The partition of India in 1947 triggered history’s largest forced migration, displacing 15-18 million people and claiming up to 2 million lives.

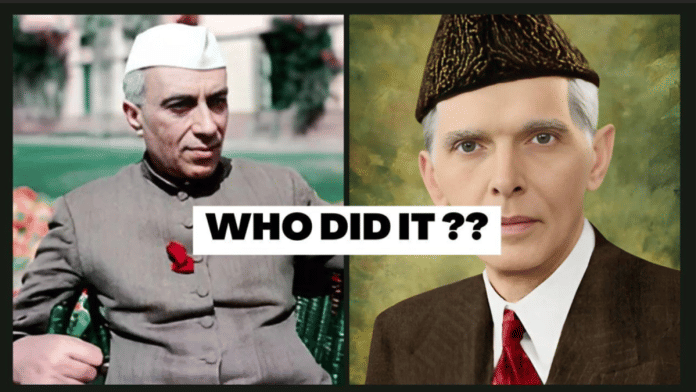

Looking beyond Jinnah and Nehru’s roles reveals a complex narrative. Cyril Radcliffe, who had never visited India, drew hasty borders while the British Parliament’s rushed Independence Act of July 1947 suggested hidden motives behind the split.

Multiple forces shaped this momentous change. The British “divide and rule” policy intensified Hindu-Muslim tensions, while strategic interests and political calculations drove this historic decision.

Was It A Strategic Interests

Post-World War II, Britain faced a crucial challenge: maintaining influence in South Asia while preventing Soviet expansion. The Indian Army, with 2.5 million volunteers, was too valuable an asset to lose completely.

Britain strategically created Pakistan as a buffer against Soviet influence, particularly important as the USSR expanded into Eastern Europe. Through 145 overseas installations across 42 countries, British military maintained regional influence.

The partition’s military impact was significant. Field Marshal Auchinleck divided the British Indian Army between the two dominions. Pakistan’s military maintained strong British ties, with 500 British officers joining their ranks. General Gracey’s appointment as Pakistan’s Commander-in-Chief in 1948 further cemented this relationship.

Britain’s strategic planning extended to Afghanistan, supporting its formation in 1919 as a buffer against Soviet influence. While the USSR quickly recognized Afghanistan in 1921, the US delayed until 1934, highlighting regional power dynamics.

The partition advanced Britain’s Cold War goals. Pakistan’s membership in SEATO (1954) and CENTO (1955) aligned with Britain’s Soviet containment strategy. Despite India’s non-aligned stance complicating regional politics, Britain maintained workable relations with both nations.

These strategic moves secured Britain’s South Asian influence through military cooperation and alliances. Pakistan’s creation served Britain’s broader post-colonial geopolitical interests.

Intelligence Operations Shaping the Partition

British intelligence agencies influenced India’s partition through covert activities. MI5’s operations included imperial counter-intelligence, working with local agencies to monitor nationalist movements.

The Intelligence Bureau (IB) continued under British influence post-independence, functioning as MI5’s subordinate with a security liaison officer in New Delhi. The Indian Political Intelligence (IPI) had expanded significantly during World War II.

MI6’s attempt to establish covert operations in India failed when their agent was exposed in March 1948. Britain uniquely classified India as a foreign nation for intelligence purposes.

The Intelligence Bureau Director NPA Smith’s response to the 1946 Calcutta communal violence demonstrated British strategic calculations, advising against actions that could provoke anti-British sentiment.

Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), established in 1948, evolved into a strategic entity under Lt. General Ghulam Jillani Khan, aligning with British interests.

The intelligence power transfer differed from political decolonization, with Britain considering covert operations in independent India, viewing it as a crucial Cold War asset. The IB’s continued alignment with British priorities created tension with Nehru’s policies.

Money Matters Behind the New Borders

British India’s economic structure influenced partition boundaries significantly. Through taxation and unfair trade, Britain extracted wealth that fuelled its industrial revolution. India’s global economic share plummeted from 24.5% pre-British rule to 4.2% at independence. British extraction totalled INR 3797.12 trillion, equivalent to 17 times the UK’s current GDP.

The partition impacted agriculture severely. Of undivided India’s 70 million irrigated acres, India retained 48 million while Pakistan received 22 million, causing food grain deficits and disrupting cotton and jute supplies.

The industrial division revealed stark imbalances, with India retaining most industrial zones while Pakistan received primarily agricultural areas . Pakistan became dependent on India for essential supplies like cotton goods, sugar, coal, and steel .

The partition allocated Pakistan 17.5% of British India’s assets and liabilities, including Rs 75 crore from India’s central bank reserves of Rs 400 crore. Financial disputes continue, with India claiming Rs 300 crore and Pakistan countering with a Rs 560 crore claim in 2014.

Post-partition trade disruptions severely impacted the region. Indian ports lost their role as export hubs when Pakistan denied transit access. Worker migration led to factory closures, with railway staff declining 45%.

The partition’s economic impact continues to influence South Asia’s development, with both nations starting equally underinvested but following divergent paths.

Finally It Was Done

Britain’s partition role extended beyond religious divisions, involving strategic, intelligence, and economic control. Their intelligence operations shaped Pakistan’s security framework, with MI5 and MI6 training ISI operatives.

Pakistan’s creation served Britain’s Cold War interests by establishing a buffer between Soviet influence and India, while Afghanistan was positioned as a strategic point between Russia and West Asia. These strategic decisions continue to influence South Asia’s geopolitical dynamics.

The British approach to partition’s economic aspects was equally calculated. Their border planning created Pakistan’s dependence on India for industrial products while controlling vital agricultural resources. This economic disparity, along with colonial-era wealth extraction, influenced both nations’ development paths.

Often, India’s partition in 1947 is viewed simplistically—as merely a conflict driven by ambition for the Prime Ministerial position or as a consequence of deep-rooted Hindu-Muslim divisions. However, what truly lay behind the curtain was a cunning British strategy carefully designed to preserve their strategic influence and economic dominance in the subcontinent, creating enduring divisions that continue to shape South Asian geopolitics even today.

It was a truly insightful and exceptionally well-articulated read—your analysis is both compelling and enlightening. I fully agree with your perspective. One key takeaway that strongly resonated with me is the recognition that the partition of India was not merely the result of Hindu-Muslim differences, but a deliberate British strategy aimed at creating division and sustaining control through fragmentation.

It also prompts a deeper historical reflection: why was Cyril Radcliffe—a man entirely unfamiliar with the Indian subcontinent—given the immense responsibility of drawing borders that would shape the fate of millions? The consequences of such decisions are still felt across the region.

As an Afghan, I cannot overlook a parallel act of colonial imposition—the Durand Line. The decision by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand to arbitrarily draw a boundary between Afghanistan and British India not only violated Afghanistan’s territorial integrity but also severed deeply connected ethnic, cultural, and historical regions such as Pukhtunkhwa and Balochistan. These areas, rich in identity and resilience, were unjustly separated and continue to suffer under policies that echo colonial-era suppression.

The legacy of such British decisions has caused profound and lasting harm. Communities divided by artificial lines still struggle with marginalization and the denial of fundamental rights. Your work highlights the necessity of revisiting these historical injustices with both honesty and urgency.

Thank you Mr. Varun Chaturvedi for shedding light on this crucial subject.