Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

The Taj Mahal: When India’s Ancient Science Built an Imperial Dream

The Taj Mahal rises on the bank of the Yamuna not as a monument of romance but as a living testimony to India’s older genius in architecture and engineering. Every stone in its foundation tells a story that long predates the Mughal court that commissioned it. The techniques that hold the structure steady above a shifting river plain are the same that sustained the stepwells of Gujarat, the ghats of Varanasi, and the temples of Kanchipuram. The Mughals did not invent these ideas; they inherited them from a civilisation that had already mastered the dialogue between water, soil, and stone.

The Myth of Love and the Machinery of Power

The Taj’s reputation as a symbol of eternal love is a colonial creation. Mumtaz Mahal, Arjumand Banu Begum, died in 1631 while giving birth to her fourteenth child. Shah Jahan had other wives, and after her death he married her younger sister, Farzana Begum. The legend of singular devotion entered popular history centuries later, shaped by Victorian romanticism and British travelogues eager to sentimentalise an empire.

Abdul Hamid Lahori’s Padshahnama, the official chronicle of Shah Jahan’s reign, describes the emperor’s grief but not the poetic passion celebrated in modern retellings. The text reads like a record of power, not of love. The Taj Mahal was designed as a proclamation of imperial authority, a mausoleum that sanctified rule through grandeur. By the time E. B. Havell and other British writers saw it, the story had been rewritten, an imperial tomb rebranded as a fairy-tale romance fit for the colonial classroom.

Foundations from the River, Not the Desert

Ancient Indian treatises such as the Manasāra and Mayamata, a thousand years older than Shah Jahan, prescribed how structures near water should rest on wells filled with timber and lime to absorb moisture and vibration. Modern studies by the Central Building Research Institute confirm that beneath the Taj’s marble terrace lies exactly such a network of masonry wells. The same hydraulic principle underlies the stepwells of Rani-ki-Vav and the temple tanks of South India. This knowledge could not have originated in the deserts of Central Asia, where the Mughals’ ancestors built in clay and brick, not stone and lime.

From Samarkand to Bukhara, one finds elegant domes of glazed tiles but no marble monument rising on a river terrace. Neither the Qutub Minar nor the Red Fort nor the Taj Mahal has an ancestor in those steppes. These forms are native to Bharat’s geography, born of its temple science and perfected through centuries of experimentation with stone and water.

The Science of Light and Stone

India’s mastery of stone extended beyond quarrying. The Makrana marble used in the Taj was mined, cut, and polished by hereditary guilds from Rajasthan, families whose ancestors had carved the Jain temples of Dilwara and Mount Abu. The mirror-like sheen that dazzles visitors today comes from meena-kari polishing, recorded in Rajput workshops centuries earlier. The Mughal court provided patronage; the intellect and labour were Indian.

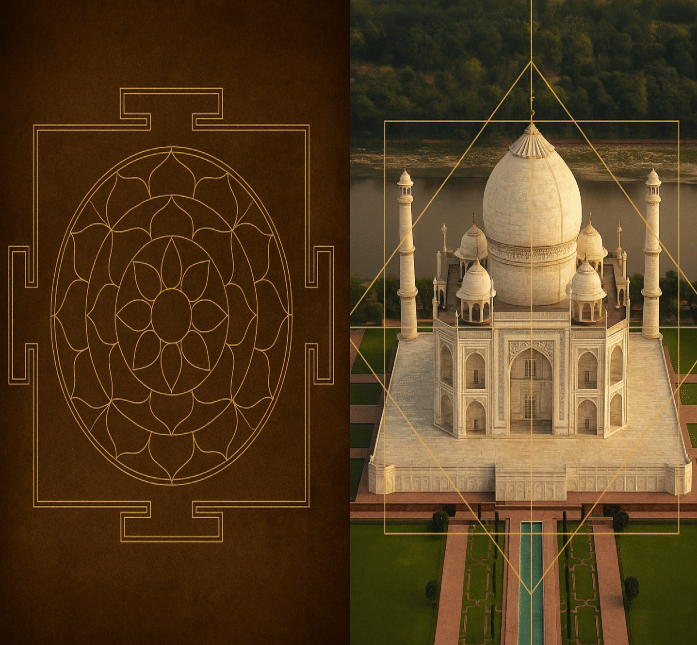

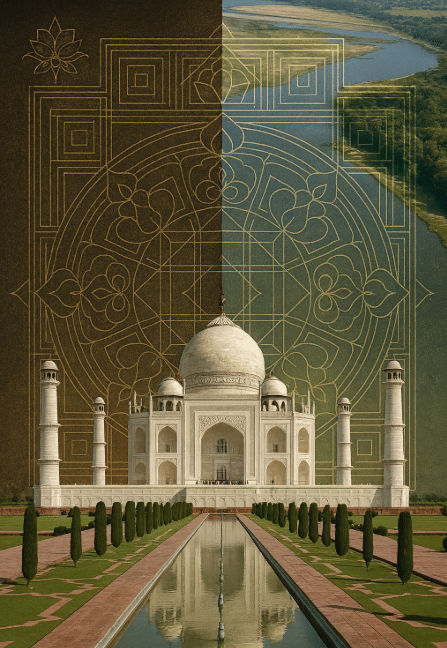

The inlay work, or pietra dura, adorning the cenotaph is likewise indigenous in design. Motifs of the lotus, bel leaf, and kalash belong to Hindu iconography, not Persian ornament. Even the so-called “Islamic” dome rests on a lotus base and follows geometric ratios found in vastu śāstra diagrams. Viewed from above, the mausoleum’s eightfold plan mirrors the aṣṭa-dala padma, the cosmic lotus pattern of temple architecture.

Hydraulic Intelligence and Sacred Geometry

The Taj’s celebrated garden, the char-bāgh, is often called Persian, yet its design follows vastu logic rather than Islamic cosmology. Its water channels intersect to form a mandala of the five elements, earth, water, fire, air, and space, just like the courtyards of South Indian temples and the tanks of palace complexes across the subcontinent.

India’s expertise in hydraulic engineering was ancient. The irrigation canals of the Guptas, the Chola tanks, and the stepwells of western India testify to a culture that understood groundwater dynamics long before the Mughals arrived. To build on the Yamuna’s shifting bank required this inherited science, wood-lined wells, lime mortar breathing chambers, and graded drainage, all features familiar to India’s temple towns.

Continuity Disguised as Novelty

When European travellers first saw the Taj, they mistook it for an “Islamic miracle in marble.” Colonial scholars later codified that assumption into the term Mughal architecture, turning continuity into conquest. Yet material evidence tells another story. The chhatris of the Red Fort, the domed pavilions of Fatehpur Sikri, and the jharokhas of Agra all evolve from the Rajput idiom that had already flowered in Mandore and Chittor. Even the pointed arch appears in India’s Buddhist chaitya caves a millennium before the Mughals.

By the seventeenth century the empire was the patron, not the originator, of an architectural system unmistakably Indian in mind and method. Its craftsmen were Hindu and Jain guildsmen; its geometry was drawn from the Śulba Sūtras; its aesthetic united symmetry with sanctity. The Mughals added poetry to the blueprint, but the blueprint was Bharat’s.

The Living Legacy

Travel today through Central Asia and you will find brick and tile but not a single monument built wholly of marble or limestone. The skill, the quarries, and the climatic need were all India’s. The Red Fort, the Qutub Minar, and the Taj Mahal could only have risen where stone was sacred, and rivers demanded respect. These are monuments not of imported genius but of a land that taught the world how to build with light, gravity, and faith.

The Taj endures because India’s science endures. Its foundations rest on ancient hydraulics; its proportions echo the mandala; its beauty flows from the crafts of those who saw no difference between art and prayer. The marble dome may commemorate an emperor, but the mind that conceived its harmony belongs to Bharat alone.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.