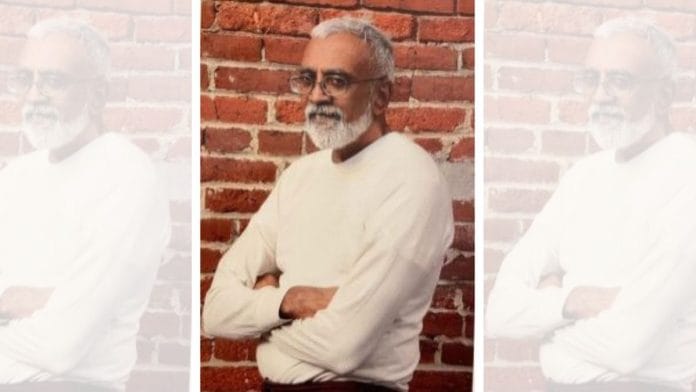

New Delhi: A 64-year-old Indian-born permanent legal US resident, Subramanyam Vedam, who has spent over four decades in prison for a 1980 murder in State College, was exonerated by a Pennsylvania court earlier this month in light of a suppressed FBI note, in a remarkable turn in the 40-year-old case.

However, after his release, Vedam was reportedly taken into the custody of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and faces possible deportation to India. Vedam’s legal team is fighting the deportation order.

In the 1980 murder case, Judge Grine of the Court of Common Pleas of Centre County concluded in a post‑conviction evidentiary hearing that the prosecutors violated Vedam’s due process rights by suppressing exculpatory evidence with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), allowing false testimony to go uncorrected.

“The Commonwealth violated petitioner’s due process rights and deprived him of a fair trial. Therefore, the court vacates the petitioner’s conviction and awards him a new trial,” the court stated.

On 2 October 2025, Centre County District Attorney Bernie Cantorna announced that his office was dropping the murder charges and would not pursue a new trial against Subramanyam Vedam after decades of incarceration. According to reports, Vedam was released from prison in the murder case on 3 October 2025.

1980 murder case

When Subramanyam Vedam was 20, he was charged with the murder of his classmate, Thomas Kinser, who disappeared from State College in late 1980.

Kinser’s remains were found in September 1981 in a wooded area, with a bullet hole in the skull. Police recovered a .25-calibre shell casing, and the Commonwealth built its case around the theory that Subramanyam Vedam had shot Kinser with a .25-calibre handgun.

A public witness, Daniel O’Connell, testified that he sold Subramanyam Vedam such a weapon at least a week before Kinser was “last seen” and that Vedam test-fired it behind a Wendy’s restaurant.

Subramanyam Vedam was convicted of first-degree murder in 1983, retried and convicted again in 1988, and sentenced to life imprisonment. In 1984, as part of a separate plea, he also received a term of two and a half years on a drug offence, to run concurrently.

The central issue at both trials was whether a .25 calibre bullet could have caused the wound observed in Kinser’s skull—a question that the suppressed FBI data would have directly answered.

Also Read: Trump wants a deal with Taliban to get Bagram back. Here’s why this airbase in Afghanistan matters

Suppressed evidence

In Brady v. Maryland (1963), the US Supreme Court established that a prosecutor’s suppression of evidence, favourable to the accused, violates due process, regardless of whether the suppression was intentional or inadvertent.

Such evidence—known as Brady material—includes any information that is exculpatory or could impeach the credibility of prosecution witnesses.

The court’s findings centred on two major Brady violations—the Commonwealth or state government’s suppression of handwritten FBI measurements of the bullet hole in the victim’s skull and the Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) data that contradicted the prosecution’s forensic theory.

The Brady case “makes it clear that the due process rights of the accused are violated if the government fails to disclose before trial, either intentionally or inadvertently, the existence of material evidence favourable to the defence”.

The court also noted, “There are three necessary components that demonstrate a violation of the Brady strictures: the evidence was favourable to the accused, either because it is exculpatory or because it impeaches; the evidence was suppressed by the prosecution, either willfully or inadvertently; and prejudice ensued.”

Ultimately, the court agreed with Vedam that “failure to disclose this information is a Brady violation”. Both pieces of evidence that directly undermined the state’s claim that a .25 calibre handgun caused the fatal wound were, for decades, withheld from the defence. From prison, Vedam had maintained his innocence and continued to appeal against his conviction on circumstantial evidence.

In Napue v. Illinois (1959), the US Supreme Court ruled that a conviction obtained through false testimony—known by the prosecution as false—violates due process, even if the falsehood goes only to the credibility of a witness.

This principle was reaffirmed and expanded in later rulings, including Glossip v. Oklahoma (2015), which underscored that prosecutors have a duty not only to avoid presenting false evidence but also to correct any misleading testimony once it becomes known.

Judge Grine noted that the “Commonwealth’s failure to comply with its obligations under Brady and Napue/Glossip regarding the FBI measurements and its Brady obligations regarding the NAA data” entitled Vedam to a new trial.

The court described the Commonwealth’s conduct as a “gross distortion of the Brady doctrine”.

Revelations in FBI note

One of the most striking findings of the court concerned a handwritten FBI note—suppressed for decades—that documented precise measurements of the bullet hole in the victim’s skull.

At the 1988 trial, FBI Agent Albrecht, a key prosecution witness, testified that he had measured the skull hole and found nothing inconsistent with a .25 calibre bullet. However, the FBI’s own handwritten measurements, not disclosed until January 2024, showed that the hole was smaller than the standard size of such a bullet.

The court found that the standard size of a .25 calibre bullet is 6.35 millimetres, while the hole in the skull measured between 5.9 and 6.1 millimetres, so a .25 calibre bullet could not have caused the wound.

“The suppressed evidence would have significantly bolstered the defence’s argument that a .25 calibre gun could not have been the murder weapon,” the court observed.

The court also held that Agent Albrecht’s false assurance of consistency violated due process under Napue v. Illinois and Glossip v. Oklahoma, as the prosecution had been aware of the actual measurements but allowed the misleading testimony to stand.

Withheld NAA data

The second major due process violation involved the Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA), conducted by the FBI. Neutron Activation Analysis, in forensic investigations, can identify whether two bullets came from the same batch of ammunition by comparing their trace elemental makeup. The FBI had conducted an NAA to compare the bullet recovered from the victim’s remains with a test-fired bullet allegedly linked to Vedam.

Although Agent Albrecht signed the results, the underlying NAA data was not disclosed to the defence until February 2025—over four decades after Vedam’s arrest.

An expert review of the data concluded that the two bullets were “so disparate that it increases the likelihood that the bullets are from different boxes of bullets,” undermining the prosecution’s claim that the same firearm had fired both.

The court held that the NAA data “undercuts the purported inculpatory value of the bullet recovered with Kinser’s remains by weakening the ‘match’ that Agent Albrecht sought to establish.”

‘Different result possible’

Citing Brady v. Maryland (1963), the court reaffirmed that due process requires the prosecution to disclose material evidence favourable to the accused, whether exculpatory or impeaching.

“Failure to disclose this information is a Brady violation,” the court held, concluding that “there exists a reasonable probability that its disclosure would have produced a different result at trial.”

The opinion emphasised that the withheld measurements and NAA data collectively undermined the prosecution’s entire forensic theory linking Vedam to the killing.

Given the cumulative effect of the suppressed evidence, the court vacated Vedam’s 1988 conviction and ordered a new trial under the Pennsylvania Post-Conviction Relief Act (PCRA). The matter had come up on the criminal pre-trial list for the December 2025 term.

However, before retrial proceedings could begin, District Attorney Cantorna announced that the state government would not retry the case, acknowledging that after four decades, the prosecution could no longer proceed.

“The Commonwealth’s suppression of the handwritten note containing the FBI measurements and the full FBI file deprived the petitioner of a fair trial,” the court declared, giving a stark reminder of the importance of prosecutorial transparency and the constitutional duty to disclose exculpatory evidence.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Good progress achieved in trade negotiations, says Modi after his second call with Trump in a month