Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

Bombay’s rise as India’s leading commercial and financial city is often credited to cotton, geography, or British liberal trade policy, but none fully explain its transformation. Cotton became central only in the mid-nineteenth century, long after Bombay had accumulated capital, shipping capacity, and financial institutions, while geography alone cannot account for why a city with a deep natural harbour remained marginal for decades. For much of the eighteenth century, Bombay lacked a hinterland, relied on subsidies from Calcutta and Madras, and was even dismissed in 1788 by Lord Cornwallis as fit only to be a “small factory”. Hemmed in by the Sahyadri range and Maratha power, Bombay’s decisive breakthrough came not from cotton or free trade, but from opium—specifically the Malwa opium trade that Indian merchants turned into an engine of capital accumulation.

Bihar’s Opium Monopoly Set Off a Malwa Opium Surge

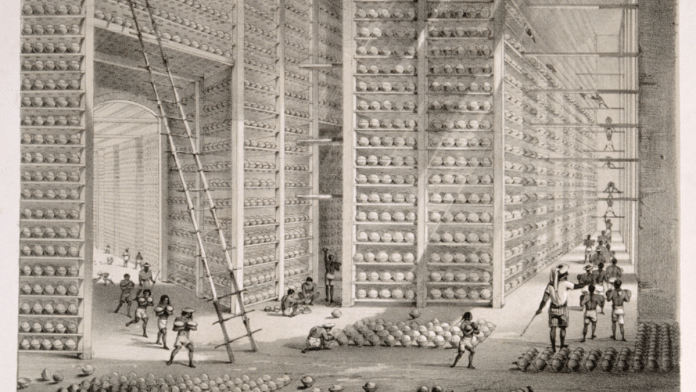

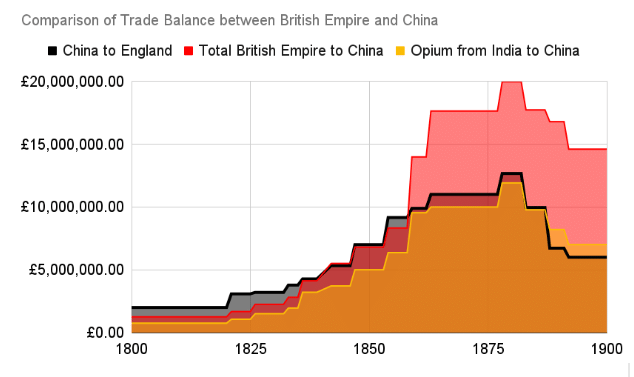

The British learned from the Portuguese how opium could be used to offset their growing trade deficit with China. The East India Company dismantled existing competitive opium markets in Bihar and imposed a strict monopoly. Cultivators were forced to grow poppy and sell exclusively to Company agents at fixed prices. The profits were enormous. By the nineteenth century, the British were selling opium at nearly four times the production cost. Opium revenues funded a substantial share of the Company’s administration and military expenses and supplied the silver needed to pay for Britain’s tea imports from China. Bihar’s opium thus became a fiscal pillar of the empire.

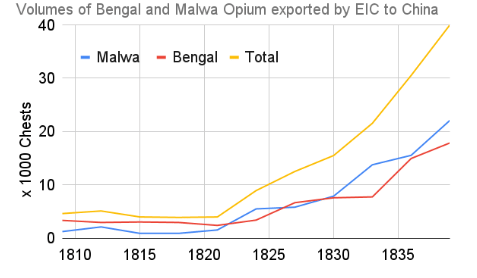

The spectacular profitability of Company opium revealed that opium wasn’t just another crop but a global trading currency. This realisation triggered a parallel development in western India. In the Malwa plateau—covering parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan—poppy cultivation expanded rapidly. Malwa lay outside direct Company revenue administration, and the British lacked the political and bureaucratic capacity to impose a Bihar-style monopoly.

How Malwa Opium Beat the Monopoly and Opened Bombay

For the East India Company, Malwa opium was a serious threat. It undercut prices at the Calcutta auctions and weakened the Company’s most profitable monopoly. British attempts to suppress the trade—through treaties with princely states, route blockades, and outright bans—largely failed [2]. Indian merchants adapted by redirecting shipments through Portuguese ports like Daman and Diu, or by sending opium across the Thar Desert to Sindh. Unable to control this trade, the Company eventually abandoned prohibition in 1830–31 and legalised Malwa opium exports through Bombay in exchange for customs duties.

This decision proved transformative. Once Malwa opium was funneled through Bombay, the city rapidly displaced older ports and became the principal western gateway for the China trade. Unlike Bengal opium, which enriched the colonial state, Malwa opium enriched Indian merchants. Parsis, Gujaratis, Marwaris, and Baghdadi Jews controlled procurement, finance, and shipping, operating in partnership with—but not subordinate to—British firms. This trade generated unprecedented profits in indigenous hands and marked a decisive moment of capital formation in western India.

How Opium Built Bombay’s Indigenous Business Class

Several of Bombay’s most prominent business families trace their early fortunes to this opium economy. Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy and the Sassoons built vast trading empires exporting Malwa opium to China. Parsi merchants and shipbuilders accumulated wealth through opium shipping, while Marwari financiers funded cultivation and inland trade. These merchant houses reinvested profits into institutions that structured modern commerce: the Bombay Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1836 to coordinate trade and lobby the state; the Bank of Bombay followed in 1840 to finance large-scale transactions and bills of exchange; the Bombay Insurance Company was established in 1839 to underwrite maritime risk; and Indo-British agency houses expanded banking and credit operations through the 1840s and 1850s. Financial coordination deepened further with the emergence of organised securities trading, culminating in the establishment of the Bombay Stock Exchange in 1875. In parallel, opium profits funded the city’s physical infrastructure—private docks such as Sassoon Dock (1875), harbour modernisation under the Bombay Port Trust (1873), expanding shipping fleets, and rail links connecting the interior to the port. Together, these institutions and infrastructures transformed Bombay into a city capable of sustaining high-volume global trade.

Bombay’s rise as India’s financial capital was thus not simply the outcome of imperial design, but of indigenous merchants converting opium-derived surplus into durable economic institutions and an enduring urban economy.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.