpal’s masons; the continuity of skill and technique is that strong.

Why This Continuity Matters

To reframe the Red Fort as the culmination of a millennium-old indigenous tradition is not to deny the Mughals their artistry. It is to acknowledge that architectural history in India is a continuum of adaptation and innovation, not a series of disconnected “imports.”

This recognition also challenges the habit of assigning monuments exclusively to dynasties, as if each regime built in isolation. The Red Fort belongs as much to the Tomars, Chahamanas, and Sultanate rulers, whose work laid its structural foundations, as it does to Shah Jahan.

Conclusion

From Lal Kot’s rugged quartzite to Shah Jahan’s polished sandstone, Delhi’s great forts form an unbroken architectural lineage. The Mughal Red Fort is not an alien imposition from the steppes; it is the zenith of an indigenous fortification tradition, refined over centuries by the hands and minds of India’s own builders.

When we see the Red Fort on Independence Day, we are not just seeing Mughal Delhi. We are looking at the deep roots of India’s own architectural genius, a story that began on the rocky ridge of Mehrauli a thousand years ago and still defines the nation’s skyline today.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.