Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

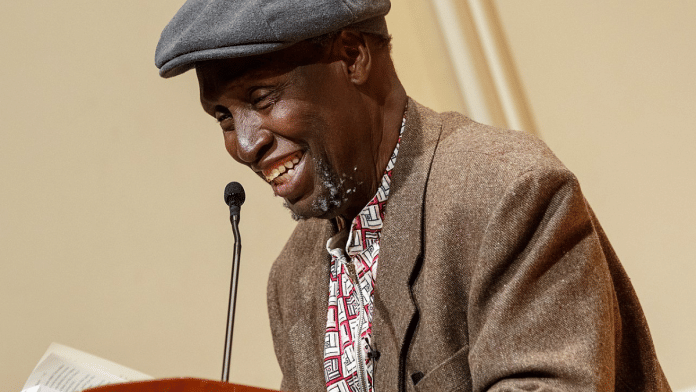

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a Kenyan writer and academic, born on January 5, 1938, in Kamiriithu, Kenya. He has carved an indelible place in global literature as a writer, thinker, and cultural activist. He’s one of Africa’s most prominent literary figures, known for his novels, essays, plays, and short stories that explore themes of colonialism, cultural identity, and resistance. In the 1970s, he made a revolutionary shift. He rejected English as his medium of expression and embraced his mother tongue, Gikuyu, reclaiming not only his language but also his identity. He changed his name to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o—a powerful act of cultural resistance against linguistic imperialism. He believed that language is not just a tool of communication, but a carrier of culture, memory, and worldview. Through this lens, he challenged the dominance of colonial languages. His writings: novels, plays, essays, or memoirs etc. continue to explore themes of colonialism, resistance, and post-independence disillusionment.

Beyond literature, Ngũgĩ has made profound contributions to academia. He has taught at

leading institutions including Yale, New York University, and the University of California,

Irvine, where he has helped reshape the fields of postcolonial theory and comparative

literature from a distinctly non-Western perspective.

Early Literary Contributions

His early novels such as Weep Not, Child and A Grain of Wheat gave voice to the

complexities of colonial rule and the struggle for Kenyan independence. But what makes

Ngũgĩ truly unique is not just the power of his storytelling but the courage of his convictions.

As his critique of colonialism deepened, he questioned the use of colonial

languages—especially English—as the primary medium of African literature. Colonial

languages like English, imposed during and after colonization, continue to dominate the

spheres of education, governance, and media. For Ngũgĩ, this is not mere linguistic

preference—it is a mechanism of control. These languages alienate individuals from their

indigenous histories, their ways of knowing, and their cultural identity. They erase, fragment, and replace what was once rooted and whole.

This conviction became action in 1977, when he co-authored and staged Ngaahika

Ndeenda—I Will Marry When I Want—a powerful play written and performed in Gikuyu, the

language of his people. The play exposed the injustices of land exploitation and class

oppression in post-independence Kenya. Its impact was profound—and so was the

government’s response. Ngũgĩ was arrested and detained without trial. But even in prison, he refused to be silenced. In a powerful act of resistance, he wrote his next novel, Devil on the Cross, on prison toilet paper—his first work composed entirely in Gikuyu. This was more than a literary milestone. It was a radical declaration of cultural sovereignty.

Ngũgĩ’s commitment to linguistic decolonization was articulated most powerfully in his 1986

essay collection, Decolonising the Mind. In it, he argues that language is not simply a tool for communication—it is a carrier of culture, a vessel of memory, and a battleground of

ideology. He argues that true liberation from colonialism is not complete until we decolonize

our language, our culture, and our consciousness. For African writers, reclaiming indigenous languages, he said, is not just an artistic choice—it is an act of resistance. He began to challenge not just political oppression, but also linguistic domination. For Ngũgĩ, writing in a foreign tongue was not a neutral choice….. in fact it is a form of cultural dependency.

He argued, that language is is the vessel of memory, culture, and power. To reclaim our indigenous languages is to reclaim our agency, our dignity, and our future. Ngũgĩ wa

Thiong’o’s life is not only a testament to the power of words—it is a chronicle of resistance,

even in exile. Following relentless government repression in his homeland, Ngũgĩ was forced into exile—first in the United Kingdom and later in the United States. But exile did not silence him. On the contrary, it became a new stage from which he amplified his critiques and continued to produce powerful work. His later novels, such as Wizard of the Crow (2006), blend magical realism, satire, and political allegory to examine corruption and tyranny in fictional African states that mirror real-world conditions. Through such storytelling, Ngũgĩ transforms literature into a revolutionary act and reminding us that fiction, too, can be a weapon of truth.

Today, in 2025, his messages are of utmost importance to emulate —especially in the Global South. Ngũgĩ’s ideas are nothing short of a blueprint for intellectual sovereignty. He calls on us to embrace our identities with pride, to dismantle systems that marginalize local

knowledge, and to foster equitable structures that reflect the dignity and diversity of our

peoples. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and Indigenous Oceania,

communities are still navigating the enduring structures of neo-colonialism, foreign debt

traps, exploitative trade agreements, extractive industries, and cultural imperialism. These are not merely economic or political challenges rather they are narrative battles. Battles over whose stories are told, in what languages, and for whose benefit.

Let us celebrate his legacy not just in ceremony—but in commitment. Commitment to

decolonizing our syllabi, our institutions, our communication, and our consciousness. Let us

make space for indigenous languages, for local knowledge systems, for the stories that

colonialism tried to silence but could never erase.

(The author is Assistant Professor, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi)

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.

Inspirational life described in a thoughtful and interesting manner.