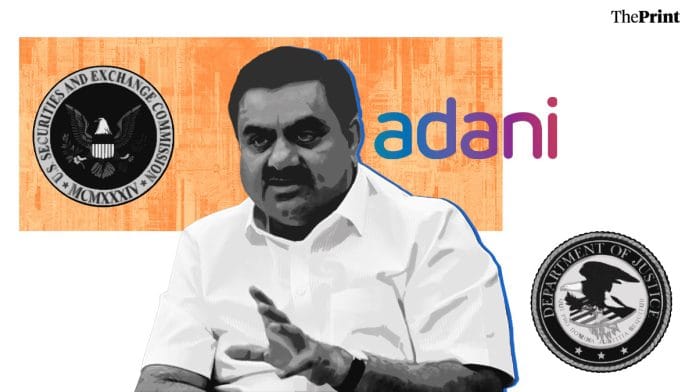

The US Security and Exchange Commission’s indictment of Adani Group chairman Gautam Adani and two others has led to questions about how or why the American government launched an investigation into charges of bribery involving an Indian conglomerate and Indian government officials. In this episode of ThePrint Explorer, Praveen Swami looks at the extraordinary legislation underpinning this: the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, or FCPA.

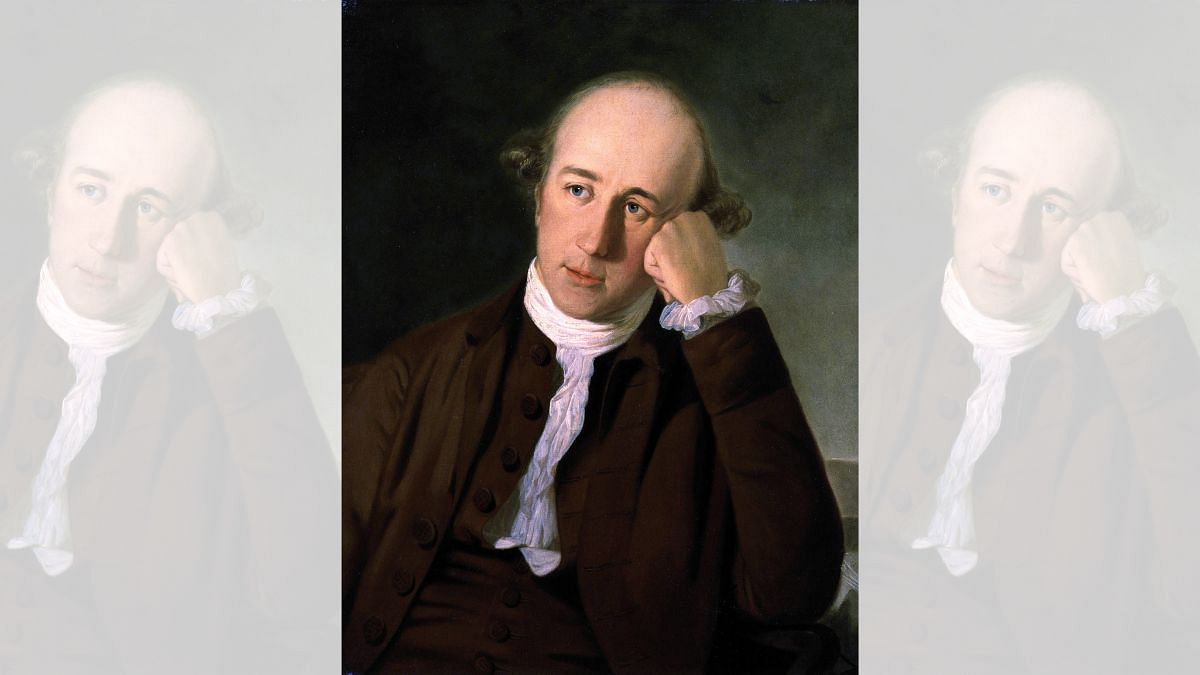

Washington DC: Elegantly dressed in a perfectly tailored white suit, Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld, consort to the queen of the Netherlands, brushed past the waiting journalists: “I am above such things,” he snorted. The stains on his character, though, were visible to all. There was the luxury apartment he had purchased in Paris for his mistress, Hélène Grinda, a string of dalliances with other women, and his past membership of the German Nazi Party. And there was one more thing, a hammer pounding on his reputation so hard it threatened to bring the edifice down.

In 1974, Prince Bernhard had secretly written to the American aircraft giant Lockheed Martin, demanding $1.1 million on an upcoming purchase of fighters by the Dutch Government. As Inspector-General of the Dutch Armed Forces, he had the ability to make or break the deal, and Lockheed complied.

Across the Atlantic, the United States Senate’s Banking Committee had noticed the payment, as it held hearings to understand why Lockheed was going into its 1975 stockholders’ meeting with unaudited financial statements. Lockheed, Senator William Proxmire soon discovered in the hearings, had paid hundreds of millions of dollars through consultants to government officials in Saudi Arabia, Japan, Italy, and the Netherlands. Among the recipients was Prince Bernhard.

Asked about that payment by a Senate committee in 1976, then Lockheed president Carl Kotchian replied: “I think, sir, that as my understanding of a bribe is a quid pro quo for a specific item in return…. I would characterise this more as a gift. But I don’t want to quibble with you, sir.”

The previous year, Lockheed’s vice-president and treasurer Robert Waters had died by suicide. Eli Black, chairman of United Brands Corporation, jumped to his death from a New York skyscraper, as the Securities and Exchange Commission discovered that his corporation, the largest American banana producer, had paid $2.5 million to senior politicians in Honduras.

The bribe’s role in capitalism

For decades before the Great Rebellion of 1857 finally evicted the East India Company from its possessions, the greatest multinational corporation of its time repeatedly petitioned the Crown for money: Its predatory trade forced it to spend on forts and soldiers to fight endless wars against competitors, and expand the frontiers of its trade monopolies.

As would ruin England to lose her Empire in India … it is threatening our own finances with ruin, to be obliged to keep it.

John Dickinson, a contemporary writer on India

Karl Marx—yes, the same guy who later wrote the Communist Manifesto and was a far better historian, in my view, than prophet—offered this analysis: There exists now a national debt of 50 million pounds, a continual decrease in the resources of the revenue, and a corresponding increase in the expenditure, dubiously balanced by the gambling income of the opium tax, now threatened with extinction by the Chinese beginning themselves to cultivate the poppy.

The reason the East India Company managed to persuade the Crown to pay for its adventures was pretty simple. The Company happily bribed the king and key aristocrats, while its own bosses, famously Warren Hastings, fed at the trough of the revenues from India. Though Hastings was acquitted of corruption, historian John T. Noonan Jr notes, he remitted home at least £218,527 during his ten years in office, or some ten times his annual salary.

And this is how mercantilism worked: You paid up a share of your profits for the privilege of doing business. You paid tax to the sovereign, but also bribed everyone who could stand in your way. Call it a gift, if you wish. And, mostly, the system worked. Elizabeth I’s key bureaucrat, Francis Walsingham, was notoriously corrupt—but he was also fantastically efficient, and no-one seemed to mind if he made a few bucks along the way. Poverty was for peasants, and priests.

Then, as capitalism evolved and became more structured, this way of doing business became a problem. The principle of capitalism was that markets should be independent entities. A bribe shouldn’t settle whether someone purchased Product A or Product B; that should happen because of the price and quality of those goods. And a bribe shouldn’t settle if Company A or Company B got a contract. That made nonsense of the whole idea of free trade.

Following the Great Depression which came close on the heels of the stock market crash of 1929, the business of regulating capitalism became all the more important. The US Securities and Exchange Commission—the institution now prosecuting the Adanis—was founded in 1934, under the Left-leaning President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The framers of the SEC Act argued that there was a close connection between protecting investors and maintaining a healthy economy.

The SEC’s mandate dramatically expanded from 1937, under future Supreme Court judge William Douglas, with the organisation restructuring power utilities, imposing rules on over-the-counter securities dealers, and setting up uniform accounting standards for publicly-owned companies.

Even though the New York Stock Exchange pushed back, it lost the argument. After its former president, Richard Whitney was caught embezzling from the NYSE’s fund for support of the widows and children of deceased stock exchange members, Douglas was able to impose the SEC’s will on important stock exchanges across the country.

From the 1980s, the SEC’s powers were curbed, and it increasingly withdrew from oversight of big financial institutions—a decision some say enabled the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. That’s another story, though, which isn’t very relevant here, and I’m not particularly competent to tell. There was something else, though, that would take the whole anti-corruption issue to another level.

The Watergate Fallout

Until 1974, when US Senator Frank Church held hearings into bribery by American corporations, corruption was considered pretty much a normal element of doing business—just lubricating the wheels of commerce and industry, many called it. American companies were furious with the move towards FCPA, which they thought would force them to operate with one arm tied behind their back. To Senator Church and others, though, it seemed such a law was necessary to protect and defend the entire architecture of free trade.

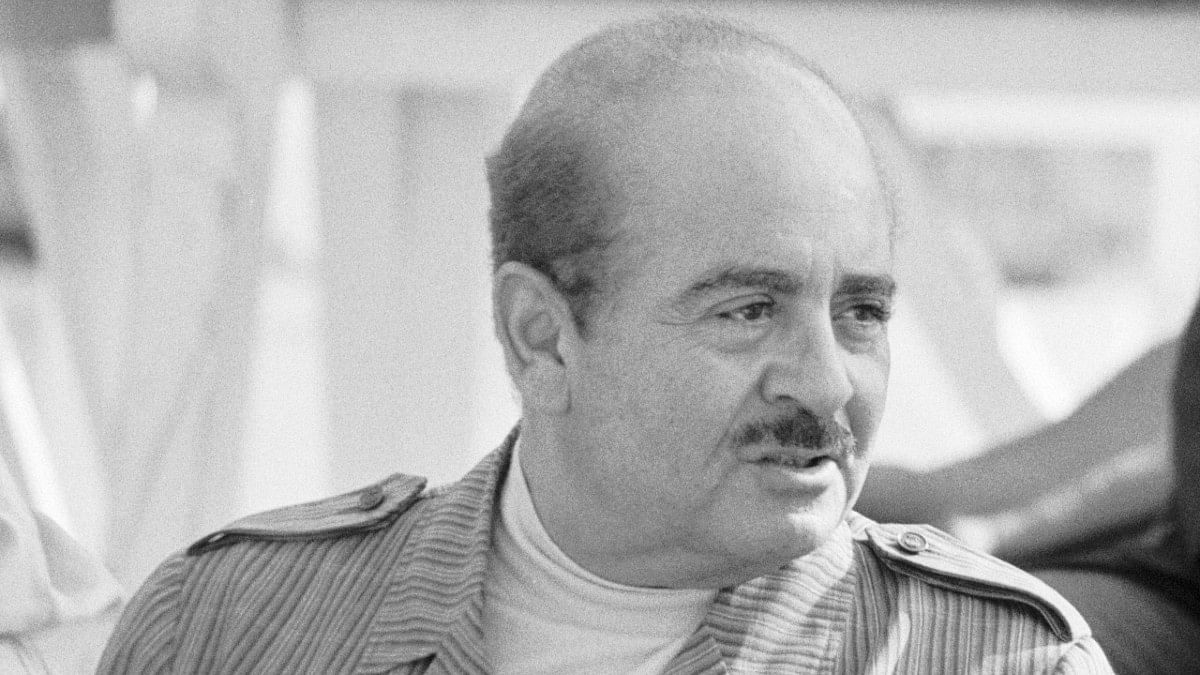

Late in the summer of 1975, Senator Church’s Senate Committee was investigating the sharp rise in oil prices which had come about after the Israel-Arab war in 1973, and the energy embargo which followed it. The Committee discovered that Northrop, a major supplier of military aircraft to Saudi Arabia, had been paying bribes to a Saudi arms dealer, the infamous Adnan Khashoggi. The committee learned of something called the “Lockheed model”—an institutionalised system of paying bribes across the world.

To secure a sale of its Lockheed L-1011 TriStar passenger jets to All Nippon Airways, it turned out, the company had made $2 million in payments to a convicted war criminal, and right-wing fixer, Yoshio Kodama. Kenji Osano, a businessman known for his political connections, and the Marubeni trading company, which represented Lockheed sales, were also involved. The code name “Peanuts” was used on receipts to indicate payoffs.

Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office’s arrest of former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka on suspicion of violation of the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act. It was the first time in history that a former prime minister was arrested for a crime committed during his tenure. There are still lots of conspiracy theories around what happened, to the effect that the US wanted to go after Tanaka. There will be similar ones in India now.

To understand why all this happened, you have to go back to 1972, when operatives working for President Richard Nixon, then engaged in his election campaign, were caught burgling the Democratic party’s headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington DC. That was a straightforward case of political espionage, but Senate investigations led on to a network of illegal campaign contributions made by top American multinationals to Nixon.

One of the corporations, Gulf Oil, provided an amazing report to a Senate subcommittee that detailed an elaborate overseas network to syphon political bribes back to the United States and to other countries. Gulf had apparently distributed more than $5 million to influential politicians.

Following its investigation into Gulf Oil, the SEC sent a questionnaire to American companies and asked them to reveal any “questionable payments” made by them abroad. Based upon this survey, the SEC published a report showing that over 400 US-based companies, including 117 of the Fortune 500, had made “questionable payments” totalling more than $300 million.

The legal scholar Mike Koehler has written a riveting account of the debates which followed. Even as some diplomats and corporate leaders argued that they were being pilloried for universal business practices, others argued that the costs outweighed business interests.

Representative Robert Nix and Representative Stephen Solarz—the latter an important friend of India—argued that American bribe-giving empowered Cold War enemies who cast the country as a rapacious economic predator. Large corporate interests, they argued, also undermined America’s foreign-policy goals, by helping keep unpopular regimes and rulers in power long past their sell-by date.

The payoff may cost a lot of money and still not work. You are paying off people who are dishonourable or they won’t accept the payoff. You may be double-crossed. The payoffs, while deferring the pressure for a time, may cause bigger problems later on for obvious reasons because of the illegality involved. It is bad economics, as well as bad morality.

Senator William Proxmire

Amid concerns that multinationals were subverting America’s democratic values and its free market principles, his supporters won the debate. The State Department and the Department of Defence resisted a unilateral ban on bribe-giving, but were overruled. There was also an effort to suggest some kind of voluntary disclosure system for overseas bribe-giving, but this was also shot down.

Finally, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed off on the FCPA. This was, it is important to understand, not just corporate regulation. Fundamentally, the FCPA sought to institutionalise American free-market principles and values within the global trade system. There have been a string of legislative interventions to strengthen that system since, notably the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which mandated rigorous practices for financial record keeping.

In essence, this body of legislation makes a simple point: If you want to play the game of global capitalism, you have to play by the rules, or risk a very sharp bop on the head by the umpire. Of course, corruption hasn’t been eliminated; far from it. But if you do get caught, there are consequences.

Also Read: Adani indictment shakes up Indian political & business worlds. The ball is in SEBI’s court

A global crackdown

Two key cases help tell us where things might go in the Adani case from here.

In 2016, the Brazilian firms Odebrecht SA and Braskem SA, big players in the petrochemicals and construction sectors, agreed to pay $3.5 billion in fines to settle their ongoing SEC case. The two firms, prosecutors alleged, ran a kind of ‘corruption department’, which paid out hundreds of millions of dollars to corrupt officials in Brazil. The funds were sent to politicians, political parties, and the state-owned petrochemicals giant, Petrobras.

Later, the supermarket giant Walmart and its wholly-owned Brazilian subsidiary were fined $137 million, for paying bribes to Brazilian officials. In this case, Walmart was accused of using third-party intermediaries—basically, subcontractors—to bribe officials to obtain the permits necessary to build and operate its stores. These practices had become commonplace among Walmart subsidiaries in Mexico, India, Brazil, and China.

In the case of India, the SEC said that Walmart subcontractors made “improper payments to government officials to obtain store operating permits and licenses”. These improper payments were then falsely recorded in Walmart’s joint venture’s books and records.

According to a 2023 article by corporate lawyers Andrew Reeves, Pamela Reddy, and Neil O’May for the global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright, the UK has also been cracking down on violations of its Bribery Act, which is even more stringent than the FCPA. Last year, gambling giant Entain announced that it had put aside £585 million to cover a potential settlement over alleged bribery offences regarding its former Turkish business, Sportingbet.

Last year, the UK arrested Romy Andrianarisoa, chief of staff to the President of Madagascar, for seeking a £225,000 bribe from Gemfields, a UK mining company, in exchange for licences in Madagascar. Former Nigerian oil minister Diezani Alison-Madueke has also been charged with receiving hundreds of millions of pounds in payoffs for contracts, and properties she is alleged to have purchased with them in the UK and US have been frozen.

Few believe these kinds of cases are a significant deterrent against global corruption. After all, members of drug cartels take the enormous risks they do because the lure of enormous wealth outweighs the risks of getting caught.

To function efficiently, economic institutions—just like our streets, our politics or our communities—need to be regulated by effectively enforced law. The absence of such enforcement is bound to lead to anarchy, and subsequently, to violence. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act isn’t some kind of naive exercise in morality—for all its limitations, it’s an important assertion of the principles that allow free-market economies to function.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Indicted by US, sentenced by the market. Damage to Adani this time will be deeper, longer lasting