Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

Part I

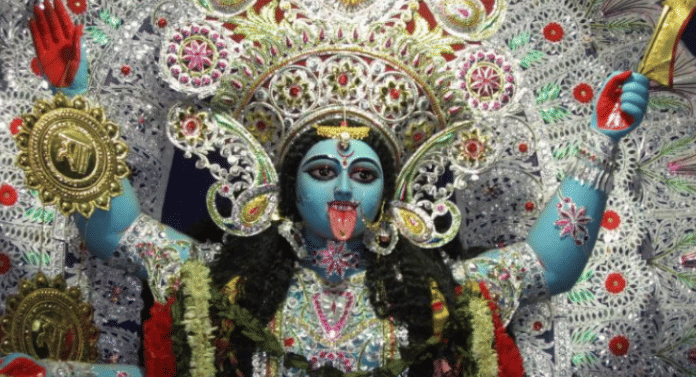

Autumn heralds the festivities of the mother goddesses, and in Bengal, Kali’s presence resonates deeply, particularly during Kali Pujo. Kali transcends the realm of a mere deity, embodying a potent force that weaves contrasting attributes – nurturing love and an unyielding might. This paradox lies at the heart of Kali’s appeal, reflecting the intricate balance of the universe and the eternal cycle of creation and destruction. The discovery of terracotta figurines at excavation sites across the subcontinent underscores the ancient roots of mother goddess reverence, highlighting a long-standing cultural significance. These artifacts suggest connection to fertility cults celebrating the cycles of nature and agricultural abundance. D.D. Kosambi, H.D. Sankalia and others have fascinatingly observed the intimate links between these ritualistic performances concerning the mother goddess images in the early agricultural societies. However, Kali’s evolution as a mother goddess is complex and multifaceted. Her depiction as a fearsome figure standing on Shiva’s chest, juxtaposed with her maternal role, invites diverse interpretations. Some see her as embodying Shakti, the feminine energy that transcends traditional power structures, redefining the balance between masculine and feminine principles (Purusha-Prakriti). Others view this imagery as a symbolic reversal of patriarchal norms, highlighting the intricate dynamics of her divine representation.

The worship of Kali as a primordial feminine force was deeply rooted in the indigenous communities. Wendy Doniger suggests Kali’s origins can be traced to the deities of the Pre-Vedic village, tribal, and mountain cultures of South Asia, who were gradually appropriated and transformed by the Sanskritic traditions. Although the word Kali appears as early as the Atharva Veda, the first reference to Kali comes from Kathaka Grihya Sutra where the goddess is mentioned as Bhadra Kali along with the other Vedic deities. Kali’s depiction as a non-pacifying goddess is echoed in the Mundaka Upanishad where she is referred as one of seven flickering tongues of the Vedic God, Agni. Thomas B. Coburn enlightens on a more predominant account of the goddess as the wild, bloodthirsty, and frightening power that appears in the Sauptika Parvan of the Mahabharata, during Asvatthama’s night attack on the Pandavas. Subsequently, in the early medieval Puranas, Kali emerges as a goddess of battle and war, often associated with distinct population groups living beyond the settled mainstream cultures. However, her most famous manifestation is found in the ‘Devi Mahatmya’ section of the Markandeya Purana, where she appears as a wrathful projection of Durga. Emerging from Durga’s frowning brow, Kali embodies destruction: sword in hand, garlanded with skulls, clad in tiger skin, with a haunting presence. Her emaciated form, gaping mouth, and grotesquely outstretched tongue evoke terror. With fierce determination, she battles the asuras, notably Raktabeeja, devouring his blood to prevent replication, and in this battle, she assumes the formidable form of Chamunda – bloodthirsty, hideous, and withered – raging across the battlefield to slay the demons Chanda and Munda. This depiction as observed by Dhrubakumar Mukhopadhyay in his edited volume on the Shakta Padabali, is also mentioned in the Brihaddharma Purana, written around thirteenth century. In the contemporary and subsequent Puranic literature, Kali’s character evolves beyond personification, emphasizing her fierceness as a combined force – a wild, untamed power associated with cemeteries and wild forests. Her name, linked to darkness, underscores her role in the cyclical nature of time (Kala), where death paves the way for new beginnings, also symbolizing the destruction of ego, a necessary step toward liberation.

Though Kali’s presence was noted in the Puranic literature, it was Krishnananda Agamabagish, a revered Shakta scholar from Nadia, who popularized her worship among the masses. Krishnananda Agamabagish is believed to have lived in the 16th-17th century CE and is attributed to the first worship of the goddess within the domestic confines. Prior to his efforts, Kali worship was largely confined to Tantric practitioners involving rituals to be met with stone icons or the clay ghatas along the river banks and in the uncharted territories of the deep forests. Agamabagish is said to have received a divine vision of the goddess in a dream, who instructed him to model her after the first person he encountered the next morning. In the early dawn, Agamabagish met a woman along the bank of the Ganges. She was of an indigenous origin, possibly a Gopbadhu or Bagdibodhu, with a rich earthy tone, dishevelled hair with a partially draped saree. She was working on the cow dungs. Krishnananda was struck by her image, particularly when she put her tongue out in a gesture of shame, seeing him. Krishnananda’s vision led to the creation of the iconic form of Kali, popularizing her domestic worship and establishing the tradition of autumnal worship during Kartika Amavasya.

To be continued in Part II

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.