Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

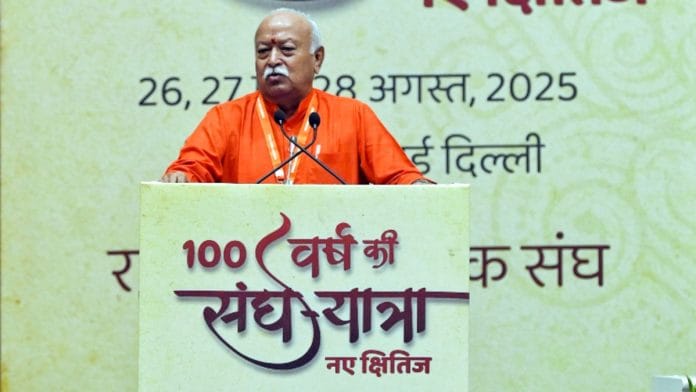

Last week’s centenary celebration appeared to be a major effort by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) to reach out to a broader audience beyond its usual ideological base. A key aspect of this outreach was a careful elaboration of how the organization uses and conceives the word ‘Hindu’.

Throughout the three-day event, Dr. Mohan Bhagwat, the current chief of the RSS, emphasized that the word does not refer to followers of a single faith. As used by the RSS, ‘Hindu’ includes Indian Muslims and Christians, among others. “Hindu means inclusive,” Bhagwat remarked, “and there is no limit to inclusivity.”

As an academic philosopher interested in language, I was particularly drawn to the distinction Bhagwat made between ‘meaning’ (he used the word bhāvārtha) and ‘content’ in his explanation of ‘Hindu’. While acknowledging that cognates like Bharatiya, Hindavi, and Indic are synonyms (i.e., they share the same meaning), Bhagwat argued that they lack the content of ‘Hindu’. This, he claimed, is why the Sangh insists on using the term.

Bhagwat’s discussion of the etymology of ‘Hindu’ suggests that he intends the meaning of the word to be determined geographically: ‘Hindu’ is derived from a word that the ancient Persians used to refer to the inhabitants of the region west of the Indus. However, Bhagwat explained that the content of ‘Hindu’ is wider and includes elements like devotion towards the Indian motherland, an ancestral tradition, and a common genetic makeup.

In discussions within semantics — the branch of linguistics and philosophy concerned with meaning — there is no established or commonly accepted definition of ‘meaning’ and ‘content’, nor is there an agreement on how the distinction between them must be drawn. Semanticists use precise definitions for the distinct concepts that these words are used to refer to. It was thus tempting for me to try to understand the import of Bhagwat’s claim using what we know about language in more academic discussions, and assess if his message of inclusivity would survive such translation.

The Navya Nyaya philosophers of medieval India — who had an obsession with distinguishing different kinds of meaning — distinguished Vācyārtha from tātparyārtha. Vācyārtha is the primary, literal meaning of a word (e.g., ‘New Delhi’ refers to the capital of India) while tātparyārtha is the intended meaning (e.g., when a fruit vendor says ‘bananas’, they intend to sell them but when a child says the word, they want a banana to eat). Perhaps Bhagwat’s use of ‘meaning’ (or bhāvārtha) corresponds to Vācyārtha while ‘content’ corresponds to ‘tātparyārtha’.

However, this is likely to be counterproductive. If the aim of the RSS’s centenary celebration was to reach out to a wider group that is not already convinced of the pluralistic ambitions of the Sangh, its intentions behind insisting on using ‘Hindu’ are likely to be treated with suspicion. This is so particularly because of some divisive definitions of the term proposed by some ideological pillars of the Sangh in the past, including V.D. Savarkar.

The distinction between ‘meaning’ and ‘content’ may remind one of the distinction between ‘reference’ and ‘sense’ introduced by the 19th century German philosopher Gottlob Frege. The reference of a word is the set of things that a word refers to. ‘University’ refers to all Universities. The sense of a word, however, is a condition associated with a word that determines the reference. The referent is whatever satisfies the sense e.g., sense of ‘University’ can be conditions like ‘an institution for higher learning and research’, ‘an organization that awards academic degrees’, etc.

But Bhagwat could not have had this distinction in mind. Several people — including myself — carry a devotion towards the Indian motherland and have the common genetic makeup (which Bhagwat claims goes back 40,000 years) but live east of the Indus. If ‘content’ is sense, then the content of ‘Hindu’ will classify such people as Hindus. But this is incongruent with the reference of ‘Hindu’, which on Bhagwat’s construal, includes people living west of Indus. (Whether Bhagwat is right about the geographically determined reference of ‘Hindu’ is a separate challenge.)

Perhaps the distinction between ‘meaning’ and ‘content’ corresponds to another of Frege’s distinction between reference and ‘ideas’. Ideas include subjective, potentially emotive information associated with words, which do not play any role in determining the referent. Treating ‘content’ as ideas would resolve the incongruence: the reference of ‘Hindu’ may be geographically determined, but the ‘content’ or ideas associated with ‘Hindu’ are the subjective impressions about genetics, culture, or provenance that Bhagwat lists in his speech.

However, Ideas are subjective. And the ideas associated by several people with ‘Hindu’ do not carry message of unity, particularly because of the history of the misuse of the term. The vision of serving a ‘Bharatiya Rashtra’ inspires more confidence than serving a ‘Hindu Rashtra’.

Nikhil Mahant is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow at the Department of Philosophy at Uppsala University in Sweden.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.