Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

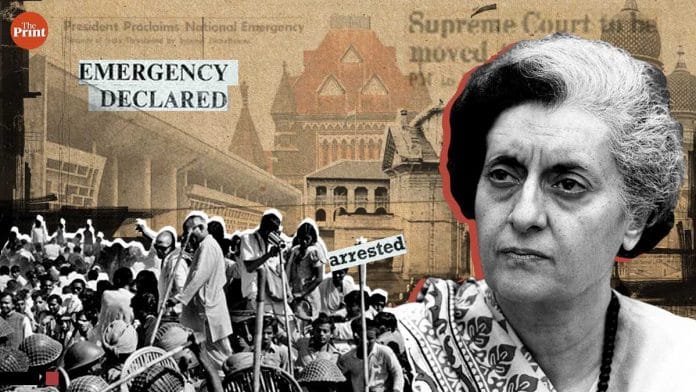

The Emergency of 1975–77 is remembered for the suppression of dissent, censorship of the press, and changes to the Constitution that concentrated power in the hands of the executive. But what followed was just as important, though less visible. India’s democracy was not restored through big speeches or sudden revolutions. It recovered slowly, through steady efforts—court rulings, new laws, citizen movements, and a growing demand for accountability.

We tend to forget that the Emergency itself was triggered by a court ruling. In 1975, the Allahabad High Court found Prime Minister Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractice and invalidated her election. Instead of accepting the verdict, the government declared a national Emergency, suspended democratic rights, and rushed through the 39th Amendment. This amendment specifically placed the Prime Minister’s election beyond the reach of judicial review, allowing her to remain in office despite the court’s ruling.

For much of independent India’s early history, constitutional battles between Parliament and the judiciary reflected genuine debates about the country’s future—land reform versus property rights, nationalization versus free enterprise, social justice versus individual liberty. Amendments were used to advance national goals, even when they overruled court judgments. But during the Emergency, constitutional power crossed a line. It was no longer about shaping India’s destiny; it was about shielding one individual from the rule of law.

The 42nd Amendment, called the “Mini-Constitution,” pushed the Emergency’s power grab even further. It placed most laws beyond judicial review, gave Parliament unchecked amending power, weakened the judiciary, tightened executive control over Parliament and the states, and tried to tilt the constitutional balance by elevating Directive Principles over Fundamental Rights. When the Emergency ended, the Janata Party swept to power and moved quickly to undo the worst excesses. The 44th Amendment reasserted the sanctity of life and liberty during emergencies, reinstated legislative term limits, and imposed stricter checks on the use of emergency powers.

In a way, the story, as the saying goes, had a happy ending. Indian democracy survived its gravest assault. When Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980 she did not attempt further constitutional overreach. Most importantly, scarred by how easily institutions had been bent during the Emergency, the judiciary emerged more assertive and determined to guard its independence, marking a significant shift in India’s constitutional journey after 1977.

Its most powerful innovation was the Basic Structure Doctrine—a remarkable idea crafted just before the Emergency, almost without parallel anywhere else in the world. While Parliament had wide powers to amend the Constitution, the Court declared that it could not alter its core principles: democracy, federalism, judicial review, secularism, and fundamental rights. For the first time, a court asserted the right to strike down even a constitutional amendment if it violated the spirit of the Constitution. This was not merely judicial activism; it was an act of democratic foresight. Though the doctrine itself evolved gradually through multiple battles between Parliament and the judiciary, by the time of the Emergency ended it stood ready as a line of defence. What began as a creative innovation matured into Indian democracy’s greatest institutional safeguard, just when it was needed most.

The other hard lesson of the Emergency was how vulnerable the courts had become when the executive controlled judicial appointments. The warning signs had appeared earlier, when in 1973, Justice A.N. Ray, who had consistently sided with the government in major constitutional battles, including dissents supporting bank nationalization, opposing the Basic Structure Doctrine, and upholding the suspension of civil liberties, was appointed Chief Justice of India, superseding three more senior judges. It sent a chilling message: judicial loyalty, not constitutional principle, would be rewarded. Determined not to be sidelined again, the judiciary gradually asserted primacy over appointments through a series of rulings, leading to the creation of the Collegium system, where judges themselves would have the decisive say in selecting and elevating judges. In most democracies, the government plays a major role in judicial appointments. India, scarred by the experience of the Emergency, chose a unique path: judges would choose judges. It was not written into the Constitution but evolved through judicial interpretation, becoming a system unlike any other.

The courts also intervened in another critical area: the political misuse of Article 356. Originally intended as a safeguard for genuine constitutional breakdowns, it had been turned during the Emergency into a tool for dismissing opposition-ruled state governments on flimsy grounds. The practice did not end with the Emergency. Successive governments across party lines continued to invoke President’s Rule for partisan advantage, undermining federalism and eroding the spirit of the Constitution. It would take nearly two decades and a decisive Supreme Court intervention in the S.R. Bommai case for clear limits to be placed on this power. For the first time, the Court asserted that President’s Rule could be reviewed by the judiciary and that the real test of a government’s majority must be inside the legislative assembly, not based on the reports of Governors. It was another quiet repair, essential to restoring balance between the Centre and the states.

Another quiet but far-reaching innovation was the rise of Public Interest Litigation, or PIL. Traditionally, access to the courts had been limited: only those directly affected by a matter could bring a case. But after the Emergency, the judiciary widened the doors. Judges began allowing citizens, activists, and even concerned individuals with no personal stake to bring issues of broader public concern before the courts. This shift transformed the judiciary from a passive arbiter into an active protector of rights. Bonded labour, environmental degradation, custodial deaths, corruption—all entered the courtroom through the mechanism of PIL. This was not just an expansion of access; it was a reinvention of the court’s role. Unlike in most democracies, where strict rules of standing kept courts away from public grievances, India created a uniquely open and activist model of justice. Here, anyone could speak for those who could not. Justice was no longer a private remedy; it became a shared public good. In allowing the invisible to be heard, India’s judiciary quietly reshaped the meaning of democracy itself.

The courts and Parliament also helped usher in another quiet revolution: the Right to Information. While many democracies had freedom of information laws, India’s RTI Act became something larger—a mass tool of empowerment, reaching far beyond journalists and activists to millions of ordinary citizens. It was not merely about transparency; it reshaped the daily relationship between citizen and state, making accountability a living expectation rather than a distant ideal.

India’s democratic recovery after the Emergency was not a clean break or a heroic restoration. It was a slow, improvised repair. Institutions were patched rather than rebuilt. Democratic spaces reopened, but the memory of strain remained. The courts adapted too, asserting new principles like the Basic Structure Doctrine and expanding access through Public Interest Litigation. It was not a sweeping revolution but a quieter process of persistence and adjustment. The republic bent, adapted, and endured. The habit of quiet repair remains an essential part of India’s democratic DNA.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.