Lebanon is a tiny country of about 10,400 sq km which is almost exactly, to the last decimal point, the size of Tripura and has, at this point, just over 50 lakh very talented people with very high social indicators but a really wrecked economy.

Lebanon has followed a system called the confessional system. Confessionalism is something that comes out of the Turkish-Ottoman tradition, where nationalism was not so well developed as yet, even ethnicity was not so well developed, but religion was.

A concept developed that people were linked together by similar religious beliefs. You can be, for example, a Muslim but then you can have several variants there. But if there is sufficient similarity or sufficient uniformity among those faiths or beliefs, then you could be ranked together or grouped together because you were then considered to be the people of the same confessional community. These confessional communities then made a unit.

In a way, this is a de jure, this is a legal way of mixing religion and politics.

This is exactly contrary to the constitution of most modern countries which don’t mix religion with politics. Whereas a confessional system or a confessional constitution, as is the case in Lebanon, by law and by constitution mixes religion with politics.

That is what makes Lebanon stand apart from many of the other democracies. In fact, it must be one of the rare ones that we have seen. I know that in 2003, in Iraq, at one point, some similar system was set up between various sects and communities to bring about some kind of power sharing and stability. But later, a more proper democracy came.

Also Read: Amid Israel-Hezbollah clashes, a look at UN peacekeeping force in Lebanon & India’s contribution

French mandate in Lebanon

The French got a mandate for Lebanon in 1923 after the first World War, when the Ottoman Empire was divided.

A lot of the problems that we see in the Middle East right now came up after the Ottoman Empire declined. That is not to say that when the Ottoman Empire was there, there was perfect peace and harmony and happiness because many of these regions were colonised, they were part of the Ottoman Empire. And no colonial power is a nice guy.

After the Allies won the war, in 1923, they carved up the Middle Eastern region among themselves. The authority or the power they got over the region, that was called mandates. The French got the mandate over Lebanon. In 1943, the French mandate ended and Lebanon came up as a more distinct country.

Lebanon was a very diverse country, which had a dominant Christian population but not in majority. The larger numbers were still Muslims. And among Muslims also, there were Shias and Sunnis.

The fact is that in 1943, when they were trying to create this new nationalism and this new nation, they decided that to keep it together, they will follow the system of confessionalism. What that means is each community will have power according to their own numbers.

Division of power in Lebanese political system

This division was cut very fine. The largest section of Christians in Lebanon is Maronite Christians — about 52 per cent.

About 30-32 per cent of Lebanon’s population is now Christian, but it might have been more in 1943 because Muslim numbers have gone up since. Of the 32 per cent or so Christians, more than 52 per cent are Maronite Christians, who are a branch of Catholics. They follow the Syriac tradition and use the Syriac language above Latin. The tradition they come from — the Syriac tradition — has similarities with Syrian Christians in Kerala. Although, Syrian Christians in Kerala do their service in Malayalam.

These Maronite Christians, although they are Catholics, they are also different from our traditional understanding of Catholics. For example, their priests can marry and their monks and nuns live in the same place.

Maronite Christians were given the pride of place in the system whereby they would always have the President. The Sunni Muslims would have the Prime Minister, and powers were divided between the President and the Prime Minister. Shias get the Speaker of the House. The Deputy Prime Minister and Deputy Speaker were both given to Eastern Orthodox Christians. That was the system Lebanon began with. And it’s a system which principally still exists, although there have been changes.

Although very provocative if not risqué, doesn’t it sound like the demand that we’ve seen lately in India: “Jiski jitni sankhya bhari, uski utni hissedari?”

I’m not saying that what happened in Lebanon is an example for India. But what happened in Lebanon is a case study which cannot be missed because Lebanon right now is a broken country. It’s a country where population has come down, where inflation was running at 171 per cent in 2022. Its currency has been declining rapidly. Its debt-to-GDP ratio is among the highest in the world. Among the major countries, it is the third highest in the world.

Its talent has been leaving the country. Large parts of the country are controlled by warlords and militias. We know that all of southern Lebanon is controlled by Hezbollah militias. The Hezbollah is a regular party in Lebanon that has 13 members in the 128-member national parliament. It also had ministerial positions. Thirteen members is a lot because almost no single party has members reaching the 20-member mark.

Lebanon is now caught between several proxy wars. The Israelis and the Syrians are fighting each other there. The Saudis and the Iranians are fighting each other there. There’s a Syrian-Iranian axis which controls large parts of Lebanon. There’s a Saudi-US axis that controls another large part of Lebanon, and you can see who might be linked with whom.

If Hezbollah is a Shia organisation, it will be closely linked with the Syrian-Iranian axis. The Christian groups will be closer to the Western axis and then where do the Sunnis go? Sunnis, a lot of them are very close to the Palestinians, they don’t like the Israelis but they don’t like Shias either. That is where the Saudis also come in.

Lebanon now is so broken that since the winter of last year, they haven’t even had a President. The last President was Michel Aoun, who is a former army general. He was an elected president. The country also has a caretaker prime minister. How else do you define a failed state? Maybe it still does not pass some final parameter of being called a failed state. But in my book, if you want to see a failed state, this is an example.

And one of the reasons this has happened is that the country as it was founded, embraced sectarianism, embraced constitutionally the idea of mixing religion with politics and also constitutionally embraced the idea of dividing power based on each one’s sectarian identity.

What is sectarian can be caste in the case of India. When you say “Jitni jiski abadi, utna uska haq”, you have to be careful. Of course, in India, there is Hinduism, there is Islam, there is Sikhism, there is Christianity. These are overarching religious identities. Also, Indian nationalism is much better developed than Lebanese nationalism at any point of time. So, we don’t have to overinterpret the Lebanese situation and become paranoid. But there is an example that we must look at because this cascaded down.

Also Read: How Gaza hospital blast united Arab world against Israel amid Tel Aviv’s attempts to normalise ties

Constitutional sectarianism

The positions of President, Prime Minister, Speaker of the House, Deputy Prime Minister, Deputy Speaker — these were all divided on sectarian basis. Not just that, even seats in Parliament were divided. You might say they were divided according to the population, but it wasn’t that clear simply because the Christians were the dominant population. They punched above their weight in the distribution of powers.

Almost everything, government jobs, government positions, was divided on the same basis.

Now you see how this is divided. Maronites account for 21 per cent of the overall population, and more than half of all Christians, which includes Greek Orthodox (8 per cent), Melkite (5 per cent), Protestant (1 per cent) and non-native to Lebanon Christians (6 per cent). These numbers can be very dodgy, though, because they have been changing over the decades. We’ve seen the flight of a lot of talent from Lebanon and the flight of a lot of the Christian community.

At the same time, people from other sects and religions have tried to increase their numbers. There’s been a race to produce more babies. And then there are soft unprotected borders. Shias can bring in more Shias from the Syrian side, Sunnis can bring in more Sunnis from the Israeli side, or the Palestinian side. That’s how demographic balance has also been changing for a long time.

The overall population of Muslims can be anything between 62-67 per cent, depending on how you count. Overall, let’s say about 31 per cent are Sunni and about 31 per cent are Shia. One gets the Prime Minister, the other gets the Speaker. And then similarly, there is a division in Parliament.

Then, among the Shias, there is also a 6 per cent group of Alawites — a sect of Shias. They are a small group, but they are represented in this region by the ruling dictatorial dynasty of Syria. Assads are Alawites.

There is also a 5 per cent population of the Druze community. The Druze, by and large, define themselves as monotheistic people. And because they were always a minority, if they were in a Christian village, they followed the Christian method of praying; if they were in a Muslim village, they followed the Muslim method of praying. Over time, however, they are increasingly counted as Muslims. Although among devout and conservative Muslims, they are victimised because they are seen like Ismailis because they don’t follow all of the principles of traditional Islam.

National Pact of 1943 & the Taif Accords

How does it work in the National Parliament? The first division of the spoils, or of the power base in Lebanon, came up after what was called the National Pact in 1943 that established the modern state of Lebanon.

That carried on. By the mid-1950s, trouble had already started because Britain and France had started playing games. There was conflict over the Suez Canal. The Lebanese leadership did not condemn it and because of that a lot of the Muslim groups got upset.

After that, in stages, the civil war started. Between the mid-1960s to 1975, there was instability, and from 1975 to 1990, a proper 15-year civil war took place in Lebanon. Everybody participated in that civil war — the big powers got involved, particularly the US. Iran also got involved as did Saudi Arabia and Israel.

It was within that period, in 1982, that Israel carried out an invasion of Lebanon because they were so hassled by what was happening in southern Lebanon with Hezbollah. The Israeli armed forces reached close to Beirut, and parts of Beirut were shelled by Israeli artillery.

At the end of this, there were a bunch of peace accords signed between the various warring communities. These were the same warring communities that Lebanon’s confessional system was supposed to prevent from fighting each other. That system was supposed to bring them together and create nationalism. It completely failed to do so. These agreements are called Taif agreements.

Taif, a place in Saudi Arabia, was where these agreements were signed. And these agreements — among the many changes that the various factions demanded — resulted in changes in the composition of the National Parliament because, after all, the Muslim groups wanted more seats.

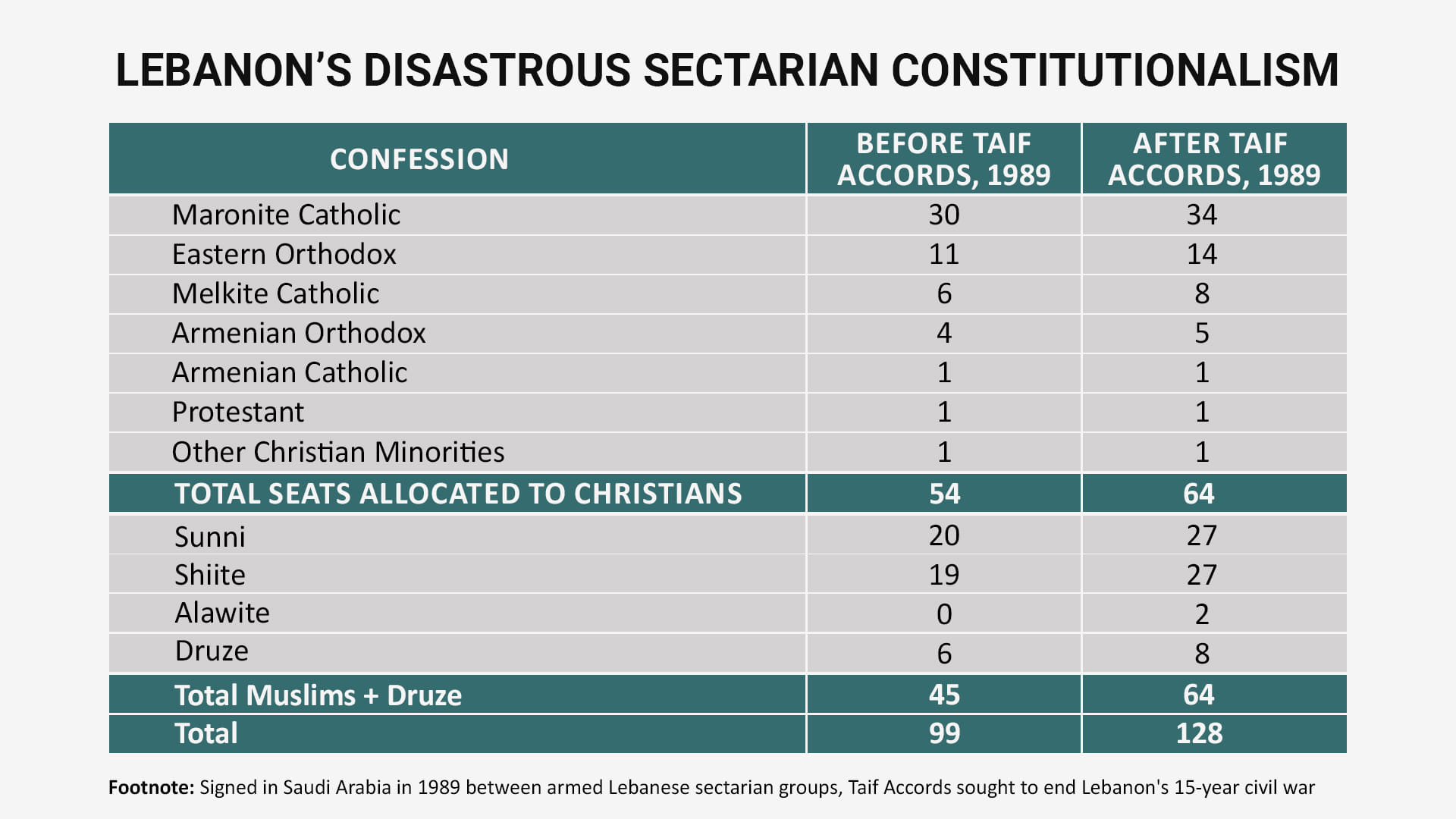

Before the Taif Accords, the strength of the parliament was 99. Of these, Christians of various denominations had 54 seats — a clear majority also, although they were not the majority population — and Muslims 45. That is how this was ordained or decided in 1943. After the Taif Accords, the strength of parliament increased to 128 seats from 99. The division of power now became equal: The Christian groups got 64 and Muslim groups got 64.

How has it worked for Lebanon since then? For long periods, Lebanon hasn’t had a government. At this point, it effectively does not have a government, does not have a president, the prime minister is a caretaker. For several years in the middle, Lebanon has missed an election, missed having a president. It has also had a prime minister assassinated — Rafik Hariri. Later, his son, Saad Hariri became prime minister. But he was removed. It was widely believed in 2017 that he was detained in Saudi Arabia, but he resigned. That led to more instability.

The Taif Accords and this kind of perfect division of power and political spoils has also not led to any unity.

This is how the numbers stack up in the new Parliament. Today, in a House of 128 seats, Christians have 64, of which Maronites have 34, Eastern Orthodox have 14, Melkite Christians have 8, Armenian Orthodox Christians have 5 and Armenian Catholic Christians, Protestants and other Christian minorities have 1 each. These add up to 64 seats of the Christian block.

Among the Muslims, this is the division: Sunnis have 27 seats, Shias have 27 seats, Alawites have 2 and the Druze have 8. That adds up to 64.

Also Read: How India voted at UN General Assembly on Israel-Palestine issue over the years

India not comparable to Lebanon

This is a very interesting example. No other country has done it. A history now of 80 years — exactly 80 years since this National Pact came into being in 1943 — shows that this proportionate division of political power, spoils, jobs, responsibilities, economic resources, etc. does not work.

Once again, the one reason it did not work in Lebanon is that before the National Pact and the creation of the new state in 1943, there wasn’t really an established Lebanese nationalism. Instead, there were these confessional communities, as if going back to Ottoman times. But in the Ottoman times there was an emperor. And if anybody misbehaved, the consequences were quite terrible.

Don’t import this disaster directly into the Indian situation, because India has, as I said before, many overarching identities. There are religions across the country, there is a secular Constitution, there is also a very strong Indian nationalism. Under no circumstances can the Indian situation be comparable to Lebanon at any point of time, because India begins with a strong nationalism…not today, not 100 years back, not 200 years back, but for a very, very long time. We have to keep that reality in our minds before we start getting neurotic about this.

But, at the same time, the fact is that the idea of just counting people and dividing them — in this case, based on religion and sect; tomorrow, it can be caste, day after it can be ethnicity, tribes, regions, linguistic groups — and distributing spoils according to the numbers takes away competition among people from various communities, but competition is how merit emerges.

That’s not to say people of a certain caste have more merit and certain caste have less merit. Rather the people of all castes and all ethnicities, all religions, all linguistic groups must compete fairly. At the same time do you need to know who’s who if there are deep injustices running in your society? Yes, you need to know who’s been left behind and who suffered discrimination and who now needs a fairer share of the national spoils or opportunities.

We have to look at this with a great deal of wisdom and patience. At the same time, there is no harm drawing some lessons from an unfortunate but highly-talented, beautifully located state called Lebanon.

This is the edited transcript of ThePrint Cut The Clutter Episode 1331 published on 17 October 2023.

Also Read: What, when, where, why & how of the Israel-Hamas war