By Niklas Pollard and Marie Mannes

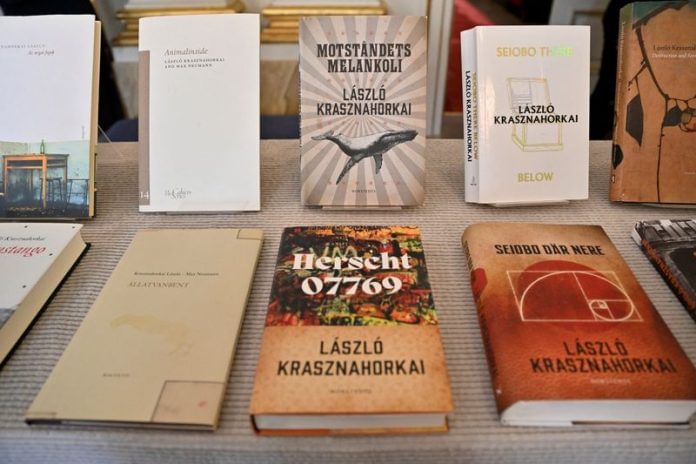

STOCKHOLM (Reuters) -Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday “for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”.

“Laszlo Krasznahorkai is a great epic writer in the Central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterised by absurdism and grotesque excess,” the Swedish Academy, which awards the prize, said in a statement.

“But there are more strings to his bow, and he also looks to the East in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone.”

TRAVELS TO CHINA AND JAPAN LEFT DEEP IMPRESSION

The settings of his novels move across central Europe’s remote villages and towns, from Hungary to Germany, before skipping to the Far East, where his travels to China and Japan left deep-seated impressions on Krasznahorkai.

The American critic Susan Sontag crowned Krasznahorkai contemporary literature’s “master of the apocalypse”, the Academy said, “a judgement she arrived at after having read the author’s second book Melancholy of Resistance”.

The second Hungarian to win the prize, worth 11 million Swedish crowns ($1.2 million), after Imre Kertesz in 2002, Krasznahorkai was born in the small town of Gyula in southeast Hungary, near the Romanian border.

His breakthrough 1985 novel, Satantango, is set in a similarly remote rural area and became a literary sensation in Hungary.

“The novel portrays, in powerfully suggestive terms, a destitute group of residents on an abandoned collective farm in the Hungarian countryside just before the fall of communism,” the Academy said.

Across the region, collective farms had been set up when farming land was confiscated at the start of communist rule, and many had become symbols of mismanagement and poverty by the time it ended in 1989.

“Everyone in the novel is waiting for a miracle to happen, a hope that is from the very outset punctured by the book’s introductory (Franz) Kafka motto: ‘In that case, I’ll miss the thing by waiting for it’,” the Academy said.

Krasznahorkai has repeatedly referenced “The Castle” by Kafka as a key influence.

“When I am not reading Kafka, I am thinking about Kafka. When I am not thinking about Kafka, I miss thinking about him,” he told the White Review in 2013.

CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED SCREEN ADAPTATIONS

Krasznahorkai had a close creative partnership with Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr. Several of his works have been adapted into films by Tarr, including “Satantango”, which runs to more than seven hours, and “The Werckmeister Harmonies”.

“When I read (Satantango), I knew it immediately that I must make a film based on it,” Tarr told Reuters by phone. “I am very happy… it’s hard to say anything right now.”

Their collaboration has garnered critical acclaim. In 1993, he received the German Bestenliste Prize for the best literary work of the year for “The Melancholy of Resistance”.

Krasznahorkai’s writing may resonate with readers immersed in news from Russia’s war in Ukraine or the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

“We seem to have entered the 21st century in a more hostile and bleak environment than we hoped for at the end of the 20th,” said Jason Whittaker, Professor of Communications at the University of Lincoln.

“So actually … some of the bleak and darkly comic elements of books such as Satantango actually will resonate with many more readers than previously.”

LITERATURE THE FOURTH NOBEL PRIZE OF 2025

Established in the will of Swedish dynamite inventor and businessman Alfred Nobel, the prizes for achievements in literature, science and peace have been awarded since 1901.

Past winners of the prize include French poet and essayist Sully Prudhomme, who bagged the first award, American novelist and short story writer William Faulkner in 1949, Britain’s World War Two Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1953, Turkey’s Orhan Pamuk in 2006 and Norway’s Jon Fosse in 2023.

Last year’s prize was won by South Korean author Han Kang who became the 18th woman – the first was Swedish author Selma Lagerlof in 1909 – and the first South Korean to receive the award.

Over the years, the choices made by the Swedish Academy have drawn as much ire as applause.

In 2016, the award to American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan sparked criticism that his work was not proper literature, while Austrian Peter Handke’s prize also drew criticism in 2019.

Handke had attended the funeral in 2006 of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, seen by many as responsible for the deaths of thousands of ethnic Albanians who were killed in Kosovo and the displacement of almost 1 million others during a brutal war waged by forces under his control in 1998-99.

Prizegivers have also in the past been accused of ignoring some of the giants of literature, including Russia’s Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, France’s Emile Zola and Ireland’s James Joyce.

($1 = 9.3420 Swedish crowns)

(Reporting by Simon Johnson and Johan Ahlander in Stockholm, Justyna Pawlak in Warsaw; additional reporting by Krisztina Than in Budapest, Terje Solsvik in Oslo, Greta Rosen Fondahn, Niklas Pollard and Marie Mannes in Stockholm; Editing by Alex Richardson)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Reuters news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.