Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

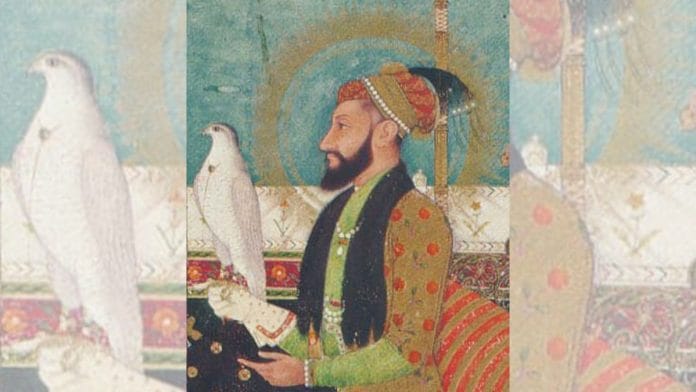

From the early sixteenth century, the Mughal Empire’s Tirth Yatra Mehsul—a special levy on Hindu pilgrims—transformed sacred journeys into weapons of subjugation. It formed part of a broader policy under emperors such as Aurangzeb, alongside the reinstated Jizya and temple destructions, that sought to marginalise non-Muslim subjects and assert imperial dominance.

For countless pilgrims, often already living hand-to-mouth, the Mehsul proved ruinous. A journey to venerable shrines such as Varanasi and Gaya now carried an additional burden that swallowed any savings set aside for offerings or sustenance. Families scrimped on essentials, borrowed at exorbitant interest, and sometimes abandoned their plans altogether when the combined cost of travel, lodging and tax outstripped their meagre means. In effect, the Mughal state weaponised poverty to sever Hindus from their spiritual heritage.

The economic fallout rippled through entire communities. Towns reliant on seasonal pilgrimage trade—supplying flowers, sweets and votive souvenirs—experienced deserted ghats and shuttered markets. Merchants who once thrived on devotees’ patronage lamented the collapse of commerce, while temple treasuries dwindled. The Mehsul thus became a double-edged sword, extracting fiscal tribute and inflicting communal impoverishment in one stroke.

Yet the Mehsul did more than drain pockets: it struck at social cohesion and religious liberty. The Upanishads exalt the pilgrimage toward moksha as sacrosanct, and the Kathā Upanishad insists on the necessity of penance and travel for spiritual progress. By taxing these very rites, Mughal authorities flagrantly violated the principle of ahimsa (non-violence) and sent a clear message that traditional rites no longer enjoyed state protection.

Resistance quickly sprang up at temple steps and village squares. Elders and temple committees petitioned local governors for relief only to face brutal reprisals—fines, imprisonment and public flogging. Contemporary chronicles recount cavalry patrols dispersing peaceful assemblies, with dissenters bound and beaten. Such encounters revealed the regime’s readiness to crush both fiscal and political opposition, equating tax defiance with sedition.

Faced with relentless pressure, Hindu communities adapted in remarkable ways. Dharamshalas (charitable rest-houses) and langars (community kitchens) sprang up along pilgrimage routes, funded by local philanthropists and temple trusts. These institutions provided free lodging and meals, easing the financial burden on the poorest devotees and preserving the flow of pilgrims against all odds.

Some travellers evaded the Mehsul by choosing lesser-known shrines or circuitous paths outside official revenue records. These “hidden” yatras fostered new centres of worship—clandestine enclaves where the flame of devotion burned bright despite imperial bans. In doing so, they enriched India’s religious geography and demonstrated that faith can flourish even when driven underground.

Patronage also played a vital role. Maharajas, zamindars and wealthy merchants, recognising the social and spiritual capital of pilgrimage, sponsored entire processions. They paid the Mehsul on behalf of villagers, turning private wealth into a shield against oppression and rallying communities around a common cause. Their largesse embodied the dharma of solidarity, reminding the emperor that collective devotion is not so easily extinguished.

Under Emperor Akbar, a brief thaw in religious policy saw certain non-Muslim taxes relaxed, and the pilgrimage levy partially reduced. This interlude underscored the potential for advocacy and negotiation even under a regime often characterised by intolerance. Yet the reprieve proved fragile as later rulers reinstated harsher measures. By the mid-eighteenth century, as Mughal authority waned, the Mehsul faded into obscurity, only to endure in collective memory as a cautionary tale of fiscal tyranny.

Today, historians regard the Tirth Yatra Mehsul not merely as an anachronistic levy but as a warning: when a state taxes conscience and devotion, it risks igniting a deeper resistance grounded in spiritual conviction. Pilgrims who traversed deserts or mountains to reach the divine refused to be counted by coin. Their footsteps, echoing along ancient trails, remind modern India that religious freedom was secured not by complacency but by courage—by those who chose the path of dharma despite sword and scourge.

Professor and Head, Department of English; Principal (OSD), Baroda Sanskrit Mahavidyalaya;

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

Mobile: 09558805745 | Email: hitesh.raviya-eng@msubaroda.ac.in

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.