Noida: The soft clatter of a librarian tapping at her keyboard and the silence of students hunched over their books in a Noida library is broken by the noise outside –– a young man is shouting expletives in Hindi into his phone. His meltdown only intensified, his face angrier even as he stood in the middle of a quiet street. There are many Noidas –– each enveloped by the contradictions that shape much of urban India.

A single street in this satellite town can play witness to disparate entities. Imposing glass office buildings, into which tumble a range of IT workers and affluent professionals, are framed by the stench of what Noida is infamous for: open drains. There are unassuming homes sandwiched together, and dreamy, palatial apartment buildings that scream luxury. From an industrial area, to Delhi’s simple satellite, and now a behemoth in its own right –– Noida has seemingly come into its own. There are internet subcultures dedicated to experiencing the city; which has grown into a dizzying mix of crime, ironic humour, and impressive malls. But 50 years on, it’s still waiting for public spaces and a culture that isn’t derived from Delhi or Gurgaon.

“We have houses. But we don’t have homes and we don’t have a city. We don’t have infrastructure that we can interact with,” said theatre professional MK Raina, who has lived in a Noida bungalow since 1992 –– when rents in Delhi began to skyrocket. “Minds should have come together, to give the city its authority, its ideas. We have RWAs, but beyond that, there’s nothing.”

But it isn’t all doom and gloom. Raina went on to add, for the most part, the essentials work. He’s always had ‘bijli-pani’: the twin banes that have come to shape Delhi life.

Before the gated communities and the imperious RWAs, there were a handful of well-intentioned individuals who strove to create a city.

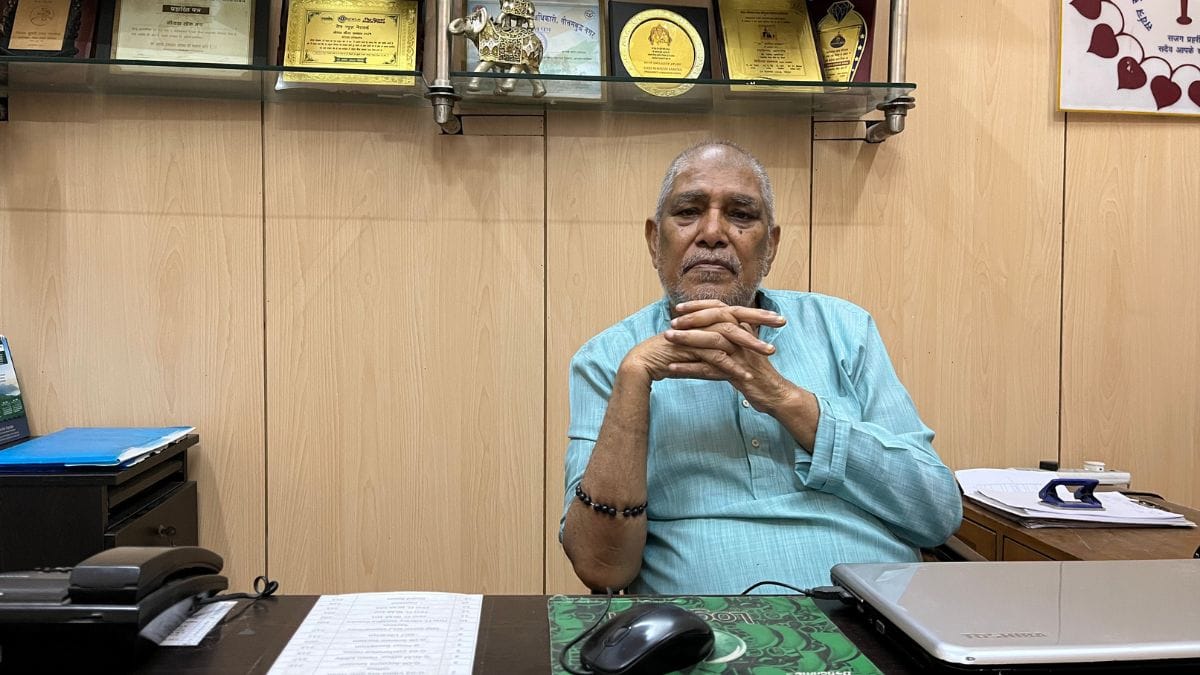

One of them was Mahesh Saxena, who founded the Noida Lok Manch in 1997. An almost-anachronistic good samaritan, he moved to Noida in the 1980s, following which he lobbied against corruption in the Noida bureaucracy by mobilising local people and holding dharnas. When that didn’t work, he moved to smaller pursuits: the public library, the crematorium, and bettering the city’s government hospital.

Saxena took charge of the Noida crematorium after the funeral of Kargil martyr Col. Vijayant Thapar and set up a permanent “how can I help you?” table outside the government hospital.

Over the years, things have changed.

Over the years, multiple Noidas have come up in Gautam Buddha Nagar. And some care less than others when it comes to doing their bit for the city. It’s high-rise vs gated sector vs village view.

“The people who live in the flats are unconcerned about our township. If we have 25 lakh people living in Noida today, only a few care about society,” said 77-year-old Saxena. “We take out surveys, asking people what their problems are. But 50 years later, they’re not being settled.”

According to him, the stubborn problems in question are untreated sewage, a paucity of septic tanks, water pollution and the existence of slums.

“Is the only measure of vikas buildings?” he asked.

Originally from Uttar Pradesh’s Bundelkhand, he remembers better times. He claimed to be instrumental in the removal of IAS officer Neera Yadav, the UP chief secretary who was sentenced to two years in jail due to her involvement in the Noida land allotment scam, which took place over 2 years, from 1993 to 1995. At the time, Yadav was CEO of the Noida authority.

“It was different. The media was also honest then. She [Yadav] once asked me: what did I ever do to you,” said Saxena mournfully.

It was easier to mobilise people, to get them to care about localised, city-related issues.

But he manages to keep busy. On average, his public library located in Sector 14, one of the city’s early sectors, sees over 15 “housewives and senior citizens” who borrow and return books. They borrow history books, fiction tomes, and the occasional self-help. They’re all from the neighbourhood.

According to library-in-charge Vibha Kaul, there is no other such space in the city.

Also read: At 50, Noida doesn’t know what it wants to be—cosmopolitan city or industrial utopia

A strange cocktail

The city and its people provide comedians and social media creators with an abundance of content. A simple drive around town gave writer, filmmaker and podcaster Anurag Minus Verma a lot to work with –– alcoholics and an Italian mall.

“Noida is full of people who live like they’re being watched by a hidden camera, by god, or by their invisible enemies. Everything is a performance,” he said. “Even stepping out of their Thar feels, in their minds, like an audition for Bigg Boss.”

He also added that getting on to Bigg Boss is a primary ambition for several local Noida creators. In this newly mown metropolis, the lines between the urban and the rural are obscured.

You see a strange cocktail: farmland converted into real estate brochures, local boys becoming landlords and gym owners, sons of farmers now selling protein powders on Instagram

Anurag Minus Verma, filmmaker and podcaster

“You see a strange cocktail: farmland converted into real estate brochures, local boys becoming landlords and gym owners, sons of farmers now selling protein powders on Instagram,” he said. “The children of those who sold the land are now trying to imitate the culture of those who sit inside the glass towers built on it.”

But their only real stage, according to Verma, are the streets — where they flaunt their vehicles, an extension of themselves. Social media is filled with reels of young men devoted to their Thars and a of litany complaints against the drivers.

“The road is where everyone is negotiating what prestige means, and hence every single vehicle is proudly displaying their caste name, and these days even their Instagram and YouTube Ids,” he said. “Caste and follower accounts are their idea of cultural legitimacy.”

In one of his videos, comedian Shubham Gaur reverses the Noida stereotype. Once again, he doesn’t have to go too far to subvert the cultural norms that dictate Noida. All he does is adopt the identity of a man who is polite. He doesn’t fight over parking, is civil to a security guard and doesn’t lose his temper over a pet dog. This docility is supposedly antithetical to the Noida citizenry –– who are irked by the daily, the mundane issues that are part and parcel of urban life.

Also read: 6 years, 400 trials, and a breakthrough—how Kashmir gave India its first gene-edited sheep

In shadow of crime

Noida is not known for its quietly burgeoning library movement. Instead, for certain young people, the city’s been constructed by the sensational crimes that, at one point, were inextricable from Noida. The 2000s saw both the Nithari killings –– a grizzly set of murders committed by businessman Moninder Singh Pandher and his domestic worker — and the ‘double murders’ of Aarushi Talwar and Hemraj Banjade.

True crime podcasters Aryaan Misra and Aishwarya Singh were in school at the time.

“Both cases remain so vivid. But it’s not like we were ever directly in contact [with either case],” said Aishwarya. The duo hosts The Desi Crime Podcast, arguably India’s biggest true crime offering. “But there were connections. They were some of the first cases we covered.”

Aishwarya recalled playing a basketball match at Talwar’s school, while Misra remembers attending a science competition at the same school. While he is now based out of Mumbai, his aunt used to live next to the Pandher house.

“Each time we drove past, my mother used to unfurl the fact of the murders to us –– as if it was the first time,” laughed Misra.

Misra and Singh studied at the Shiv Nadar School in Noida, and what they experienced was “a constant juxtaposition.”

“Villages are woven into the fabric of the city. My mother is a lawyer, and one of the courts she practices in is the Noida district court. You’d think that the cases which reach the court [like dowry cases] belong in the village,” he said.

Desi crime has a devoted listenership, many of whom are driven by Misra and Singh’s style of storytelling and world-building. However, with cases based in Noida, they’re able to infuse cases with what they described as “personal flavour.” And since the stories themselves are embedded in public memory, new listeners also tune in.

One episode, which covers the 2023 murder of a Shiv Nadar University student who was killed by Anuj Singh, an obsessive male classmate has the duo discussing how intimately they know the scene.

“We’ve had ties to the university. This is all very close to home –– it characterised our adolescence,” Misra said somberly in the episode.

They revisited the infamous Aarushi Talwar murder as well as the Nithari killings early on. Despite the fact that years had passed, and that the various shades of information were more or less in the public domain, the episodes did well. The Aarushi episode, in particular, according to Singh, “received an overwhelming response.”

In 2023, 50 murders, 453 crimes against women and 1,098 vehicle thefts were registered in Noida. All three categories saw lower incidence than in 2022 and 2021.

“I don’t think they [episodes based out of Noida] capture the listener more than those which aren’t. But with the SNU murder case and the Nithari case, we were able to solicit interviews with people connected to the case –– friends, witnesses,” explained Misra.

For both true crime aficionados, images associated with UP –– the badlands, Mirzapur and the “crime belt –– have seeped into how they view their city.

But, “it’s not just a perception when you see crimes happen. The SNU murder used a locally made gun. When such incidents happen, they reinforce the idea of Noida as this mob land,” said Misra.

In 2023, 50 murders, 453 crimes against women and 1,098 vehicle thefts were registered in Noida. All three categories saw lower incidence than in 2022 and 2021.

Comedian Shubham Gaur minces no words when he explains the interplay of the cityscape and crime. In one of his reels, he plays a Noida man with a single indulgence. Everything is cheap, inexpensive. His clothes, shoes, watch. The only thing he spends on is his gun.

Even for the writer of Mirzapur, the Netflix show which wrested a crime-ridden UP into the spotlight, Noida has emerged as fertile ground for storytelling. CA Tribhuvan Misra, also written by Mirzapur’s Puneet Krishna, put Noida front and centre — giving the city its own Netflix backdrop.

“There is a certain kind of perception. Ghaziabad, Noida, Meerut have associations with the sensational,” said Krisha. “And perception does play a role when you’re writing about a certain kind of town.”

Yet, when it came to CA Tribhuvan Misra, which narrates the tale of the protagonist’s side-hustle as a sex-worker, Krishna chose Noida for its contradictions –– its smaller town character masked under the facade of a big city.

“I had 2-3 specific qualities in mind. I didn’t want a very big town — where gangs can freely roam around,” he said. “I wanted a melting pot, a good-looking, well-developed society.”

He also wanted to experiment with Noida’s identity, by allowing a story of “sexual openness” to unfold in a city that isn’t known for being open minded.

Another Netflix series, Sector 36, is “loosely-based” on the Nithari killings, and has certain elements of the now ritzy city. Contrary to actual events, a boy attending an elite school is abducted. A shell-shocked woman in a juicy tracksuit looks on.

“We’re only three officials for a population of 150,000 people! Don’t we deserve time off?,” says the investigating officer.

Also read: Rs 6,000-cr stadium, weekly meetings, 2030 CWG pitch—Ahmedabad’s Olympic plan speeds up

The infra flex

Noida’s infrastructure boom is known for its fleet of malls. While they arrived on the scene years after Delhi and Gurgaon’s plush shopping centres, and post the mall-craze –– they’re now firmly seated in the city’s popular imagination, and are essential to its identity.

DLF’s Mall of India boasts of being Noida’s “biggest mall.” On a Friday afternoon, it plays host to a consistent stream of mall-goers. But they’re no monolith. There’s a diversity of people. Young men congregate outside a Miniso x Harry Potter pop-up, taking photographs and finding their perfect selfie angle with the Harry Potter logo as their background.

There are those who’ve come to get a job done, and a sizable chunk who appear to simply be soaking in the mall: the bright lights, the chill of the AC, and the gleaming stores.

Nikhil Yadav, a concierge at the mall, is wearing a neat blue suit. Currently pursuing his B-Com at Delhi University, he was in search of a side gig. With dreams of starting his own business, Yadav enjoys the highfalutin people he gets to meet and the access they could potentially bring.

“It’s not bad. You also get to visit stores, learn about their sales,” he said. “The thing is, that in Noida, if you have a business idea –– you can get it implemented depending on who you know. But you need the idea first,” he said, referring to the batch of tech companies and various commercial entities that have made a home in the city.

He rattled off all that the mall had to offer. The temperature is fixed at 22 degrees. The 4-wheeler parking can hold 1,696 vehicles. There are 81 escalators. The mall is set on an area of 20 lakh square feet. There are 304 permanent stores and 75 kiosks. It saw the arrival of high-street stores like H&M and Uniqlo before Gurgaon.

It’s not just Noida residents who frequent the mall. For those living in East Delhi, the Noida malls have become an obvious choice owing to proximity. Earlier, their primary entertainment destination was Central Delhi’s Connaught Place. But now, they shuttle between the two.

Noida dwellers appear to be rather thrilled, and take pride in the breed of infrastructure their city offers.

“One of my favourite spots is Colocal,” said Gauri Khanna, a 27-year-old lawyer. “It has a calm, open vibe.”

Colocal’s original outlet is in Chhatarpur’s Dhan Mill. The chocolaterie also has a cafe in Khan Market –– another trendy, expensive address.

“There has long been a sense of superiority that many Delhi residents have harboured towards Noida,” Khanna said. “But it’s important to acknowledge reality.”

She pointed squarely in the direction of real-estate prices. Even those living in “well-established” Delhi neighbourhoods might find it “difficult to buy a good 3 BHK in Noida.”

An architect with Discover Patterns, which has worked across NCR, spelled out part of the difference.

“Business people choose Noida over Gurgaon for three things: prices are lower [than Gurgaon], sectors are gated and they don’t have to invest in stilled parking,” he said.

In Gurugram, homeowners are required to dedicate one floor to stilled parking. In Noida, they can build and build.

Also read: Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir are branded as kafirs, boycotted, spat at. They hide, pass as Sunnis

The missing intellectual space

In the 1990s, theatre maker MK Raina made an attempt to imbue Noida with some culture. After a phone call from the then-chairman of the Noida authority, he suggested the formation of an “arts council” –– a space where writers and painters could congregate. But it never took off.

He wanted to hold theatre workshops. But auditoriums in Noida charged between Rs 25,000 and Rs 30,000 for a day’s work. Raina and a group of illustrious residents also broached the idea of a Noida International Centre –– built on the lines of Delhi’s India International Center. It was due to open in 2015. But once the plan was set in motion, the Noida authority began to insist that it be headed by them.

“Say I wanted Salman Rushdie to come, would he come because a bureaucrat invited him? There needed to be eminent leading lights of the city,” said Raina.

To keep up momentum, he holds workshops in the ‘aangan’ of his home –– casual get-togethers which consist mostly of young people and Raina making chai.

His biggest grouse is that there are no spaces for young people to freely chat, luxuriate in conversation.

What Noida does have, however, is the Dalit Prerna Sthal. Built by the former UP Chief Minister, it was seen as part of her bid to construct real-time monuments. Less than a kilometre away from the Mall of India, it consists of elephants crowned by manicured palm trees, gigantic tomb like structures and a Rs. 25 entry fee.

For the most part, there are only groups of men who skulk around, finding shade inside the monument. A young woman, who has clearly dressed up for the occasion, walks around with her child and husband. She just moved to Noida and this is her family’s first visit to the park.

“My husband works a private job,” she grinned. “We love Noida –– bilkul sahi hai.”

This article is part of a series called ‘Noida@50’. Read all articles here

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)

A loose compilation of unrelated observations about Noida masquerading as an ”article”. I lived in Noida from 2009-2020 and saw the region experiencing a growth spurt. I’m quite familiar with what’s on offer but these were/are true about other places like Gurugram, Faridabad too. What you have sorely missed are some of the huge advantages – planned sectors, (relatively) better roads than other two suburbs, tonnes of greenery -really good parks and trees on traffic islands and medians. A key negative is there is no defined city center that any true city should have where citizens can go without a commercial transaction – but then gurgaon and faridabad don’t have it either. What noida does have is relatively better connectivity to central delhi such as Connaught Place and India gate by road and metro and that gets you to all the art, culture and even more greenery very quickly. This is not journalism, it is just saying something for the sake of saying it.

Well-written article except that “Stilt” Parking has been referred to as “Stilled” Parking multiple times. STILT parking is where the ground floor is left empty for parking with just free-standing stilt columns supporting the structure above. My observation from the last 20 years is that solid-waste (garbage) management has deteriorated all over Noida & it is much more difficult now for ordinary citizens to deal with bureaucracy at the NOIDA authority by themselves without an “agent”. Compared to Delhi, there is a definite lack of FREE public spaces in Noida (and in Gurgaon/other suburbs) like parks & gardens & cultural institutions/ galleries/ museums etc. available to citizens of all economic classes. Crime across the entire Delhi-NCR region including Delhi, Gurgaon, Noida, Ghaziabad, Faridabad etc. remains uniformly high. Electricity & water issues in Delhi improved significantly in the early 2000’s and has remained at about the same level across the entire Delhi-NCR region since then. Delhi & Noida always had better urban planning than Gurgaon that was “developed” in a rapid uncontrolled way by private builders and therefore has no proper sewage system & does have huge issues with stormwater management/flooding.

Absolute nonsense. Sir, Please tell me if any of these problems don’t exist in Delhi itself, or in Faridabad or Gurgaon. In fact, all these exists ten times in Delhi. I feel 80 percent of Delhi lives in unauthorised regularised colonies, not worth human living. 100 percent or atleast 80 covered area and FAR above 5. Sir, I request the authors to please visit colonies in Delhi that are outside DDA and which have come up in the last 50 years. Noida s problem are smaller in scale than Delhi colonies.