Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

Donald Trump marked one year of his second term in office recently. Thanks to his penchant for attention, the year felt unusually compressed with every week offering a new geo-political shock. From announcement of Tariffs on closest allies to the brazen kidnapping of the Venezuelan president to his manoeuvres over Greenland recently, the administration exceeded even the most sensational expectations.

Two broad takeaways stand out from this first year.

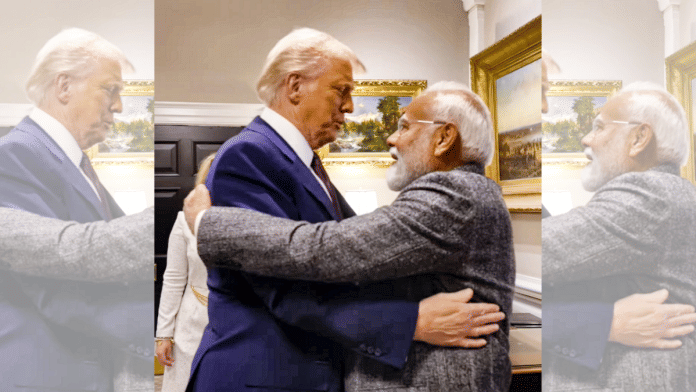

First: the unravelling of the US–India bonhomie, at least for now. No middle-class child growing up in India in the 1980s and 1990s would have expected the United States to behave so brazenly and, at times, seemingly unhinged in its foreign policy. Having experienced nearly two centuries of British rule, Indians inherit a natural scepticism toward Western powers. However the United States in many ways was cast as an antithesis to the old European order. Many believed, not without reason, that American pressure after the World wars helped accelerate decolonisation.

For those who benefitted from India’s opening up its Markets and the Globalised era that followed, the US represented a champion of the liberal order. As Americans proudly proclaim, the world’s first democracy came to be seen as a beacon of robust governance that prized liberal values like freedom and independence for all. For a generation that witnessed the internet’s birth and the benefits of a US-led global economy, the American model embodied free trade, multiculturalism and opportunity.

That optimism created a blind spot. After all, older generations vividly recall how the US tried to humiliate India during the 1971 Bangladesh crisis, or how the US (& British) support for Pakistan after 1947 pushed India into Russia’s embrace. Yet the post-2000 convergence against the rise of China, plus the effects of globalisation fostered a comfortable belief that India and the US were natural allies – a partnership too solid to break. It was easy to dismiss any voices cautioning against this overly simplistic view of geopolitics.

That complacency has been shaken. Trump Tariffs on Indian exports and persistent public rebukes over India’s purchase of Russian oil have dented this partnership in public’s eyes. If Washington’s aim was to publicly pressure New Delhi into accepting its trade terms, it misread India’s domestic politics where being seen as weak in dealing with Western powers is an electoral suicide. Add to this the undercurrent of anti-Indian sentiment in MAGA circles and inflammatory Republican rhetoric on H-1B visas, many Indians feel alienated. The result is a more sober realisation that international relations are driven by interests, not morality. America’s immediate priority of containing China explains much of its behaviour and this understanding of realpolitik shatters illusions about a supposedly unbreakable friendship. Millennials who once celebrated the US-India romance are now rediscovering the rationale behind Nehru’s non-alignment policy. However imperfect, the policy was still useful because it allowed Indian governments some space to pursue national interest without capitulating to foreign pressure.

The second takeaway of the last one year concerns the extraordinary power vested in the US presidency – a structural feature of the American constitution with global repercussions. Whatever one’s ideology, the past year underscores how much authority rests with a single individual. That concentration of power can be decisive in wartime or emergencies, but in peacetime it can produce far-reaching and unintended consequences, especially under a president determined to make his mark on history one way or another.

The constitutional checks and balances exist, yet they often feel like they are playing catch-up. A president’s ability to veto or stall legislation is especially worrying in an era of extreme polarisation. Unlike a parliamentary system where a leader can lose office quickly if they lose support of the parliament, the American president serves a fixed four-year term that is hard to interrupt. If a president is determined to reshape history, there are few immediate brakes beyond the legislature and the courts, which act after the fact. This setup reflects the founding fathers’ faith in institutions and in the electorate’s judgment while choosing the candidate for the top job. But when those institutions are tested by an assertive executive, the concentration of power can expose vulnerabilities in the world’s most powerful democracy.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.