Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

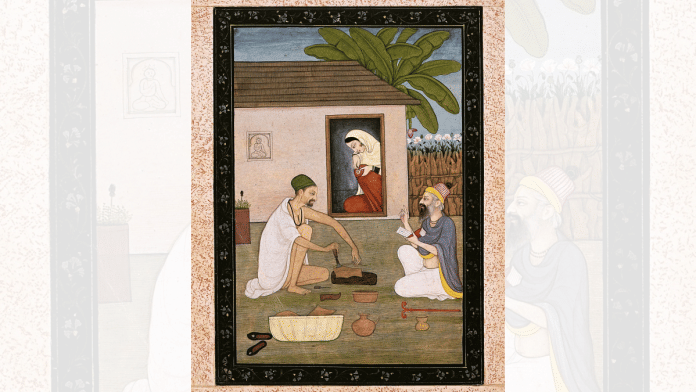

The month of February holds historical significance, particularly for those engaged in the struggle for social justice, equality, and human liberation, and who envision a society free from exploitation. Every year, on February 12, the birth anniversary of Sant Guru Ravidas is celebrated, marking his role as a revolutionary figure in India’s socio-cultural landscape. Sant Ravidas was not confined to mere devotion to God; rather, his consciousness resonated with a distinct rebellion against social injustice, caste discrimination, and systemic exploitation. It is no coincidence that within this broader movement, divergent streams emerged some of which challenged the existing social order.

Traditionally, the Indian intellectual tradition has not emphasized rigid classification of ideas. Instead, it has fostered a philosophy of coexistence rather than confrontation. However, when it comes to social structures and power relations, it becomes evident that oppressors and the oppressed cannot be placed within the same framework. Thus, presenting the Bhakti movement as a monolithic and homogenous phenomenon is not only historically inaccurate but also unjust. The hegemonic scholars of Hindi literature have deliberately attempted to depoliticize and neutralize its revolutionary potential by labeling it as a mere Bhakti movement. In reality, what they define as the Bhakti movement was far from a singular ideological entity; rather, it comprised two conflicting streams one that upheld religious devotion and submission to divine authority, and another that sought radical social transformation.

On one hand, poets such as Tulsidas, Mirabai, and Surdas emphasized devotion rooted in religious faith and surrender to God. Tulsidas’s conceptualization of ‘Ram Rajya’ (the ideal kingdom of Lord Ram) sought to preserve the traditional social hierarchy, reinforcing the varnashrama system based on religious legitimacy. On the other hand, Sant Ravidas, Kabir, Dadu, and other Nirgun saints articulated a vision that was not merely religious but deeply intertwined with socio-political transformation. Sant Ravidas’s idea of ‘Begumpura’ envisioned a society devoid of kings and beggars, free from caste and social discrimination. This was not just a mystical or spiritual aspiration it was an unambiguous call for social liberation.

A stark contrast can be observed between the ideological foundations of Tulsidas and Ravidas. While Tulsidas upheld the supremacy of a “worthless Brahmin” over a “learned Shudra” and propagated a philosophy of contentment through begging, Ravidas, in contrast, emphasized the dignity of labor and advocated for the reverence of even a “knowledgeable Chandal” (outcaste). Thus, equating Tulsidas and Ravidas within the same ideological framework is as erroneous as juxtaposing Karl Marx and Adam Smith as proponents of the same economic philosophy.

Tulsidas’s Ram Rajya reinforces the varnashrama system, whereas Ravidas’s Begumpura envisions a casteless, egalitarian society. This inherent conflict has been strategically obscured within the broader Bhakti movement. Hindi literary scholars have homogenized this discourse, concealing the fundamental contradictions embedded within it. Their agenda was to pacify this movement by categorizing it under Bhakti, thereby stifling its revolutionary spirit and preventing its potential to ignite social transformation.

To fully comprehend the dialectics of the Bhakti movement, one must also analyze the class structure of Indian society. In social theory, dialectics refers to the presence of contradictions within any ideological or social movement. The Bhakti movement was no exception. If reduced solely to God-worship and devotion, a crucial aspect its demand for social change remains obscured. Therefore, categorizing it into multiple streams is essential.

The internal conflict within the so-called Bhakti movement is evident. Figures like Mirabai, Tulsidas, and Surdas advocated individual salvation through divine grace. However, Sant Ravidas, Kabir, Dadu, and other saints did not limit their ideas to spiritual teachings; they directly challenged caste-based oppression and social injustice. Their words were not mere religious maxims but explicit critiques of the caste-ridden society. Sant Ravidas’s vision of ‘Begumpura’ was not an abstract, utopian city but an articulation of a casteless, classless, and exploitation-free society.

If this movement is solely interpreted as a Bhakti movement, it weakens its foundational radical consciousness. Hence, it must be re-examined as a Mukti (liberation) movement to restore and amplify its revolutionary potential. The relevance of this discourse persists today, just as it did in the medieval period. The struggle against caste-based exploitation, social injustice, and economic disparity continues.

Broadly speaking, two opposing streams can be identified within this movement one that sought to preserve the status quo and another that pushed for socio-political revolution. Recognizing this dialectical tension is crucial for an accurate historical and ideological analysis. The conflict between the Bhakti and Mukti movements is not just a relic of history; it remains a contemporary issue. The ideological essence of the movements led by Sant Ravidas, Kabir, and others still resonates in today’s social justice struggles.

Thus, it is imperative to reframe this discourse, to dissociate the Mukti movement from its Bhakti label, and to recognize it as an independent movement for liberation. This is essential for the oppressed sections of society to reclaim their historical legacy of resistance and transformation. The history of this movement is not merely a chronicle of religious devotion; it is also a history of socio-political struggle. A renewed scholarly engagement with this history is necessary to revitalize its radical energy and to establish it as a movement of liberation rather than passive devotion. This is the true legacy of Sant Ravidas and other revolutionary saints a legacy that has been deliberately blurred under the name of Bhakti. The time has come to critically engage with and redefine this movement in its true essence.

(The author Amit Kumar Yadav is a Research Scholar in Political Science at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi)

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint