Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

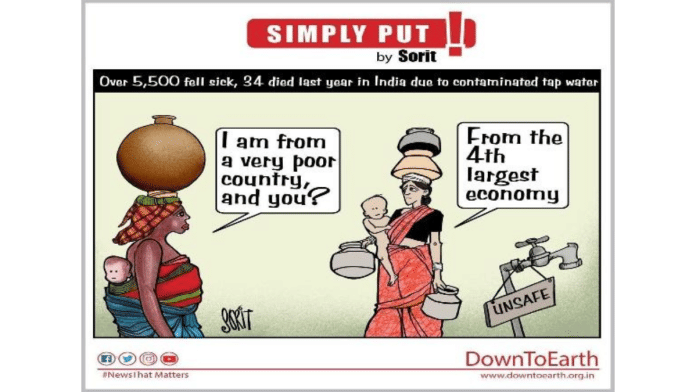

This cartoon is doing the rounds. It is disarmingly simple. Two women stand facing each other. One is African, visibly impoverished. She says, almost apologetically, “I’m from a poor country. You?” The second woman, Indian, appears even more impoverished. Her reply lands like a punch: “I come from the fourth largest economy.”

In a few lines and a single frame, the cartoon demolishes one of the most aggressively marketed myths of our time – that India’s rise as a global economic power has translated into dignity, security, and wellbeing for its people. The claim that India is now the “fourth largest economy” is paraded endlessly by political leaders, corporate media, and nationalist cheerleaders. It is spoken with pride, as though the number itself were proof of progress. Yet the cartoon asks the only question that matters: for whom?

Economic rankings are abstractions – Hunger is not!

India’s ascent in global GDP rankings has been achieved not through the elimination of poverty, but through its management – its containment, its invisibilization, and increasingly, its moral justification. When leaders boast of trillion-dollar economies, they speak a language far removed from the daily realities of the majority: stagnant wages, rising food prices, precarious employment, crumbling public health systems, and the quiet normalisation of deprivation.

According to global hunger and nutrition indices, India continues to perform worse than many poorer African nations. Child malnutrition, stunting, and anaemia remain endemic. Millions survive through informal labour with no social security, no healthcare, and no protection against sudden economic shocks. For women—especially Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, and rural women—the burdens are multiplied: unpaid care work, unsafe employment, malnutrition, and systemic exclusion.

The cartoon’s genius lies in its inversion of expectations. It forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: GDP growth does not automatically translate into human development. In fact, under neoliberal regimes, it often coincides with widening inequality. Wealth accumulates at the top, while poverty deepens below. The poor do not disappear; they are merely written out of the narrative.

India today is home to some of the world’s richest individuals—and some of the world’s poorest citizens. This coexistence is not accidental; it is structural. Tax concessions to corporations, aggressive privatisation of public assets, the weakening of labour protections, and the shrinking of welfare programmes have produced a model of growth that is spectacular for balance sheets and brutal for bodies.

To question this model is to invite accusations of being “anti-national.” Poverty, like dissent, is now treated as an embarrassment rather than a policy failure. Instead of addressing structural inequality, the state offers symbolism: renamed schemes, curated spectacles, and hyper-nationalist rhetoric. The poor are asked to take pride in economic rankings while standing in ration lines.

The African woman in the cartoon does not boast about her country’s GDP. She names her reality plainly: “I’m from a poor country.” There is honesty in that admission. The Indian woman’s response, by contrast, is soaked in irony. She belongs to a nation that claims global economic stature, yet her lived experience is one of deprivation so severe it exceeds the stereotype of poverty projected onto the Global South.

This is not an indictment of Africa; it is an indictment of Indian exceptionalism.

For decades, Indian elites have measured progress by proximity to Western capitalist standards—growth rates, investment inflows, stock market highs—while ignoring indicators of human wellbeing. Education becomes a private commodity. Healthcare becomes a privilege. Housing becomes speculative capital. Food security becomes charity. The state retreats, the market advances, and the poor are told to be grateful.

What the cartoon exposes is the violence of this economic imagination. It asks whether a nation can call itself successful when its women are hungry, its children malnourished, and its workers disposable. It challenges the moral emptiness of celebrating economic size without economic justice.

The phrase “fourth largest economy” has become a slogan, not a solution. It functions as a shield against accountability. Any criticism of inequality is dismissed as negativity. Any demand for redistribution is labelled populism. Meanwhile, public wealth is steadily transferred into private hands, and poverty is reframed as a personal failure rather than a political choice.

True development is not measured by how high an economy ranks, but by how low its levels of hunger, homelessness, and despair fall. It is measured by whether women can eat adequately, whether children can learn without hunger, whether workers can live without fear of sudden ruin.

The cartoon leaves us with a haunting image: an Indian woman poorer than her African counterpart, standing beneath the weight of an economy that claims greatness while denying dignity. It is a reminder that numbers do not feed people. Justice does.

Until India confronts this contradiction—until it chooses redistribution over spectacle, welfare over vanity, and people over profits—the claim of being a “top global economy” will ring hollow. The world may applaud the ranking. The poor will continue to bear the cost.

And that, finally, is the truth the cartoon refuses to let us ignore.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.