Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

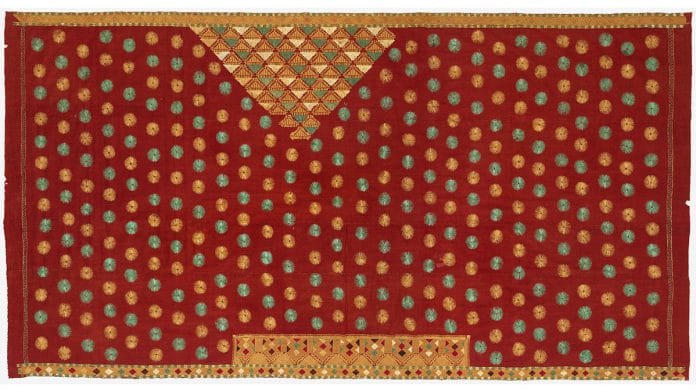

A Phulkari is more than just an art that means ‘flower work’. The fabrics, like historical documents, show and explain the social and cultural environment of their times.

The Roots and Resonance of Phulkari

The word ‘phulkari’ literally means ‘floral’ and ‘stitched work’ or ‘embroidery’. Phulkari was also woven in the name called ‘baagh’ (garden) in some of the present-day cities of Pakistan, i.e., Peshawar, Rawalpindi and Hazara. Kari means a chain, which is literally made of embroidered flowers, but it also means a strong expression of pride in Jat traditions and an expression of a longing to form stable familial relationships. Traditionally, the mothers and grandmothers of the family would sew several of these for each daughter to give as a dowry when she got married. They were part of the dowry’s bistre (bedding sets), but they were also often worn as shawls.

In India, the districts of Amritsar, Jalandhar, Ludhiana, Kapurthala, Hoshiarpur, Ferozpur, Bhatinda, and Patiala in East Punjab are considered to be the hubs for weaving the traditional art of phulkari. Although its exact origin is unknown. According to renowned scholar and ardent supporter of Phulkari S.S. Hitkari, the phulkari originated in the Khatri community of Sikhs and Hindus. Punjabi folklore and the Guru Granth Sahib both make mention of phulkari, and Guru Nanak Devji highlights embroidery as a crucial component of feminine responsibility. It was in 1882, after Maharaja Ranjit Singh approved the first export agreement for phulkaris, that commercial activity started. The oldest items that are known to exist are Phulkari shawls and handkerchiefs that were embroidered in the Chamba style in the fifteenth century by Bebe Nanaki, the sister of the first Sikh guru, Guru Nanak Dev ji. When Arjun Dev ji, the fifth Sikh Guru, married Mai Ganga, he used these items, which have been preserved in Sikh holy sites in Punjab.

The Language of Motifs and Memory

Every phulkari has a story to tell. For example, the ‘Vari Da Bagh’ is a special phulkari that a bride’s mother-in-law gives her when she moves into her new home. It represents the start of a new relationship and the continuation of tradition. The ‘Chope’, which is usually given by the bride’s maternal grandmother, and the ‘Sainchi’, which often has scenes from everyday life, are two other types. Grandmothers taught their granddaughters, mothers taught their daughters, and this way, the craft became a living link between the past and the present.

Phulkari as Domestic Art and Family Heirloom

According to the writings of Rajender Kaur and Ila Gupta, Phulkari is ‘a symbol of happiness and prosperity’ and ‘Suhag’ (marital well-being) for a married woman. In Punjabi customs, the maternal grandmothers put a lot of time, effort, and pride into embroidering ‘Chope’ Phulkari to make it a special gift for their granddaughter’s wedding. Traditional Phulkari is made of Khaddar, a type of spun cloth that was dyed and woven by hand. It uses high-quality untwisted silk thread called ‘pat’ and has bright colours like red, green, gold, yellow, blue and pink. Flora Annie Steel wrote in the Journal of Asian Art in 1888 that Phulkari was a home craft that people made for fun and for themselves or to give to loved ones. It was never meant to be sold. During colonial rule, these became part of a gift basket that people in the area called ‘dali’. These baskets were given to the British and other high-ranking officials on Christmas and as a way to show gratitude. The women used to make the traditional Phulkari of Punjab after they had finished their chores. They used to sit together in a group called ‘Trinjan’, where all the women did embroidery, dancing, laughing, gossiping, and weaving. There are not many women alive who can tell us how important these beautiful fabrics were to them.

Phulkari after Partition

The Partition of India caused millions of people to die and be forced to leave their homes, which turned out to be one of the largest migrations in history. Many refugees had to travel in terrible and dangerous conditions on trains to get to either side of the border. Some Phulkaris made it across, but others got lost and never made it. The Punjabi women’s Phulkaris had to deal with most of these dividing lines. The trade routes that brought raw materials to the craft were completely cut off; phulkari production almost stopped. Phulkaris, once treasured family heirlooms that brought back happy memories, seemed to be gone forever. The first major American exhibition of Punjabi phulkari textiles opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMOA) is one of the few in the West that talks about the chaos and disorder that the Partition caused in the lives of ordinary Indians. The exhibition includes videos that look at the political and social unrest instead of glossing over it for a Western audience. Dr. Cristin McKnight Sethi, Dr. Darielle Mason, and Dilys E. Blum are the curators who chose every part of the thoughtful and timely exhibition.

In the past, phulkaris had neat, repeating rows of wheat patterns that reminded people of the endless fields of Punjab and the steady rhythm of rural life. But one ‘Darshan Dwar Phulkari’ at the PMOA stands out because of its unique design: wheat sheaves are embroidered not only across the fabric but also on top of train cars that seem to glide through the fabric. These trains, which are full of wheat, are more than just patterns. They hold the hopes and dreams of people, the excitement of new journeys, and the promise of new beginnings. It seems like the rough, simple fabric could barely hold all the feelings that went into each stitch. It wasn’t just borders that were torn apart when Partition happened; the fabric of work, love, and shared memories was ripped apart too, leaving behind only the faint traces of what used to be. These embroidered trains show us how closely the land and its people are connected and how even the simplest threads can tell stories.

Phulkari storytelling is a strong way to relate personal experiences to history and make them more universal. It establishes profound connections between history and the present, as well as between personal experiences and shared memories. As we transition to a world that is becoming more digital, phulkari stories show us how to keep and share knowledge from one generation to the next.

References:

-

- Mooney, Nicola. “A Wedding Phulkari and Other Gifts.” In Rural Nostalgias and Transnational Dreams: Identity and Modernity Among Jat Sikhs, 207–15. University of Toronto Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442694934.12.

- Maskiell, Michelle. “Embroidering the Past: Phulkari Textiles and Gendered Work as ‘Tradition’ and ‘Heritage’ in Colonial and Contemporary Punjab.” The Journal of Asian Studies 58, no. 2 (1999): 361–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2659401.

- Sinha, Bipin K. “The Beauties of Indian Embroideries.” The American Magazine of Art 17, no. 11 (1926): 586–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23929544.

- Mooney, Nicola. “Farming, Family, and Faith: Elements of Jat Sikh Identity.” In Rural Nostalgias and Transnational Dreams: Identity and Modernity Among Jat Sikhs, 47–86. University of Toronto Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442694934.7.

- Mohamedali, Farida. “How the Partition almost killed the glorious tradition of Punjabi phulkari embroidery” Scroll.in, 2017. https://scroll.in/magazine/833579/how-the-partition-almost-killed-the-glorious-tradition-of-punjabi-phulkari-embroidery

- Siamwalla, Jamila, “When the Women of Punjab Embroidered Trains on Phulkari Cloth” Brown History, 2022. https://brownhistory.substack.com/p/when-the-women-of-punjab-embroidered

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.