Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

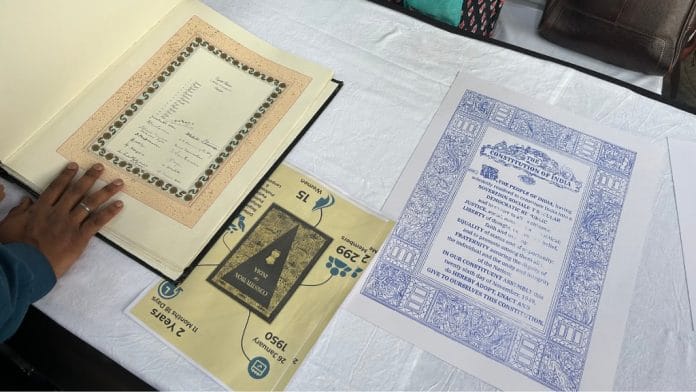

India’s Constitution did not envisage Chief Ministers standing at the gates of law enforcement, arms folded, declaring no entry. Yet that is the spectacle now unfolding in West Bengal, where a State government appears determined to test how far political power can stretch before the rule of law snaps.

This is being sold, predictably, as a battle for federalism. It is nothing of the sort.

Federalism is a system of distributed authority, not a licence for selective obedience. It does not allow States to veto parliamentary law, obstruct criminal investigations, or physically impede officers acting under Central statutes. When that line is crossed, what remains is not autonomy but nullification—the deliberate disabling of the Constitution by executive will.

Let us be clear. India is a Union of States, not a loose confederation of political satrapies. Criminal law is a Concurrent subject. Money laundering is a Central offence. Laws enacted by Parliament are binding across the Republic. A State’s control over “law and order” does not extend to shutting down investigations it finds inconvenient. The Constitution is not an à la carte menu.

The claim that Central agencies require State permission to function is a half-truth elevated to a political doctrine. Once a matter is before the Supreme Court, State consent becomes irrelevant. Court directions are not suggestions. They are commands—backed by contempt powers that attach personally, not abstractly.

Which brings us to the most uncomfortable truth Indian politics prefers to avoid.

A Chief Minister enjoys no constitutional immunity.

None.

Not from investigation.

Not from questioning.

Not from arrest.

High office is not a force field. It is a position of trust, not a sanctuary. Courts insist—correctly—on restraint when dealing with elected executives. But restraint is conditional on cooperation with law. When cooperation ends, restraint has no constitutional mandate.

The danger here is not the arrest of one individual. It is the precedent being manufactured: that electoral mandate can be deployed as a shield against statutory authority. That votes convert executive power into personal impunity. That a government, once elected, can decide which laws apply and which must wait outside the gates.

This is how democracies rot—not with tanks, but with applause.

What we are witnessing is the creeping normalisation of mob-enabled governance. When party cadres, sympathetic police forces, and orchestrated outrage are used to physically block lawful investigation, the State ceases to be a neutral enforcer of law and becomes a participant in its obstruction. Democracy slips into something uglier: rule by intimidation, draped in populist language.

Much noise is now being made about President’s Rule, as though it were an impatient Centre’s favourite weapon. This is a convenient distraction. The real constitutional fault line lies elsewhere—in Article 256, which obliges States to ensure compliance with parliamentary law. When a State openly defies that duty, it is not exercising autonomy. It is announcing rebellion against constitutional order.

President’s Rule is not imposed because the Centre dislikes a State government. It is imposed when the Constitution is rendered unworkable. And courts, post-Bommai, will rightly scrutinise any such move with hawk-eyed suspicion. But scrutiny cuts both ways. Persistent, wilful obstruction of Central law is not federal assertion; it is constitutional sabotage.

The Supreme Court now confronts a moment that transcends West Bengal.

It must answer questions that will define the Republic’s trajectory:

Can States weaponise federalism to shield alleged criminality?

Can elected power overpower the rule of law?

Can the Union’s laws be treated as optional, depending on political alignment?

If the answer to any of these is yes, then the consequences will not stop at one State. Tomorrow, every Chief Minister will claim the right to declare investigative “no-go zones.” The day after, court orders will be negotiated on the streets. At that point, India will still fly one flag—but live under many laws.

A Republic cannot survive on street vetoes.

Democracy does not mean immunity.

Federalism was designed as a balance—not a bunker.

The Kicker

If Chief Ministers can decide which laws enter their States and which stay outside the gates, then the Constitution is no longer the supreme law of the land. It becomes a polite suggestion—honoured when convenient, ignored when threatening. And when law begins knocking and politics bolts the door, what follows is not resistance. It is abdication. Of duty. Of oath. Of the Republic itself.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.